Interview recorded on June 7th, 2020, with some contributing questions from The University of Michigan Chapter of The Architecture Lobby.

- Daniel Jacobs (DJ)

-

Hi Peggy! How are you, where are you, and what are you thinking about right now?

- Peggy Deamer (PD)

-

I’m in Kaiwaka, in New Zealand. Kaiwaka is about an hour and a half north of Auckland, in the North Island. It’s rural, very pastoral, very beautiful. With COVID, I have been lucky to be in a relatively healthy place, with a government that is dealing with the crisis well. But I have to say, what I'm feeling right now is my distance from Black Lives Matter protests. It doesn’t feel good to be far away. Right now I am thinking, how do I get home?

- DJ

-

Given this current context, who does the Architecture Lobby serve?

- PD

-

The Lobby serves architectural workers. I don't know how else to say it. I think of architectural workers as not just employees, but employers as well. So, the Lobby argues for all architectural workers to be more relevant, to be paid fairly, to have a decent work-life balance, to have a place at the table of power. I believe that how you are rewarded monetarily is related to your relevance and your power. We might think that our profession is a calling, and that giving our gifts to the world is our contribution and source of power. I don't believe that. One might think that there is something to gained by sacrificing fees for social and or cultural relevance, but I suspect instead that 1), we are sacrificing fees for things that bring no social or cultural kudos, i.e., not charging what we should for our private clients; and 2) that whatever cultural or social kudos we do gain when sacrificing fees have little or no traction in the long run; we get written off as willing chumps.

- DJ

-

What do you think architectural activism should look like right now?

- PD

-

This isn't necessarily related to activism, although maybe it's a precursor to activism. One thing I have become aware of, particularly with distanced learning and COVID-19, is how important it is to recognize that we have multiple subjectivities: that we are not just students, or alumni, or members of institutions, or just architects. There are many different facets to who we are that are suppressed by many institutional associations. Institutions like the AIA, or your office, or your architecture school make sure that your primary identity is to that club. Beyond that, architecture culture might tell you to bow to the club of formalism, or plurality, or avant-gardeness. It’s okay to be devoted to a club, but it doesn't help to be a citizen in the world when you have been told to commit to a singular identity. I think there is a relationship between activism and recognizing who you are in multiple ways. I suspect that most architects, when they started architecture school, wanted to do good for society. Instead, they were pulled towards their school's formal paradigms.

[Fig. 1] We Are Precarious Workers protest

- DJ

-

Why do you think that is? Why would an academy see it as advantageous to encourage that singular identity?

- PD

-

To protect its own endowment. We can talk about all the ways that happens, but as an institution, it has to preserve its brand, and that brand ensures donations and security of the endowment. They don't want to offend anybody. As soon as you are political, you might be offending a donor.

