The following text is an informal conversation, condensed and collated from a series of discussions between McLain Clutter (Chair of Architecture at Taubman College), Tsz Yan Ng (Associate Professor of Architecture and co-editor of this year’s Gradient feed Inflections), and Rebecca Smith (PhD candidate and Gradient editorial team).

- Rebecca Smith (RS)

-

So we’ve been talking informally about themes that come up across this year’s feed, and we thought a good starting point might be to ask, what do we mean when we use the word “technology”? How do we use that term and what are its more nuanced connotations? Maybe we can start with you, Tsz Yan: What are your thoughts, and how do you understand the role of technology within the feed, or across some of the work that the ACDCC group is doing?

- Tsz Yan Ng (TN)

-

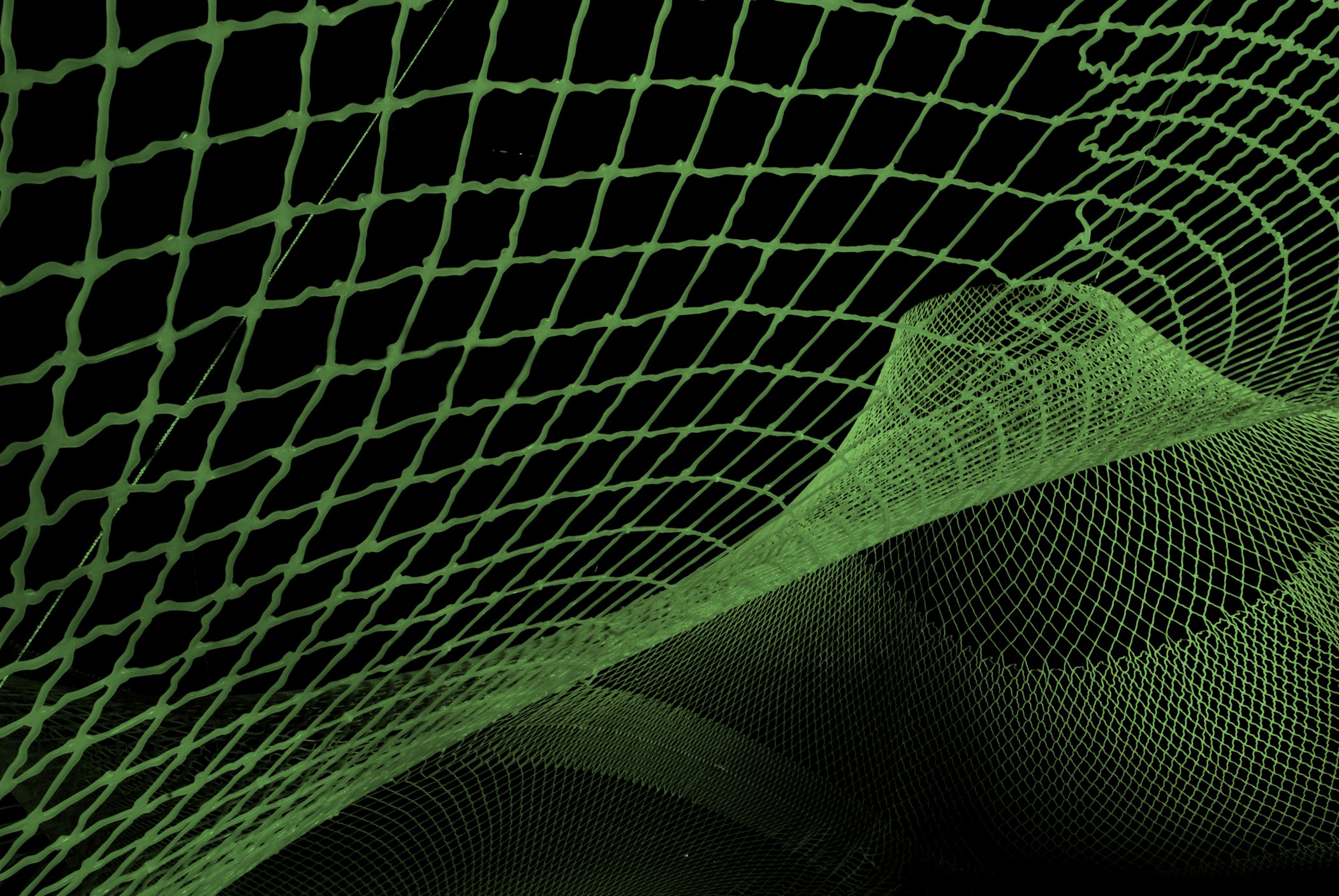

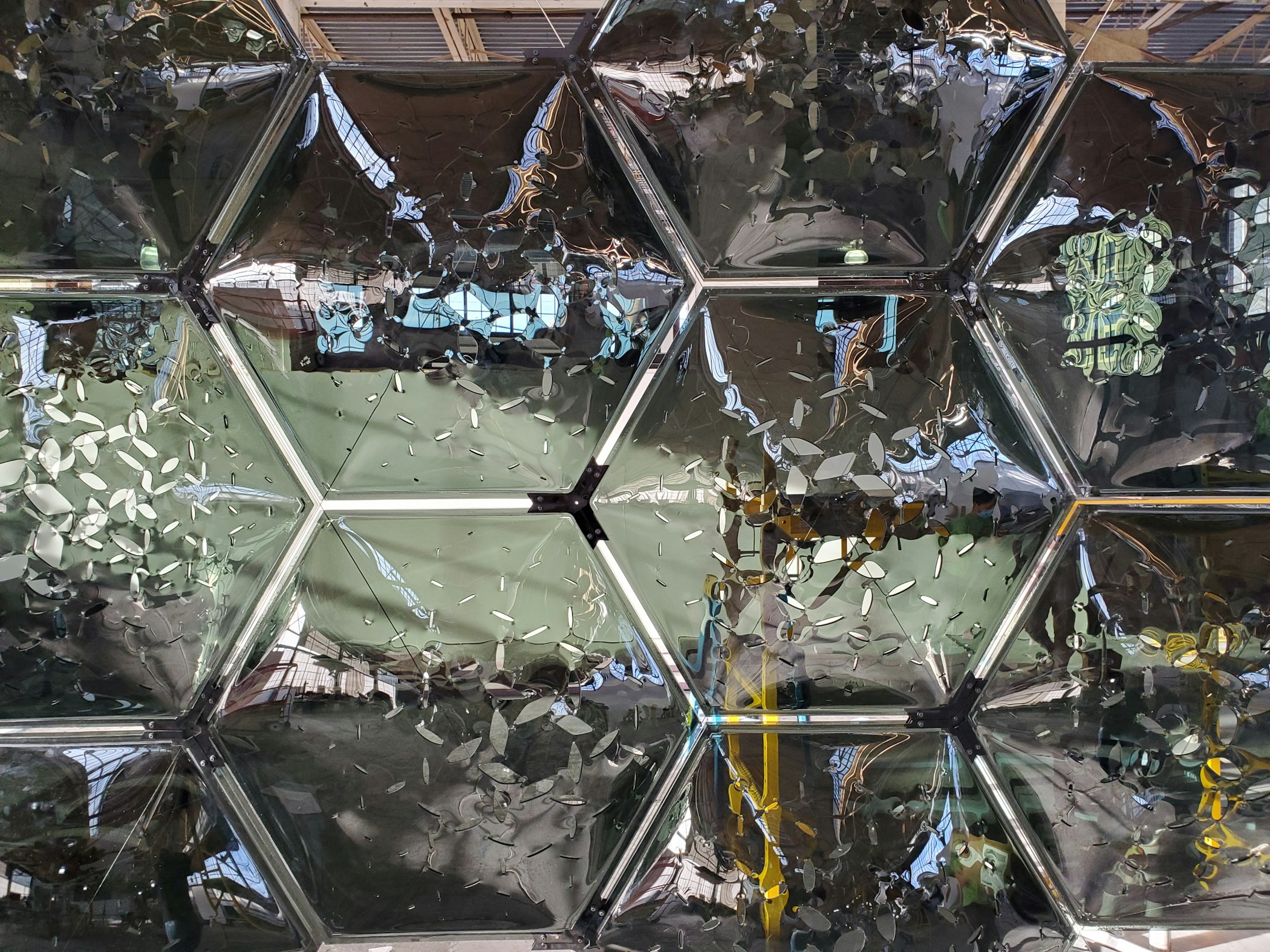

The use of the term for the ACDCC group is about how new manufacturing technologies are enabling unique forms of crafting and ways of building that previously were not possible—whether it's cost or labor prohibitive, or addressing climate-based imperatives. (Figs. 1–3) When I think of the term technology, I think of tools, software, and techniques that produce architecture outside of conventional means. For instance, what opportunities are afforded by such-and-such technology and why? I think that is how the term is typically understood, or perhaps mostly used by the group. Or more broadly in architecture.

