In the midst of the Western emerald cities of Oz we have crime, greed, and homelessness. The architects of the twenty-first century, almost assuredly, will have to build a way out of a triple crisis of the materialist, capitalist, and idealist modes of intellectual production. Something has to give.

This unblinking assessment of contemporary architectural practice does not come from a recent zoom roundtable, an activist’s twitter account, or an incisive op-ed. It was written by Robert Farris Thompson in 1995, in the foreword to a publication on African nomadic architecture more specifically, on “nomadic women’s architecture,” a book he described as arriving “right on time.”[1] In the same foreword Thompson predicts that this work will gain traction as “surely one of the classics of twentieth-century architectural history.”[2] Today, his diagnosis of the challenges facing the profession still rings painfully true, but his prediction of a broad and enduring readership for this text on African architecture has not come to fruition. Somehow, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender [fig. 2], and more significantly, the oeuvre of its author Labelle Prussin [fig. 1], have slipped through the cracks of architecture school curricula.[3] Nevertheless, as the world’s population continues to suffer through a devastating pandemic, a book that details the cultural consequences of “sedentarization,” that suggests alternative scripts for collective creative action, that maps out the intersection of labor politics and gender identity, while describing architecture as a logistical process rather than a monumental product, once again feels “right on time.”

If one accepts the guiding premise of Other Assemblies, namely, that contemporary architecture is in the midst of a resurgent interest in tectonics, in the symbolic, social and affective capacities of material assemblies not merely to reflect cultures, but to participate in their transformation, then the African ‘tent-tonics’ elucidated by Prussin are well worth revisiting. Methodologically, her book models another mode of assembly, bringing together facts, images, vocabularies and stories to construct an architectural history around the concept of gender and the alterity of women’s worlds. According to Prussin, it is “the architecture of nomadism” itself which mandates this “innovative approach” and her critics frequently point out the underlying sympathy that seems to connect the author’s scholarly methods to the cultures she studied.[4] “Weaving” is the metaphor most often invoked to describe this bond, a word that alludes to a set of practices presumably absorbed over the course of Prussin’s fieldwork, then redeployed as an approach to history writing.[5] But this “weaving” is more than a structural metaphor (in the tradition of Semper). It describes an approach to assembling knowledge that takes special account of the social identities and the relationships connecting all those involved.[6] Prussin’s “weaving” is sensitive to rituals and routines, to the geographical distribution of resources, to power dynamics among actors, to the sacrifices they make, the time they invest and the manner in which all of these factors bear a reciprocal relation to built form.

[Fig. 1] Labelle Prussin depicted alongside Rudolf Wittkower in the Newsletter of the Society of Architectural Historians announcing her as the recipient of the SAH Founders’ Award “for the best article by a younger scholar in the Journal during 1974.” See Newsletter of the Society of Architectural Historians XX, no. 4 (August 1976): 4.

