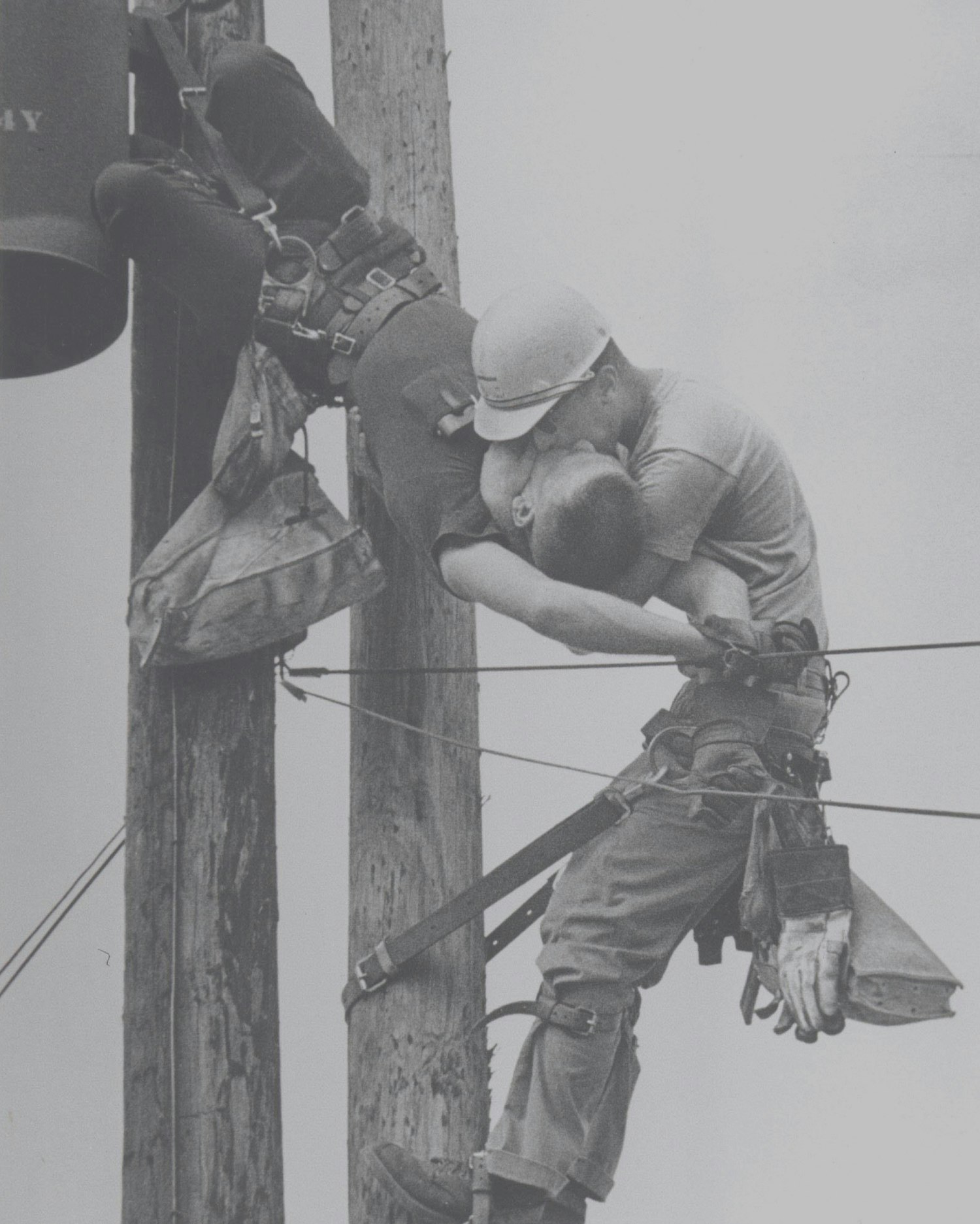

For far too long, major public works have been presumed to be inevitable and value neutral. Academics, practitioners, and users, claimed that infrastructures become visible only when they crumble and fail. In other words, infrastructures are meant to be invisible. We push against this long-held assumption and argue that infrastructures are not inherently invisible, but they are made to be invisible. And it is not just infrastructures as objects that we learn to un-see, but infrastructures as people, as maintainers, as caregivers, who are made to disappear into the background.