However, I have a slightly different definition of the term technology. For instance, this technology is for this, and it does this only. I don’t see it as exclusive to a singular purpose. I see technology as transitive. You can change it for other kinds of purposes and applications. It’s not fixed. There are creative uses for technology. Take, for example, a pen: it’s a writing instrument, but I could also stab someone with it. Don’t mean to be so graphic to make a point! But this is ultimately what I find fascinating about technology: how it’s appropriated, how it shifts with our current thinking, and our priorities. The most creative uses are when it’s far from our usual association, deployed in a completely different context. Even processes can be a technology, like cake piping, it’s really not that different than concrete 3D printing—some material is extruded out of a nozzle, the nozzle can be designed to shape the deposition, and the pressure you put in squeezing the material out controls the flow of the material through the nozzle. Granted, I’m grossly simplifying concrete 3D printing. It’s much more complicated than that. But conceptually, it’s similar, just at a different scale, and what gets extruded has to do more with structural capacity: how high can I build, etc. That’s how I think of technology.

But I think in general, in terms of the ACDCC group, it’s really situated in the production of building and making or imagining. For instance, software as a form of technology is used in that sense: the framework of a particular technology informs a particular mode of making and design.

[Fig. 2] Robotic extrusion of thermoplastic elastomer (TPE) on 4×8 foot thermally controlled aluminum surface. Infudibuliforms, by Kathy Velikov, Geoffrey Thün, and Wes McGee, 2016.

- McLain Clutter (MC)

-

I think the last time we talked about this, I experienced a moment of paralysis when asked to define technology, and I guess that’s because I understand the term pretty broadly. I think technology encompasses almost everything in human creation that has been applied to instrumental goals. That would include everything from tools like pen and paper, to the kinds of advanced computation and fabrication research that members of the ACDCC conduct, to abstract devices like grids—to summon Bernard Siegert’s writing on that topic. I think this kind of broad understanding can make the business of definitions difficult, and maybe it threatens to become too expansive. If everything is a technology, then the term starts to lose its usefulness.

But I’m also very skeptical of definitions of technology that are narrow. Too often technology is closely tied to a cult or fetishization of the “new.” So, when we refer to technology, or research in technology, I think we’re often tacitly endorsing the idea that newness is inherently good, and “innovation” is a valuable end in its own right. When we adopt that kind of thinking in an academic context, I worry that we align ourselves too closely with a free market mentality. For me, this also aligns with the neoliberal mindset that has colonized 21st century academia, where expansion and growth, ala the free market, is also accepted as an unqualified “good.” In these scenarios, we stop asking critical questions about the ideologies or social and political implications embedded in new technologies, because we’ve uncritically accepted that newness equals progress. That worries me.

Assuming that technology is always about the new also allows us to think that the old technology that’s all around us all the time is natural, rather than naturalized. In fact, that old technology is the result of historical processes and decisions.

[Fig. 3] Custom-calibrated slumped glass with geometric modification at various scales to influence a range of acoustic behaviors: reflective, diffusive, and absorptive. Long Range by Catie Newell, Wes McGee, and Zackery Belanger, 2022.

- RS

-

McLain, I appreciate how you're naming a gut-level aversion to innovation, both as a concept and also as a kind of brand or a tag. My own aversion to the term comes from how it assumes a kind of blank slate, and also a judgement: that the knowledge and conditions produced through innovation will be inherently better than whatever has been in existence before.

If “innovation” is only interested in what can be monetized, it also marginalizes or renders invisible anything that does not fit into this system of valuation.