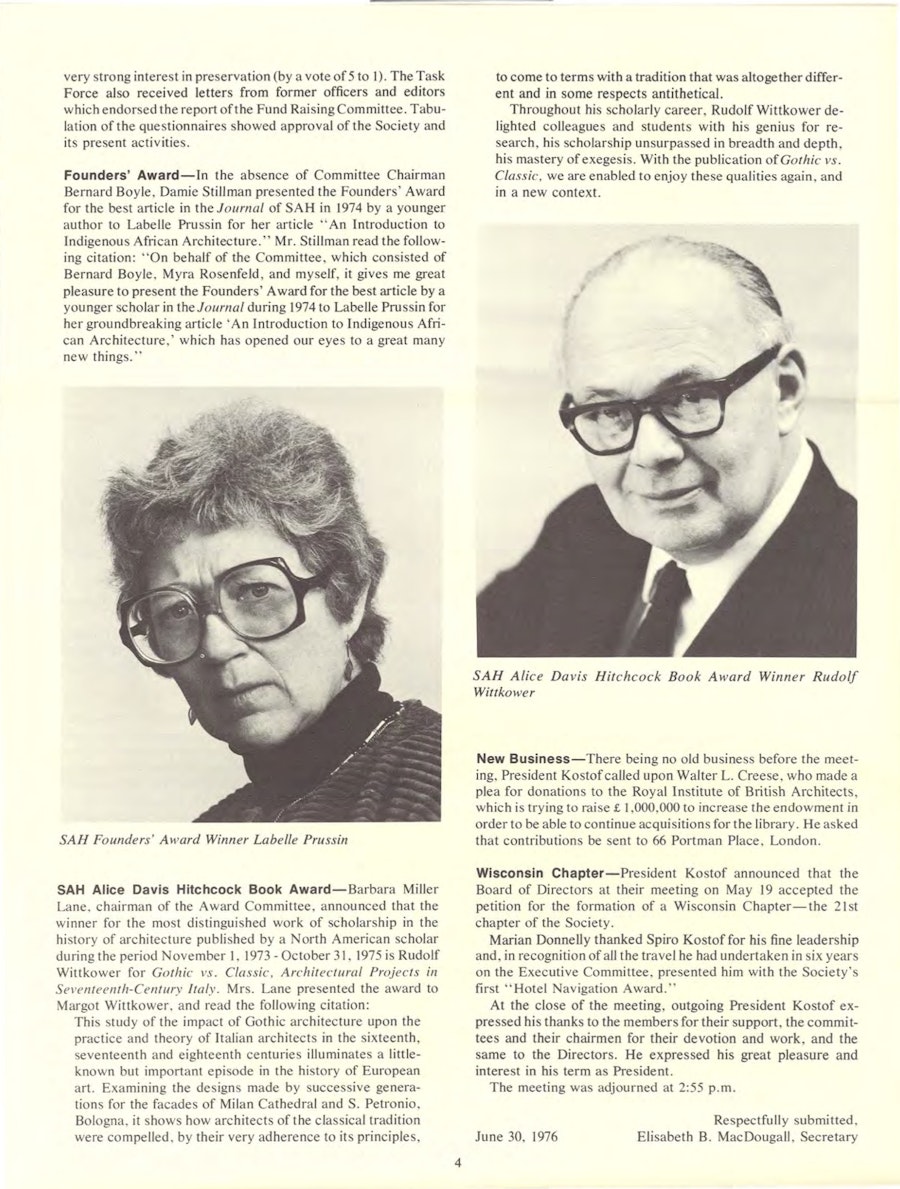

[Fig. 2] Labelle Prussin, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press and The National Museum of African Art, 1995)

As much as Labelle Prussin’s research on women’s nomadic architecture might resonate with present concerns, her book also merits reading as an artifact of activist scholarship developed within the context of the feminist movement. Prussin herself positions her research in relation to other examples of feminist architectural history.[7] In 1973, while teaching in the Department of Architecture at the University of Michigan and finishing work on her groundbreaking essay “An Introduction to African Indigenous Architecture”, Prussin encountered the work of fellow architect Doris Cole.[8] Prussin recalls:

At the height of the growing feminist movement, Doris Cole’s small paperback book (1973) appeared.[9] My intrigue with it had less to do with feminist consciousness than with a decade of architectural experience in Africa during which my scholarly appetite for the vernacular had been whetted. Plains Indian women had been building tipis for millennia in the Americas, just as their gender counterparts had been building yurts in Asia and black tents in the Near East and North Africa. It took little thought to make the analogy with the African nomadic women. Here, then, was a new kind of role model![10]

Cole’s book, From Tipi to Skyscraper attempted “to compile the first history of women in American architecture.”[11] Though Cole stopped short of connecting the project directly to the “contemporary women’s movement” she minced no words when it came to the facts: her study was written at a time when “approximately 2 percent of the architects practicing” were women and scarcely a single “conventional” source could be consulted to learn about the historical contributions of women architects.[12] Facing this reality, Cole sought to identify moments and spaces where “women were the architects of their communities.”[13]