Design has a role in this, for design is a negotiation, and design can make larger abstractions like social policies and technological networks more usable–and sometimes more culturally visible. So there is something very positive about a new appreciation and participation, not only in design futures or policy debates, but also then in more conscientious everyday use of infrastructures. Here cultural values do start to shift, whether around food and water, energy, mobility, broadband, and not only around so much hard infrastructure-building on the agenda, but also with concern for the soft infrastructures that make those more resilient, knowable, and equitable.

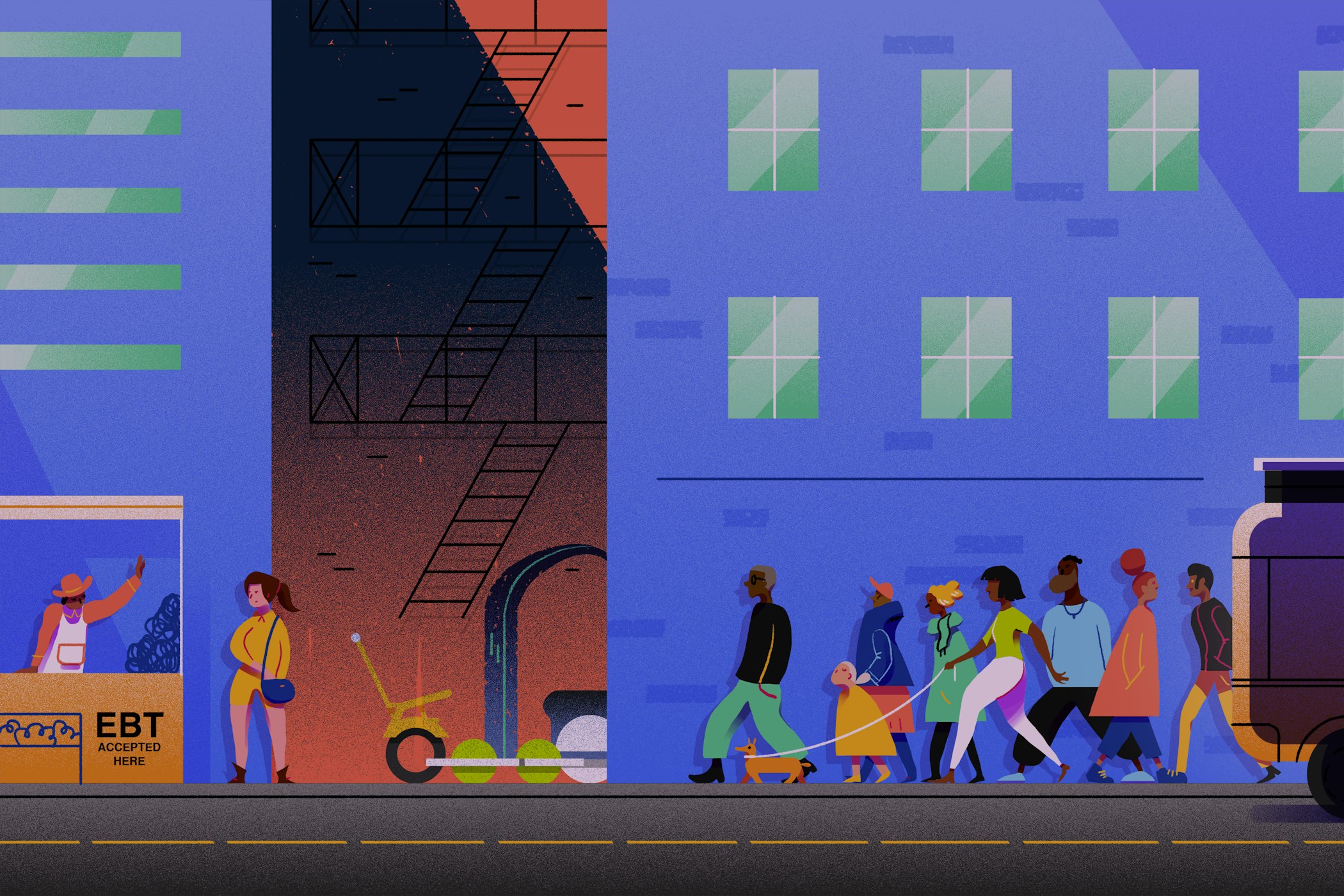

The question of whose infrastructures does seem vital. Without it, too many projects serve some and not others. Too few systems imposed from afar match very well with local social practices on the ground, or as an engineer or policy analyst might put it, in the wild. Alas seldom can the big disinterested money of governments or transnational corporations understand and uphold the more enactive kinds of knowledge that reside in places. Seldom does the galaxy of local advocacy groups and nonprofit/nongovernmental organizations have enough clout to uphold nonfiscal values of social practices. But if that sounds like the same old urban politics, (think Jane Jacobs vs Robert Moses), it is not. Amplified by media, driven by the planet, and with a vastly more diverse set of players, the perennial work of getting infrastructures right has new dimensions, new opportunities, and new design challenges. (Not just incidentally has the college launched an urban technology degree to probe some such prospects.)