-

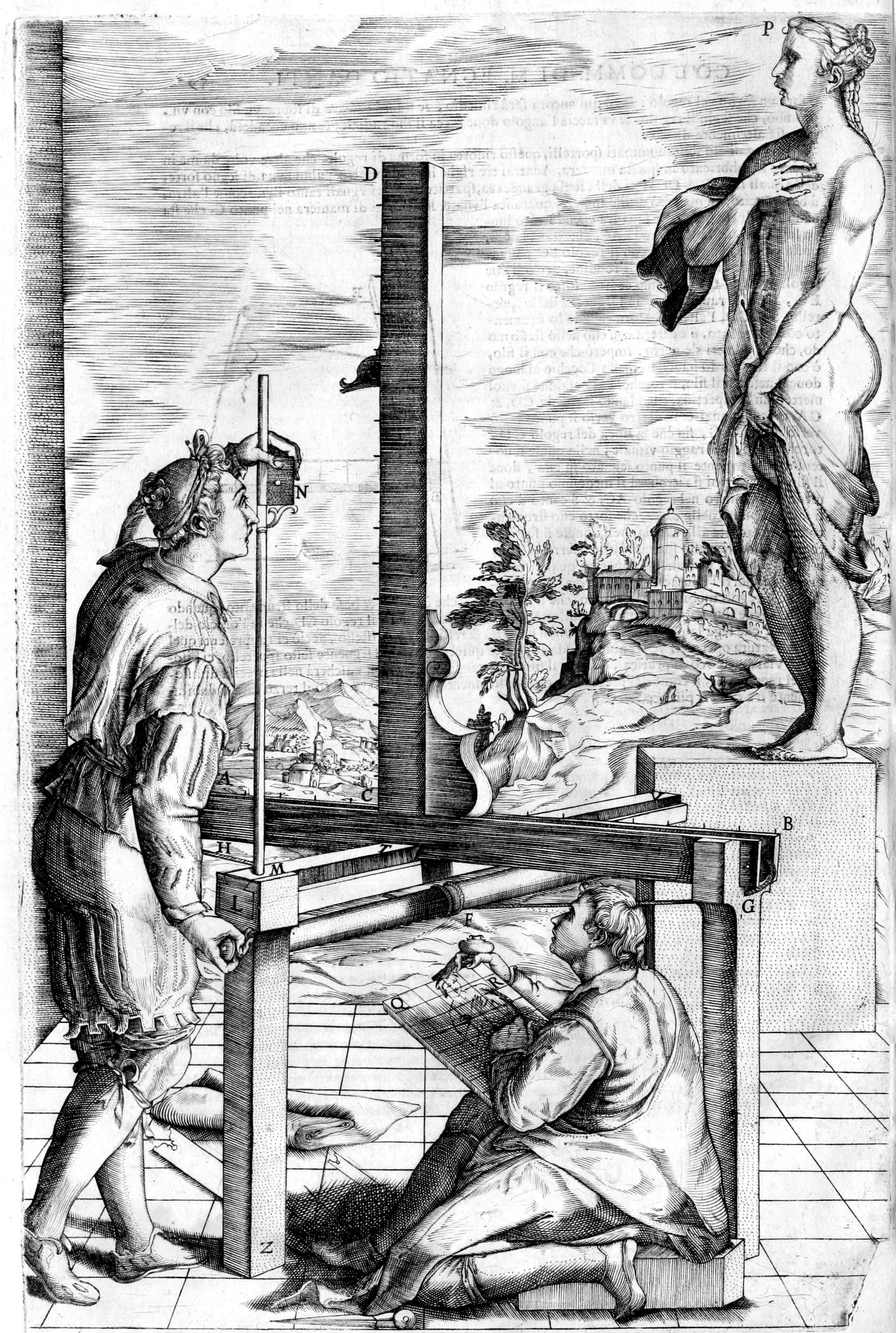

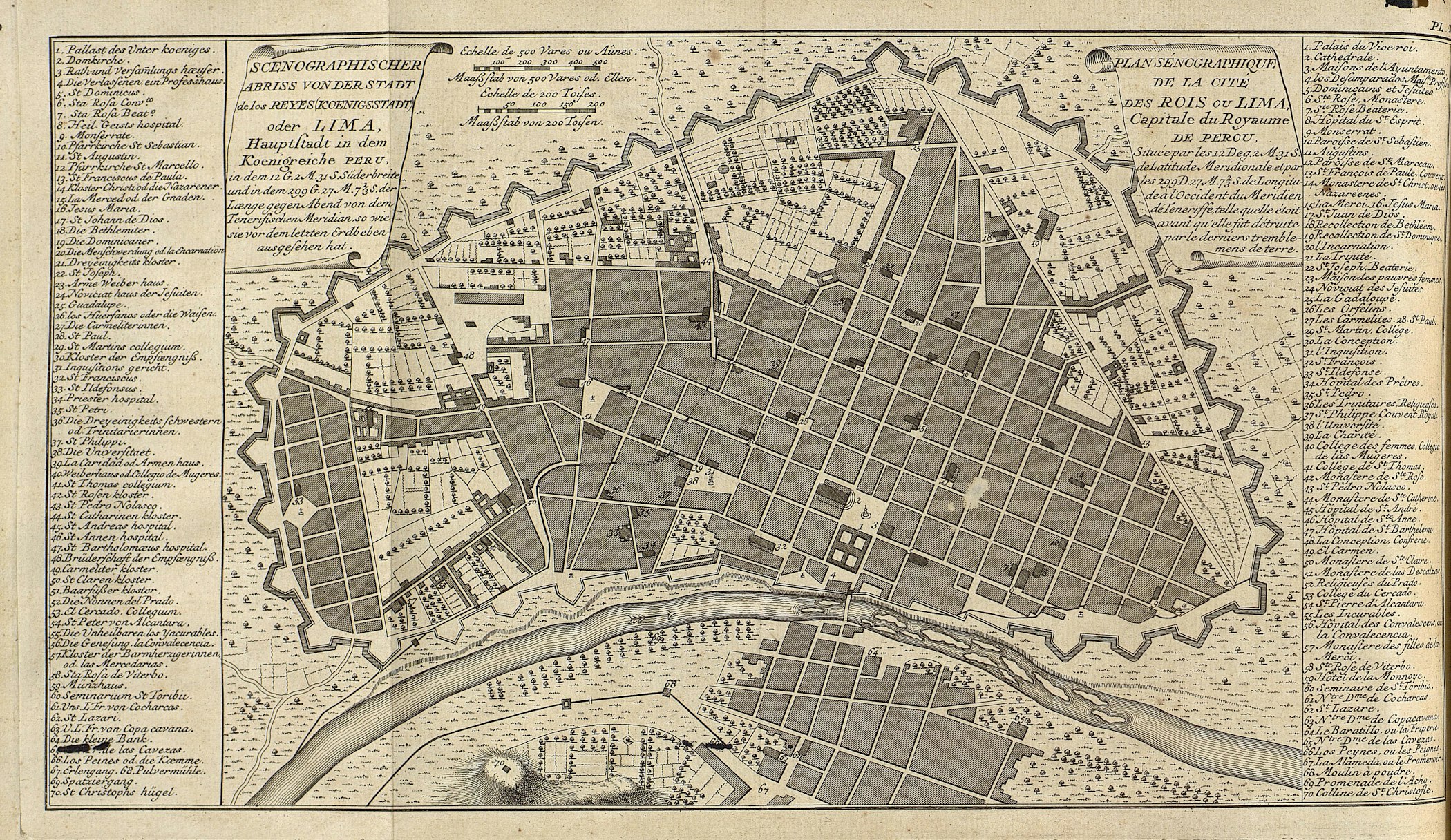

You mentioned the grid as discussed by Stiegert, which I think is a clear example: it gets at the erasure inherent in ideas of “innovation,” the assumption there was nothing there before, and also the potential violence and harm that comes from “innovation”, as, in Stiegert’s telling, through the grid as a form of technology as related to colonialism [Figs. 4 & 5]. And this is not just limited to material and spatial practices, but the way the grid became foundational to a certain epistemology or worldview, one tied inherently to capitalism, white supremacy, and ecological devastation. So I’m not saying that innovation in technology necessarily has all of those consequences, but coming back to the initial question, I think we're both, perhaps, emphasizing a certain way of talking about technology: the “X-as-technology” framing, which I find really helpful. To draw from STS (Science, Technology & Society) framings, what is the work the technology does in the world?

- MC

-

I think part of what you’re suggesting is that a better question than “what is technology” or “is X a technology” would be to ask “what would it mean to evaluate X as technology?” The latter question is less definitive and more methodological.

- RS

-

It becomes what is the technology doing, and/or what is it enabling. This agency, or agencies, then become the objects of analysis, which I think is useful.

- MC

-

Agreed. At the same time, I’m aware that the skepticism to solutionist framings of technology or terms like “innovation” that you and I have, Rebecca, are a non-starter in some areas of research represented in the ACDCC cohort. For example, in your line of research, Tsz Yan, innovation talk and solutionist rhetoric seems de rigueur, just to maintain the funding required to advance your work.

- TN

-

I should clarify that just because someone may proclaim what they are doing is ‘innovative,’ it actually may not be and in no way, by just using the term, does it guarantee funding. I just submitted a grant and I searched for the term innovation in the document. It’s mentioned twice, but only in the broader impact section of the writing. So I think there’s a perception that technology-related research is purely innovation for newness sake, that something new means better. I think a lot of people are critical of that, especially reviewers for these grants. If it’s not broken, it does not need to be fixed. There are limited resources in this world, this part is a clear reality at the moment, whether we’re talking about monetary resources or natural resources. Unfortunately though, there are a lot of things that are broken in our society and many of those issues need urgent attention, like the housing crisis—perhaps because our attention was on one aspect but not realizing the ramification it might have for specific groups of individuals. I think innovation in that sense could be a corrective measure.