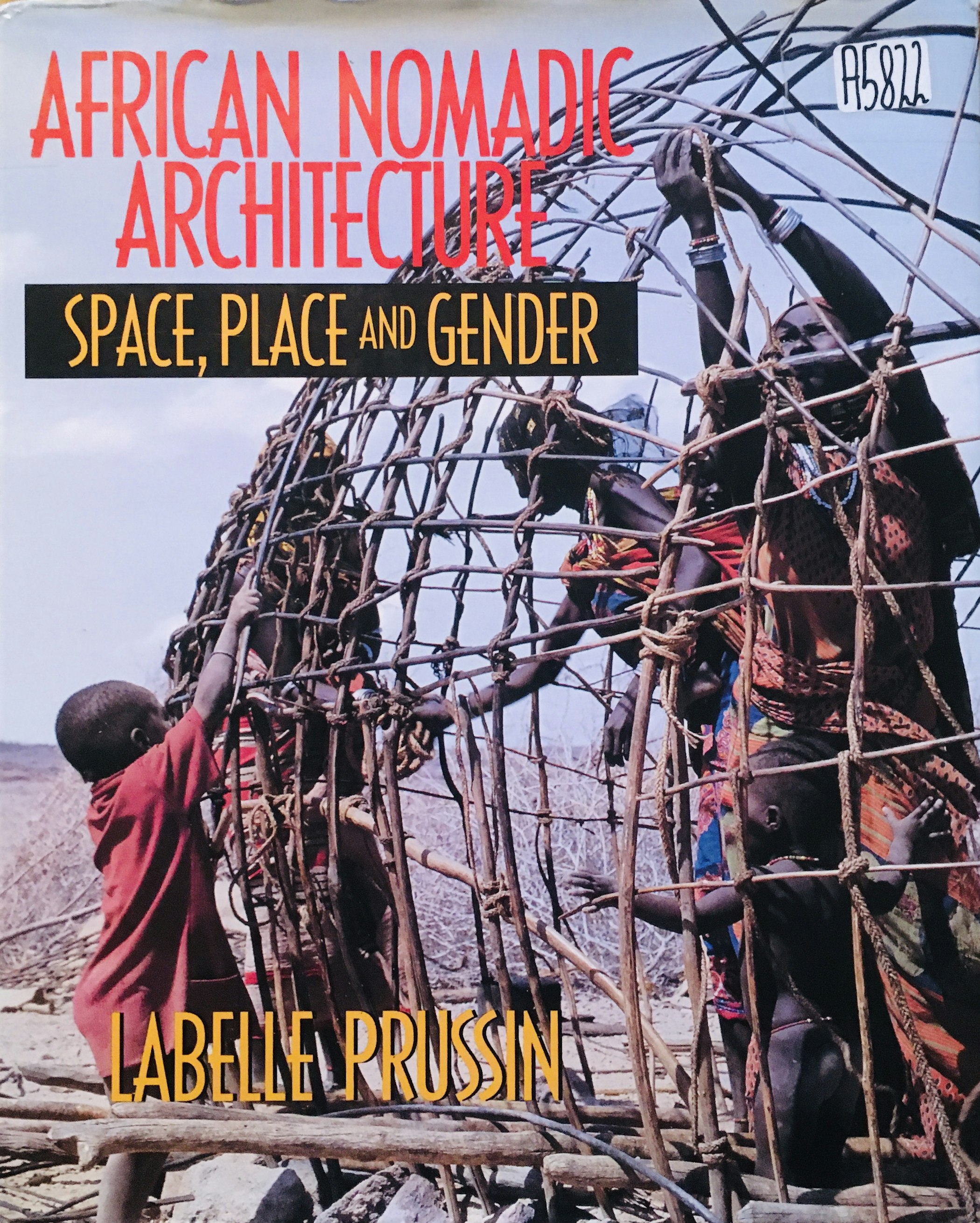

Prussin took up this search for role models, but her own experiences in Africa, practicing architecture and conducting fieldwork, shaped a distinct critical perspective.[14] Earlier in her career she had learned about the work of architects like Louise Blanchard Bethune and Julia Morgan while also realizing that these women had followed professional paths unavailable to most: “few of us were in a position to benefit from the kinds of social opportunities that led to sponsorship and patronage by the nation’s financial elites.”[15] Still, by naming these architects in the introduction to African Nomadic Architecture, Prussin signals that the book is as much a study of women architects as it is an investigation of African nomadic building. More pointedly, Prussin uses her fieldwork in Africa to break the historiographical focus on individual auteurs. In her introduction she points out the necessity—and ultimately, the inadequacy—of collections like Architecture: A Place for Women (1989) [fig. 3] and other projects that continue the male-invented art historical tradition of compiling and celebrating individual artists’ lives.[16] Instead, Prussin’s book aims to present an analysis of communities in which women architects collectively shape the built environment. Among the Tuareg, the Tubu, the Mahria and the Rendille, Prussin and her co-authors attempted to document “the complexity of the cooperative networks through which art happens.”[17] At the time of the book’s publication, some colleagues, both architects and specialists in African art, struggled with this concept. For many designers, the kinds of practices described seemed insurmountably distant from their own milieux: contexts that perpetually reinforce personal achievement through awards, magazine spreads and individual licensure. From the perspective of historians, the emphasis on “creativity in a collective context” risked a dangerous return to an earlier, insidious practice that essentialized African art as an “anonymous art, subsumed by cultural (often erroneously attributed) identity.”[18] Prussin acknowledges the real damage inflicted by this “intellectual error” while cautioning against an over-correction—an interpretive approach that ignores collective authorship “in order to validate African art in a Western construct, for a Western audience and art market.”[19] Ultimately, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender tries to avoid both traps, while dismantling the false binary of starchitecture vs. “architecture without architects.” Its message is clear: collective creativity is not categorically anonymous.

[Fig. 3] Ellen Perry Berkeley, ed. and Matilda McQuaid, assoc. ed., Architecture: A Place for Women (Washington, D.C. and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989).