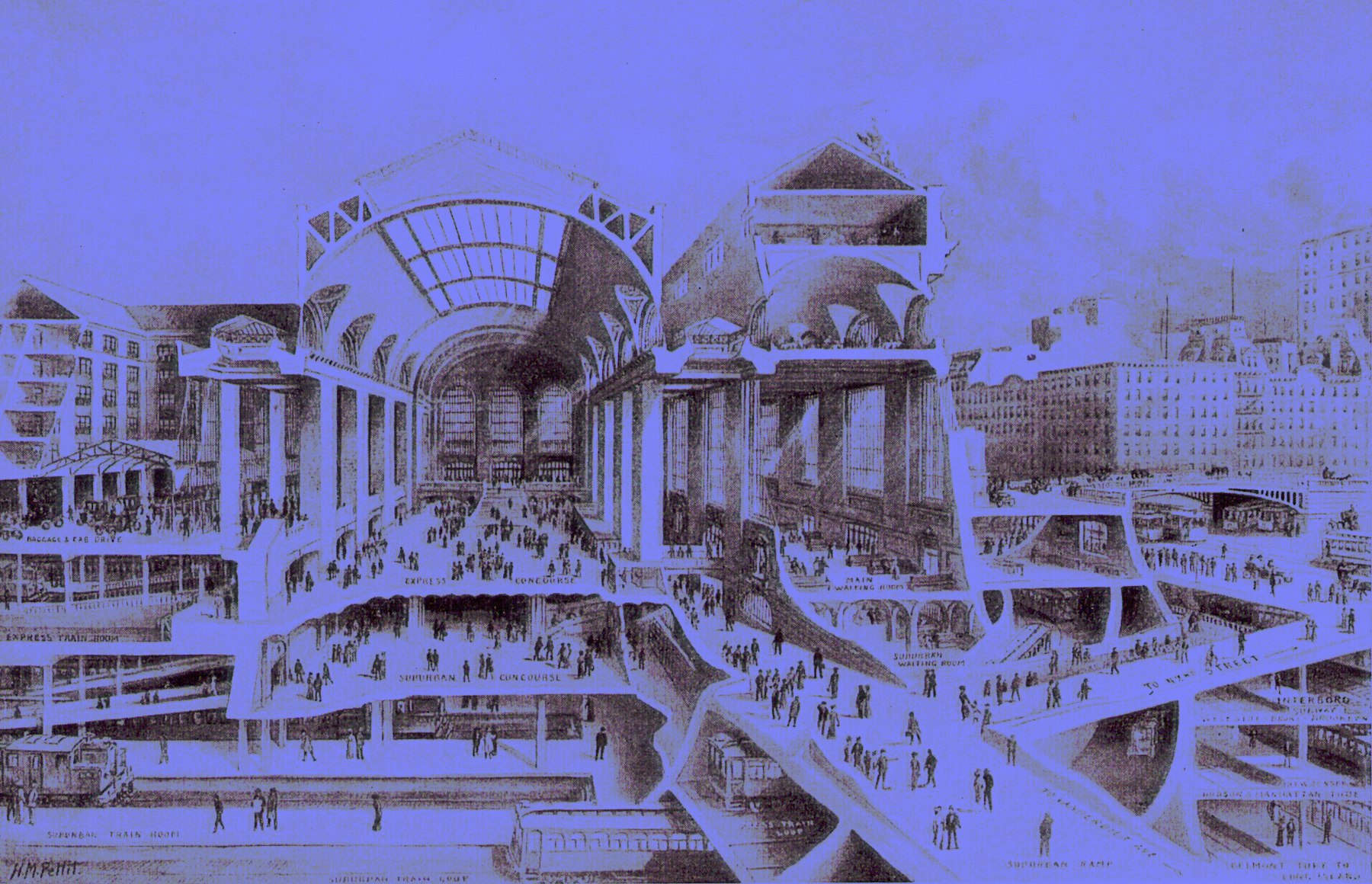

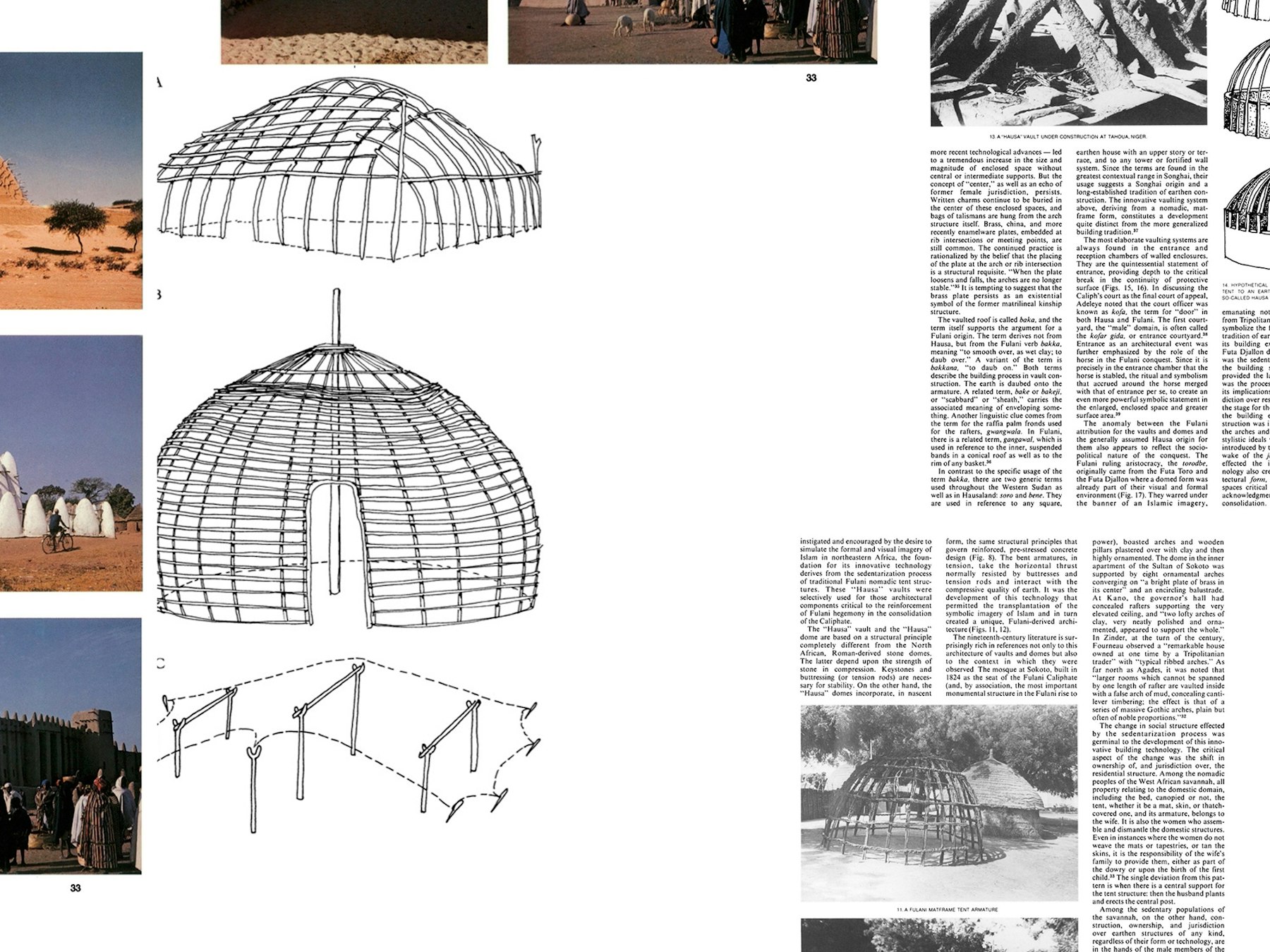

Infrastructure is an obviously pressing contemporary issue, but also a historical one. As a system that organizes, builds, governs, and sustains everyday life, infrastructure has long been wrapped up in politics of imperialism, settler colonialism, and racial capitalism. In the 20th century, hard infrastructures were at the center of the New Deal and the military industrial complex alike. The interstate highways were instigated and later named for a wartime general turned president. The internet began as a defense solution. In the 19th century, soft infrastructures of work organized slavery and indentured labor, and everyday uses of urban infrastructures like water and transit paved the way for Jim Crow and segregation. What any of this means today may not be what it meant back then. So it is worth reciting in a somewhat longer global historic voice, how back then (and somehow all the more questionably today) the technological advantages of the industrialized north were too easily mistaken for cultural advantages. It is worth repeating that technological change was (and somehow sometimes still is) considered obvious and inevitable. Yet as social historians of technology have so well explained, the adaptive path was seldom linear. Even for infrastructures so incontestably advantageous as electricity, different cultures built and operated it differently. For of course electric power was also political power.