[Fig. 4] Perspective machine, from Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola's Due Regole della Prospectiva Pratica, 1611. (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/gri.ark:/13960/t8w95tn9v?urlappend=%3Bseq=66)

[Fig. 5] PI.XXII, Plan sénographique de la cite des Rois ou Lima, 1750, by Juan, Jorge. Image from Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%22Pl._XXII%22.Plan_s%C3%A9nographique_de_la_cite_des_Rois_ou_Lima(19864999310).jpg)

-

But I want to go back to the way that you’re describing your allergy towards that term. I think it has to do with how that term has been appropriated and used in popular culture. It’s broad, what you described as the need for the new, there’s this kind of neoliberal association with money and power—‘tech industry.’ That’s a broad definition that’s now associated with a particular group or sector, instrumentalized for raising startup funds or something to that effect. If we are having a kind of framework by which to evaluate that term, then I think it would be very different, not just for technology but also for innovation. If we frame how those terms are used and in which context, I think that would be very different.

And in fact, the one thing that came to mind as both of you were talking about this is that technology is also creative, at least for me, because it is not about something that already exists in the world. So it involves a kind of imagination. It’s not about new-for-newness-sake, but rather requires a contemplative sort of discovery or imagination to bring something to the world.

I can’t speak for other people, but for me, if technology and innovation have creative aspects that are situated, under what context are such technologies or innovation deployed and why?

- RS

-

I think you’re raising an interesting contrast—between creation and innovation, right? TN, how would you differentiate between the two?

- TN

-

Well, I would go back to recovering the root of those terms. The root of the word technology comes from techne and logos. I don’t mean to sidetrack by going to the root of these terms, but it’s actually a function of not understanding the root or the meaning of these terms and using them casually in such a way that they’re appropriated with different cultural associations. Maybe it’s just part of my training that I have to go back to the definitions and meaning, however transitive they might be. So from the Greek term techne which is craft—the application of a particular technology. In the dictionary, it’s the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes. From Greek, tekhnologia which means “systematic treatment.” The suffix -logy is discourse. That’s technology. Innovation is about renewal, from the Latin root, innovat, which means renewed or altered, with in- as “into” and novare as “make new.”[1]

So I think these two words are closely aligned because they both are about systematic understanding. And obviously, as we know, systems and structures are epistemologically rooted. But the idea of knowledge that is applied, for me, has so much creative potential and how renewal works, in context, is that you have to evaluate in order to know how to apply anew appropriately. So, my interest in operating in these worlds is that there’s a kind of constant analysis and reevaluation. - MC

-

I appreciate the impulse to recover these terms through etymology, and I don’t mean to imply that funding is available simply by claiming “innovation”. But honestly I think it’s a little disingenuous to replace “innovation”—as the term is most commonly circulated in academia and industry—with “renewal.” I guess, for me, the connotations and associations around words like “innovation” are just much more salient than their etymology. So, again, my problem with “innovation” is that the term’s common use seems to be preceded with the idea that the new is necessarily going to make things better. I see that mentality as closely adjacent to a kind of economic expansionist notion that is frankly at odds with ecological and social sustainability.

- RS

-

This discussion of “renewal” as a term is interesting, because unlike “innovation,” it suggests that there’s a pre-existing context. Perhaps “renewal” can stand in contrast to this idea that there is an unspoken—but assumed— beneficiary of all of this “innovation,” which I think disturbs me as well: that there is a concentration of expertise coming from certain centers of production, along with the assumption that the knowledge that results will inherently be good for whoever receives it, right? It raises these questions of who is not in the conversation, what need is being manufactured for the purpose of creating a market, what already-existing intelligence is being ignored, or who's going to have to deal with the aftermath of what’s being produced.

- TN

-

You're including the human factor in it. Like who is it for and who creates it? Who is the beneficiary? Who is the one producing the technology? And, beyond the elated euphoria when something works as intended, there’s the question of ethics and social implications that need to be weighed with the human factor.

- RS

-

There’s been this really interesting thread of computational work recently that deals specifically with expertise, the idea that it might not be possible to open up the production process completely because of questions of technical knowledge, so how do you interface or collaborate or address the knowledge gap?

I think about this a lot, as someone who studies both computational processes, and also how they exist as designed objects once they’re out in the world and have become normalized. I see this with the rollout of technologies of police surveillance: these are critical issues, happening in real-time, but because of the gap in technical expertise, or even the way certain academic discourses are formulated, a lot of the people who are most directly impacted by them are not taking part in the conversation. This goes beyond just increasing representation within centers of “innovation”—although that’s incredibly important. It’s also about rethinking the boundaries between these centers of knowledge production—for example, the academy—and other communities; how to break it down in ways that are actually meaningful and have a material impact towards questions of social justice.