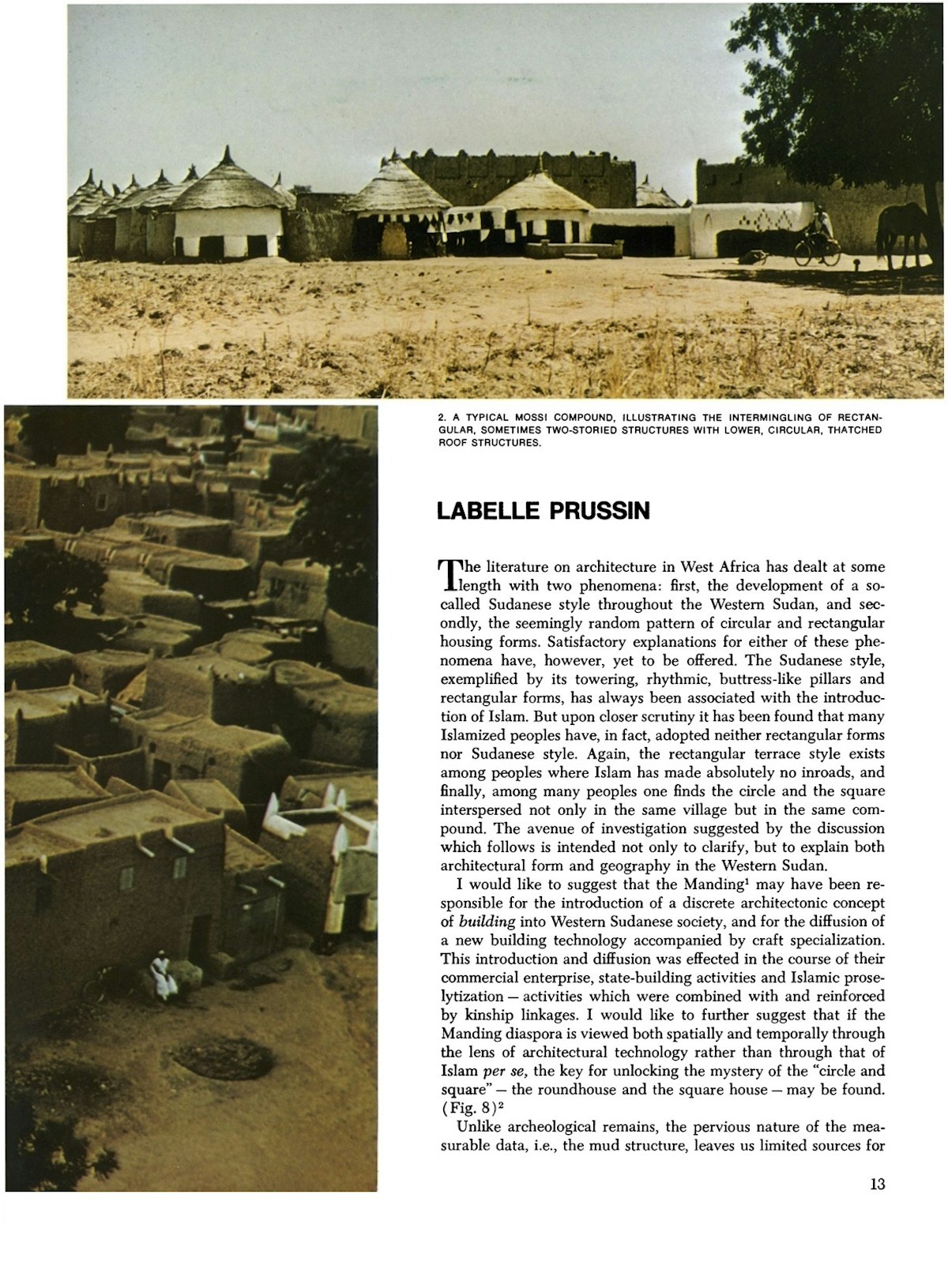

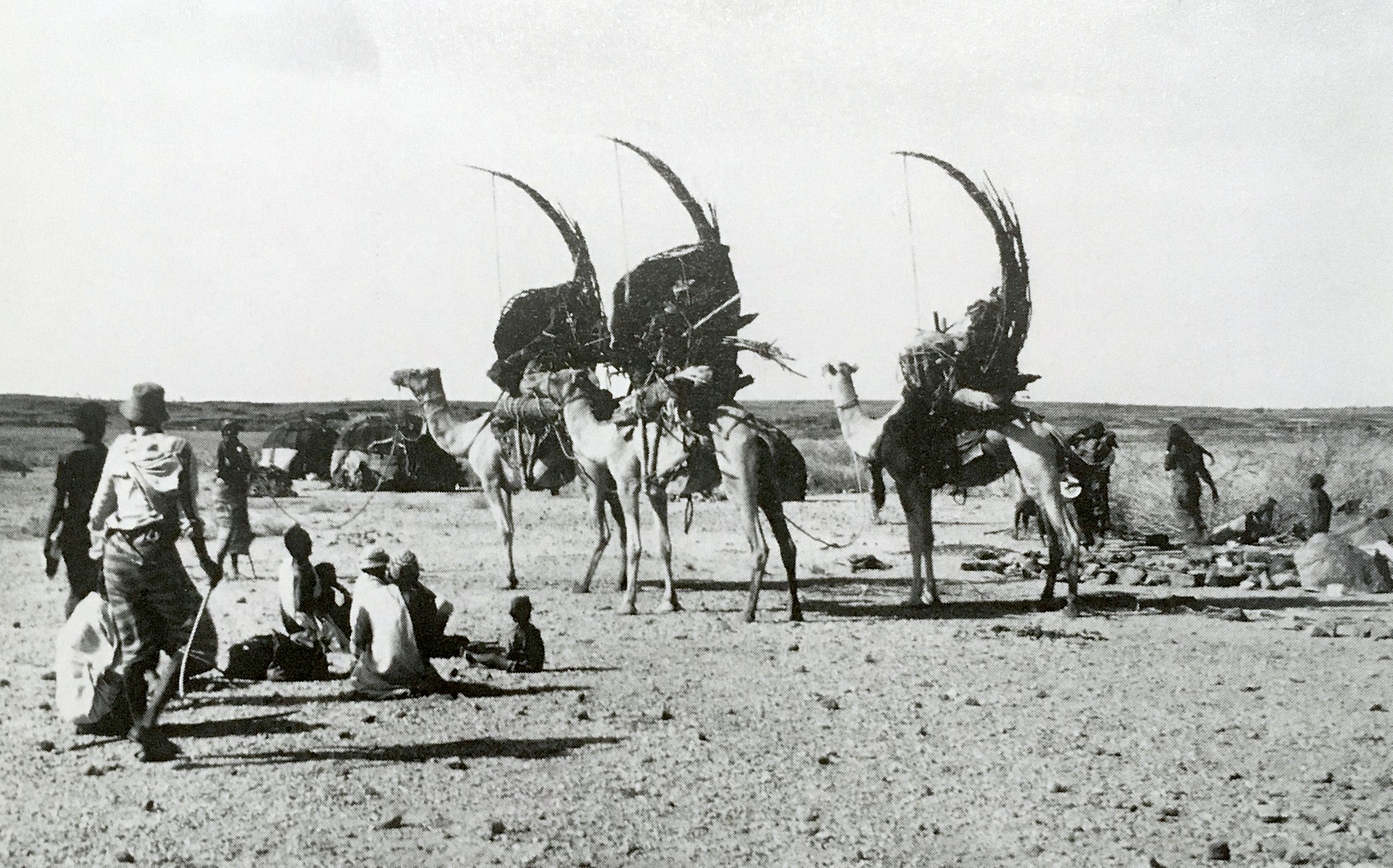

To that end, the cover of Prussin’s book features three Gabra women constructing a marriage tent [fig. 2].[20] This representation mattered to Prussin, given her own lived experience. She had hitchhiked across the country to enroll in the architecture program at UC Berkeley, one of the few departments to accept women applicants at this time. She earned her M.Arch from Berkeley in 1952 and later took a job at Kaiser Engineers, where she lobbied for an assignment on the Akosombo Dam project in Ghana.[21] Initially, the company rejected her requests, declaring the assignment unfit for “a white woman with two little kids."[22] But Prussin persisted and this self-advocacy set in motion the experiences that later shaped her scholarly contributions. In Ghana Prussin found work as an architect and planner on several government projects and spent time teaching at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi.[23] As her interest in African architecture grew, she published a series of articles—often accompanied by her own photographs [fig. 4].[24] Beginning with a text on “The Architecture of Islam in West Africa” in African Arts, she wrote on a range of topics including the architecture of the Manding, West African mud granaries, Fulani-Hausa buildings and traditional Asante architecture.[25] These essays were written over the course of a career that Prussin has called “a lifetime of wanderings across a multitude of physical and cultural environments.”[26] After leaving the University of Michigan she held teaching positions at a number of institutions in North America and Asia, while continuing to conduct fieldwork in Ghana, Niger, Nigeria and Kenya.[27]

[Fig. 4] Pages from Labelle Prussin, “Sudanese Architecture and the Manding,” African Arts 3, no. 4 (Summer 1970): cover (featuring a photograph by Labelle Prussin), 12-13, 16

[Fig. 5] The back of a Tekna Lansas tent in southwest Morocco, photograph by Peter Andrews, published in Labelle Prussin, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press and The National Museum of African Art, 1995), Fig. 4.1, 67.

[Fig. 6] Two Rendille women bending gaer sticks to create architectural components in northern Kenya, photograph by Anders Grum, published in Labelle Prussin, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press and The National Museum of African Art, 1995), Fig. 8.5, 157.