The question “whose infrastructures?” now invites fresh critique. Whereas new deal projects came from the left, today privatization comes from the right. Where in the 20th century what was salient was how many more people could connect, by now what stands out is those still somehow left behind. Where technologies have disappeared into normalcy globally, their originators no longer control quite so much about them. Today when so many technologies have global reach, if nowhere near not universal access, the earlier lead of the global north or anglo-america industrialization no longer constitutes as much advantage, cannot remain a template, and indeed has worldview shifts of its own at home. Here in North America, the scope of this journal, and certainly here in this college, this cultural value shift shapes up mainly around the egalitarian city.

Scholars of historical and contemporary infrastructures have engaged with Indigenous land defenders, Black Lives Matter organizers, abolitionists, and other activists to document and challenge so many normative frameworks. They have pushed to imagine alternative infrastructures for collective and decolonial forms of being. However vital all this seems for the global south and the future of the planet, it also plays out in the American city. Such work invites positive engagement in a cleaner, greener, more local, and more inclusive set of city services–and also citizenship.

What does the discipline of architecture bring to this conversation? How can architects’ insights into locality, scale, and embodiment bring more kinds of participants into the work ahead? And, in turn, how might a clear focus on infrastructure transform the social, cultural, and political commitments of the discipline itself? The Gradient journal is especially well suited to bring this conversation to the forefront. Architects, who balance a view to history and a view to contemporary opportunities, are best positioned to advance this rapidly expanding conversation. They are able to move beyond practical questions of resource efficiencies and environmental resilience, and to provoke others to imagine what life could be like. Grappling with infrastructural inequities requires utopian—and even architectural—thinking. And we can see that the multiplicity of forms, shapes, and effects of infrastructure requires that we think about these vital systems in plural—hence the special emphasis on infrastructures.