It’s been interesting to see examples, over the past year at Taubman and in these Gradient feeds, where different people are working on related questions: ones that might rethink not just the premise of “innovation,” but also ask what different models might look like. Precisely because of questions surrounding expertise and how impenetrable it can often be; these approaches seem to prompt collaboration and/or interdisciplinarity.

As a design discipline, architecture also has this social component, which can be a compelling opportunity to try to bridge the knowledge-gap and make it less one-directional, or to rethink the relationship between the designer and the intended end-user, perhaps towards a more collaborative or co-productive model.

-

Mollie Claypool, who contributed to an earlier Gradient feed, has talked about working across expertise through the design of tools in her robotics projects: that the tool can be a way to bridge these gaps, and to move beyond a gendered (and ableist) relationship to physical strength, but also that this approach has required partnerships with people who have community-based design expertise. Similar questions came up during the doctoral colloquium this year, because of the people who were involved [PhD candidates and invited guests] and the kinds of work they are doing. Yi Chin Lee, who is working with Sean Alquist, raised some of these questions around the work they are both doing with neurodiverse communities [Figs. 6–7]. We had a really good conversation with invited guest Felecia Davis back in May: the topic of positionality came up, as undertaken in the social sciences—which typically involves reflexivity about your own identity and how it influences the forms of knowledge you produce, as well as the ground rules for collaboration or community engagement. Felecia brought this into the realm of computation by describing how craft can be a low-expertise medium to navigate some of these questions, particularly around technical knowledge and computation.

[Figs. 6 & 7] Workshop at the ORCHID installation in Omaha, Nebraska, for the Common Senses Festival organized with Autism Action Partnership. Children with autism and their families participate in the making progress to shape the multi-sensory nature of different facets of the ORCHID environment.

- TN

-

I think the reference to crafting is that bridge. At least in my background in terms of clothing production, sewing and textile work, there’s knowledge that’s much more embedded in ourselves than we give credit for sometimes. I think today, there is a wider recognition of one’s knowledge as expertise. But I want to qualify that knowledge is a set of systematic skills or ways of thinking. Being an expert means that one possesses a set of skills or know-how that could be directed toward something. Any maker in architecture will have some level of crafting. A former student had previously mentioned that digital fabrication took away his bad handcrafting because it’s mediated through other tools. In the case of computational design and digital fabrication, it is a learned set of skills and knowledge, a form of training. Training, whether highly technical or even intellectual, is a set of skills that are learned, even improved upon. Here, I’m not necessarily valuing one mode of learning over another, for instance informal vs. formal. But I think expertise is built over time. I don’t want to, in the same sentence, level expertise for everyone as if someone’s forty-year career is the same as another person with two years under their belt. I think the examples you gave are about making a set of knowledge accessible to a wider audience, that’s the work—that the beneficiary of that knowledge is not bound within an elite class, but rather could engage a broader segment of society that ranges in different levels of expertise.

I see software development as intrinsic to bridge knowledge gaps in that way. For instance, the technical knowledge to write codes for tool operation or a software like Photoshop takes a tremendous amount of technical knowledge. However, some of these software are by design, enabling someone with little technical knowledge to accomplish something. I remember learning specific codes for building websites in the late 90s, and then all of a sudden, there’s a proliferation of software that are platforms for building websites, without needing to learn which number is which color, etc. But there is still work in developing the software for a specific application. That is a form of technology. The software enables someone with little technical skills to do something. Look at Midjourney. I think ultimately, it’s about who that technology is made for and why. The internet is also a good example. It was commissioned by the Department of Defense to access remote computers, and clearly, it’s now used for many other things and along with it, a host of unintended and intended problems and benefits. The values are constantly being assessed and evaluated.

- RS

-

This also touches on different learning styles and different ways to acquire expertise, something that Kathy Velikov and Shelby Doyle discussed in their piece back in the fall, and that Yana Boeva and Vernelle Noel have also written about recently in their work on craft and feminist computation: this idea that computational knowledges and education have been socialized as very linear, rational, masculinist and white, and that all of these attributes have been accepted as defaults. Like you need seven semesters of computer science to be able to do anything computational, right? Whereas, if you come at it from the craft perspective, which is actually much more akin to the way that most of us in architecture have learned anything about computation, perhaps it's more the model of, you find some tutorials and you try to figure it out, and you make a lot of mistakes and you ask your friends or your colleagues. Not at all to disagree with the points you are making, Tsz Yan, about respecting the time that goes into the development of skill and acquired knowledge, but perhaps just to emphasize what the route towards that acquisition can look like, or to reinforce the kind of variability that you're describing. Maybe this is another aspect of architectural culture with potential for alternate ways to engage with technology; ones that are less focused on “innovation.” It reminds me of what Jose Sanchez wrote about in one of the earlier feeds: the right to repair, or to work in a less professionalized way with technology, as a different mode of engagement.