[Fig. 7] The rear reinforcing armature of a Gabra tent in northern Kenya, photograph by Labelle Prussin, published in Labelle Prussin, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press and The National Museum of African Art, 1995), Fig. 3.8b, 54.

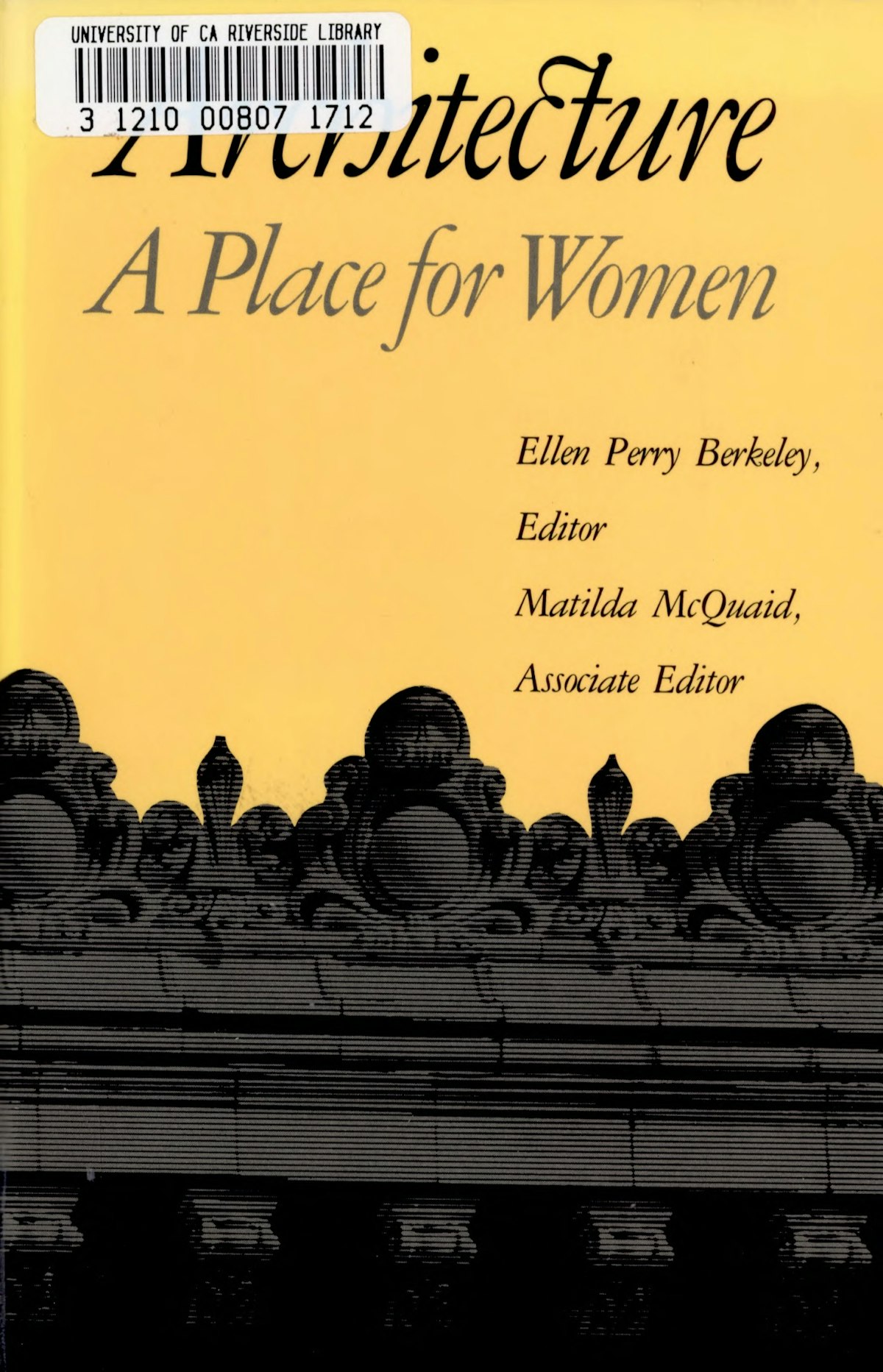

[Fig. 8] A mat-covered armature Kel Ferwan tent, Niger, published in Labelle Prussin, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press and The National Museum of African Art, 1995), Fig. 5.2b, 91; reproduced from René Gardi, Sahara (Bern: Kümmerly & Frey, 1970), 100.