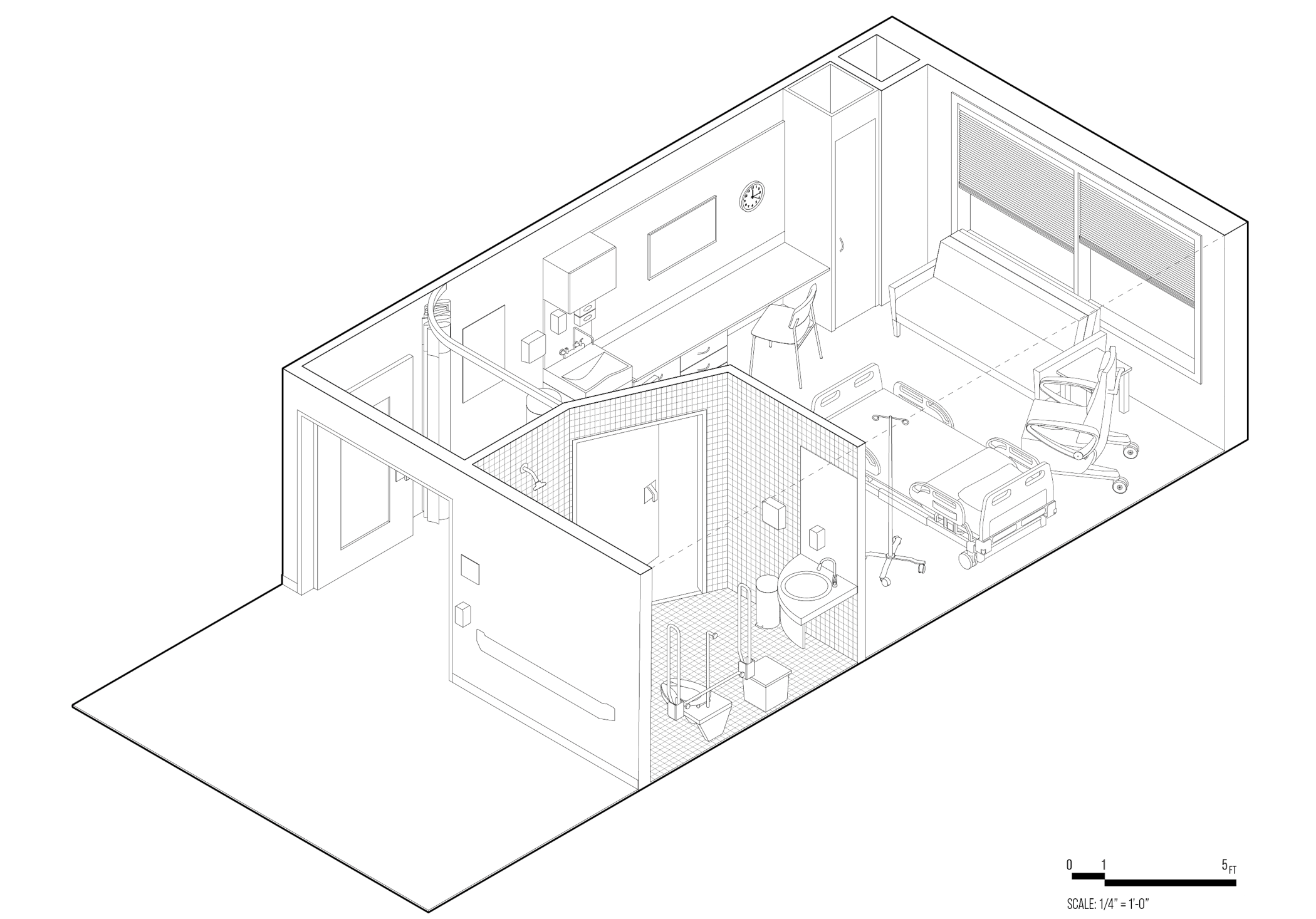

Architects are crucial interlocutors in conversations about infrastructures because they work at a multiscalar level, balancing both global systems approaches and small, site-specific projects. We might refer to this as capital-I Infrastructures and small-i infrastructures. They exist in a unique and complicated relationship with one another, at times running parallel, in competition or even in opposition to one another. We must study I and i together because through this relationship we can better understand power. We can see how small infrastructures like local agricultural cooperatives can subvert and challenge large infrastructural frameworks of industrial agriculture and even big tech. Studying infrastructural power also requires that we experiment with new research methodologies, embracing ethnographies in addition to more conventional ways of mapping the geographies of technological networks.