- TN

-

I agree. There’s a number of contributors to this year’s feed that explicitly describe their work and motivation as stemming from the desire to reassess inherited values, or even restructure the dynamics of prescribed forms of power structures that have previously proven to serve one segment of society at the expense of others. I think what I appreciate from all the contributors are the careful and nuanced inquiries to not just unraveling the issues, but providing productive approaches to reorient values, expectations, and even who the participants and audiences are. I don’t know if that begins to address this question of solutionist rhetoric. In some of the examples you mentioned Rebecca, they are more about alternative approaches. I’m not sure newness is the primary mode of evaluation but rather how alternative approaches could potentially address serious problems in our society whether it’s social or environmental.

- MC

-

I think the turn towards “craft” in this conversation, as a way of thinking about different, perhaps non-solutionist approaches to technology and expertise is really interesting. Tsz Yan, in a way I guess it gets back to your example of the pen that is used for stabbing instead of writing. And I do think it has to do with the way many designers and architecture students use software and other technologies. We cobble together functionality across multiple softwares and platforms, often misusing tools like physics engines or animation software for purposes unintended by their creators.

In a sense, this way of engaging understands ubiquitous technology as a context for production that can be critically appropriated. I think Andrew Kudless touches on these ideas in his piece on Midjourney.

But I do think there is a difference between that kind of engagement of technology as context, and a foundation-level approach that truly addresses the questions of inclusion that have been discussed here. To extend the earlier example of website creation, does it become more inclusive through the tool that allows you to select a color instead of entering a code? Or does the moment of exclusion occur when the possible colors are chosen?

Making knowledge accessible is different than rebuilding knowledge in the interest of more inclusive epistemologies. Enabling the layperson’s use of technology through UX design is different from the robust co-production between technologists or layperson to reframe instrumental goals. The latter is a much thornier problem.

-

I don’t see an easy answer to that problem and the very high threshold of knowledge necessary to enter a conversation. But the ideas about recursive relationships between technologists and end-users, or even community groups, that Rebecca mentioned are compelling. Tsz Yan, where do you see this playing out in the contributions in the feed, or among our ACDCC colleagues at the college? I think of the turn towards community engagement within our MSDMT degree, for example.

- TN

-

Across all the contributions, and more broadly for the computational design and digital fabrication community is the shift away from just making highly technically-crafted objects. I think this area of work is mature in the way that we’re self-critical, and are directing our efforts toward outcomes that have broader impact. For instance, none of the articles are strictly about formal aesthetics, they are socially charged and conscientious of inclusivity, asking who really are the beneficiaries, or who are we working with, and for. Mirroring the broader emphasis in architectural discourse in the last two years of an overhaul: by taking responsibility for our actions related to design and the built environment, and understanding the ramification for not just the outcome but the process of how we get there.

[Fig. 8] SPLAM pavilion/outdoor classroom at Epic Academy, Chicago, 2021. Kendall McCaugherty © Hall+Merrick Photographers.

-

In that respect, I think we’re definitely more self-critical. We see this, for example, with the MSDMT pedagogy: the work Rebecca mentioned earlier, that is being done by Sean Ahlquist and his students. In the MSDMT capstone last year, and again this year, Sean is partnering with the Center for Independent Living in Ann Arbor (AACIL). This group is run by people with disabilities, helping others with varying levels of disabilities to live fully and independently. The capstone course collaborates with members of the AACIL to develop concepts and prototypes for environments that are responsive to ever-changing needs and interests. I think the motivation of such pedagogy is to engage with the local community to move beyond the association that digital fabrication is only about the testament to technical mastery of some material process. And after it’s done, it’s just cast into the world and we’re stuck with it.

Even the SPLAM project that I worked on with Wes McGee and SOM last year was not just about material efficiency and optimization of timber construction—though we do need to develop more sustainable building practices. That project was partnered with Epic Academy, a Southshore public high school in Chicago where the built pavilion is ultimately a flexible outdoor classroom for the school [Fig. 8]. It’s not a demonstrator pavilion for the sake of just being a proof of concept. The afterlife was important. Who we worked with was important. I think that is where there’s incredible agency in what we do, not only to respond to climate change imperatives but interrogate who we work with and for.