By the time African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender appeared, Prussin had been researching building practices in diverse African contexts for almost thirty years. The book was originally imagined as an exhibition proposal for the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C. It then morphed into a film script for a documentary on the Gabra marriage ceremony. This project, in turn, required additional fieldwork in Kenya, which eventually inspired the book’s final, multi-authored format. In many ways the documentary film, produced and directed by Peter Oud, provides a necessary counterpart to the academic text and its static illustrations [figs. 5-8].[28] Nagayati: Arts and Architecture among the Gabra Nomads of Kenya (1991) documents the wedding ceremony of Woto Mamo Wako and Joseph Jatani Diba, a Gabra bride and groom from separate villages. As Prussin’s script explains “house and marriage ceremony are synonymous in the Gabra language.” Over the course of the film, one sees a Gabra structure disassembled, packed, transported, unpacked and reassembled, no fewer than eight times [figs. 10-11].[29] Unbuilding and building form the basis of the rituals that bind the couple together. As the film opens, Joseph’s mother is busy making preparations for the journey to the bride’s village. She completes a complex tectonic metamorphosis, reconfiguring the disassembled wooden ribs, woven mats, plaited ropes and cowhides that constitute the family’s home into a new structure: a palanquin, a more compact, protected litter that will sit atop one of the family’s camels and provide her shelter for the trip to the bride’s village [fig. 9]. Once Joseph’s family has completed their journey, this transformative dis-aggregation is mimicked in the pivotal ritual of the marriage ceremony itself, but with an essential difference. This time, it is the bride’s mother’s house which is taken apart. While normally, she would direct this process herself, in the marriage ceremony she must stand silently by as a group of women, comprised of friends and family, take apart the structure and divide its contents into two piles. These women choose which elements will be combined with freshly completed ropes, ribs and mats to form the bride’s new home. When the sorting is complete, Woto’s mother takes stock of the remaining elements before quickly reassembling the residual materials into a smaller home for herself. Watching these architectural transformations unfold in real time, one comes to understand how generations of Gabra women have precisely calibrated their tectonic systems to conserve resources while simultaneously preserving cultural formations.[30]

Whether the nomadic Gabra women depicted in the film would identify themselves as “architects” (or rather the equivalent in their own language) remains a valid question – one Prussin herself poses in the introduction to her book.[31] In a review of African Nomadic Architecture, Victoria Rovine points out the difficulties one creates by applying received definitions of “artist” and “architect” to the sub-Saharan context.[32] Is it accurate, or even fair, to use the words “artist,” “designer,” or “planner” when the creative production of these women is neither structured as a profession, nor a hobby, but is deeply embedded in everyday life? For some avant-garde artists this synthesis constitutes the highest ideal of art. But what if that fusion of art-and-life is not the result of a conscious choice, but part of a system developed as a means of survival? Prussin expresses her interest in studying, celebrating, and upholding “women’s work” and writing explicitly against those texts “which focus on a cultural construct that denigrates those tasks.”[33] While at the same time she is careful not to “romanticize or glorify domestic labor.”[34] Ultimately, both Rovine and Prussin conclude that there is good reason to apply the terms “architect” and “artist,” however alien they may be to these contexts. Asserting that within these societies, “all women are artists,” puts a healthy pressure on existing definitions of the word.[35] For Prussin, the pathways of African nomadic cultures present an opportunity to confront presuppositions and re-examine constructed models of reality such as “Western and non-Western,” “feminine and masculine,” “works of architecture and buildings.”[36]

[Fig. 9] Gabra women securing tent elements that have been reconfigured to form the camel litter armature, northern Kenya, photograph by Labelle Prussin, published in Labelle Prussin, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press and The National Museum of African Art, 1995), Fig. 10.7, 199.

[Fig. 10] Stills from Nagayati: Arts and Architecture among the Gabra Nomads of Kenya, directed by Peter Oud, script by Labelle Prussin (1991; Smithsonian Institution).

[Fig. 11] Stills from Nagayati: Arts and Architecture among the Gabra Nomads of Kenya, directed by Peter Oud, script by Labelle Prussin (1991; Smithsonian Institution).

A book on African architectural history that opens with a brief survey of the existing feminist historiography of architecture, that openly acknowledges the crucial role of the author’s subject position as “architect,” “wife and mother” and includes a discussion of “code-switching” might have caught some readers off guard, but most critics appreciated the clear identification of Prussin’s motivations and perspective.[37] Prussin was not only interested in encouraging more women, and specifically women of color, to become architects, she wanted to suggest that designers might rewrite the script of professional practice. She offers not so much a guidebook for those looking to find success within the bounds of the existing profession, as an architectural history doubling as a template for alternative modes of reality: “It is hoped that the results of this effort will fire the imagination of a new generation in ways the nomadic experience did for me and my contributors.”[38]

According to author and psychologist Lisa Aronson, “gender” is the true subject of Prussin’s book.[39] It is impossible to describe African nomadic architecture without acknowledging what Prussin calls “the dichotomy of gendered worlds (in the sense of exclusion, not contradiction).”[40] These gendered worlds structure public and private spaces in different ways among the Tuareg, the Tubu, the Mahria, the Rendille, the Tekna, the Trarza, and the Brakna. The exclusivity of many spaces within these communities reinforces the “invisibility of women’s labor” and “the invisibility of women’s creativity in the nomadic context.”[41] Indeed, one reason so many of the art forms, techniques, and rituals practiced by these groups have been overlooked by generations of previous writers, anthropologists and historians, is that the researchers (as men) were not admitted to the interior spaces where the labor and creative expression took place.[42] Prussin, along with Uta Holder, Amina Adan, Arlene Fullerton and Odette Du Puigaudeau were able to access and document these spaces in part because of their gender identities.[43] What they encountered was a complex system of:

… woven tapestries, textiles and looms, leather pillows, carrying and storage sacks, wooden bedframes and their supports, assembled by means of metal and leather ties, enveloped in leather and fabric coverings, woven and embroidered room dividers and sleeping backdrops that hang like altar screens, plaited mats and ropes, tent armatures, carved wooden poles, and storage racks…[44]

These are the components of African nomadic architecture, most of them crafted, assembled, disassembled, prepared for transport, unpacked and re-assembled by women.

Aronson notes how Prussin and her collaborators were able to use “architecture as a window on the ways in which African nomads construct gender.”[45] The gender-discrete division of labor creates the conditions whereby women complete the work involved in design, planning, fabricating and building, preserving and educating the next generation of architects. Knowledge about tent construction, disassembly and transportation is shared between mothers and daughters from an early age. Among the Rendille in northern Kenya, for example, young girls learn how to create miniature tent armatures from twigs and cover them with leaves, later reconfiguring these materials into tiny camel loads.[46] This separation of tasks by gender is one practice that has contributed to the extreme continuity of African nomadic building traditions over time. As noted by architectural historian Nnamdi Elleh, Prussin assembles a variety of evidence showing the use of tent structures by African cultures dating back to extreme antiquity. Among the most compelling sources are a group of Tassili rock paintings that predate ancient Egyptian architecture by multiple millennia [fig. 12] and “give credence to the suggestion that some of the current tent building practices of Fulbe, Gabra, Mahria, Rendille, Somali, and Tubu have been going on for thousands of years, and may have been passed down by women from generation to generation.”[47] The other side of this extreme durability, or preservation, of building techniques and forms, is the fixity in relationships among gender and age groups, accompanied by hierarchies and inequities, with architecture playing a key role in perpetuating imbalances.

[Fig. 12] Rock painting at Sefar, Tassili n’ Ajjer, Algeria, from ca. 6,000 BCE, photograph by George Holton, compare to Fig. 1.3c in Labelle Prussin, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press and The National Museum of African Art, 1995), 4.

It is important to note that these divisions are not always expressed, directly, in terms of gender within the languages of African nomadic communities. Prussin gives the example of the Gabra who differentiate forms of labor by bodily position: “standing is work, sitting is resting.”[48] By implication, any tasks completed while sitting do not qualify as “work.” Since herders stand, they are working. Whereas the transformation of raw materials into architectural components, or proto-components, usually carried out in a seated position, does not constitute “work.” This distinction—standing vs. sitting—divides labor among the Gabra, but the herding jobs are most often conducted by men and the architectural tasks are largely carried out by women. Prussin can identify these women’s efforts as a form of architectural practice, but within the Gabra culture the connotation is clear: because much of their labor is conducted while sitting, “women do not work.”[49] The fact that Prussin identifies these distinctions, carefully, again points to the fact that, despite her search for “role models,” her text is not a romanticized glorification of a culture in which women architects hold power.

Prussin’s discussion of the Gabra understanding of “work” is one moment among several in the book where she quotes an indigenous voice (in translation), and this begs the question: if the goal is to better understand African nomadic architecture, would it not make more sense to learn directly from an indigenous source? The simple answer is, yes. Prussin herself acknowledges as much in the foreword to her earlier book, Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa (1986): “We are aware that with the removal of each successive cultural veil, there will always be, like the nets of the Sorko fisherman, another hanging before our eyes.”[50] Nevertheless, by framing an assessment of Prussin’s work only in these terms, one diverts all attention from the kinds of knowledge that can be gleaned from her book, and perhaps can only be gleaned from her book. African Nomadic Architecture is far from unimpeachable, particularly when judged from within the bubble of contemporary norms and standards. It is not entirely free of essentializing language and interpretive dead ends. At times, the arguments flow blindly down the path of phenomenology without full awareness of the consequences. But at the end of the day, Labelle Prussin’s work accomplishes something important. It demonstrates one way to collect and share information from distinctive culture contexts in such a manner that this knowledge puts pressure on the parts of one’s own familiar systems in desperate need of change.