- DJ

-

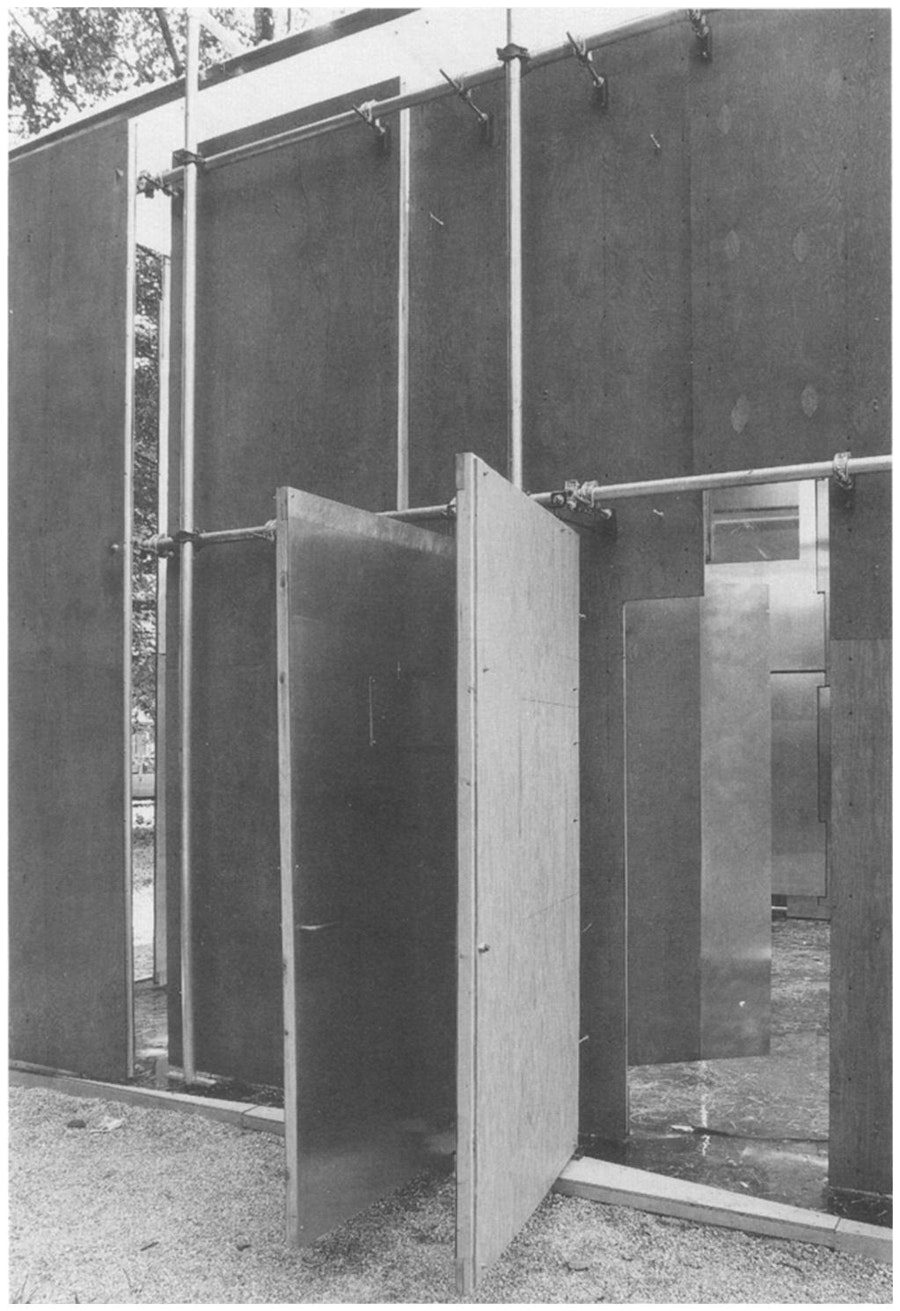

You are arguing that the academies and institutions like the AIA actively encourage architects to form a single monolithic identity, while instead they should advocate for a true multiplicity of subjects. Some of your earlier research and writing deals with this same issue: specifically, the relationship between aesthetics and psychoanalysis, gender, and sexuality, and how the surface, detail, and textures of a building can reflect or inform subjectivity[1]. In a recent paper you delivered at The Cooper Union, you invoke a similar reading of the relationship between architecture and subjectivity in John Whiteman’s Divisible by 2 pavilion in Vienna from 1988[2]. How has this thread of research informed your politics, and do you think the agency of the material of architecture holds up in today’s social and political climate?

- PD

-

I appreciate the question, because I am not often asked about that connection, and it matters to me. I started my academic life trying to understand how we, as architects, promote certain formal paradigms; I studied formalism. The relationship between the maker, the object, and the viewer/user became a focus. In this research, I have been interested in theories of form that foreground the maker and the position a maker takes vis-à-vis her object of intent. Adrian Stokes was interested in that position, and to understand it, he used the psychoanalytic theories of Melanie Klein (who was his analyst). Through Stokes, I became interested in the way that psychoanalysis was unpacking a deeper sense of what motivates our approach to—and creation of—the exterior world: the terms of our desires, our need to project ourselves onto our environment and make things. Psychoanalysis asks what part of that subject-object relationship is outside of our conscious control and why. This inquiry went from Klein to Lacan, to Deleuze and Guattari, to Žižek—all interested in our uncontrolled but powerful object relationships. I wanted to know about those relationships because I did not want to be naïve about the forces at work in my (or our) acts of aesthetic production.

The work on Stokes also connected me back to John Ruskin, who addressed similar questions from an ethical, not psychoanalytic, perspective. Ruskin drew the ethical connection between not just the maker, the object, and the viewer/user, but also the relationship, in architecture, between two makers: the designer/architect and the builder. So that got into the mix.

At a certain point, this work that I was doing on form and aesthetics—in architecture, on detail, and the relationship of craft to design—all of these questions appeared to be importantly embedded in the larger one of can you even put food on the table? I became aware that it is a luxury to think about the aesthetic thoughts of the maker, who is positioning-herself-in-relationship-to-an-object, when her real material conditions are one of struggle, impoverishment, and precarity. This realization clearly related to research I was doing, and courses I was teaching, on Critical Theory and the Frankfurt School.[3]

- DJ

-

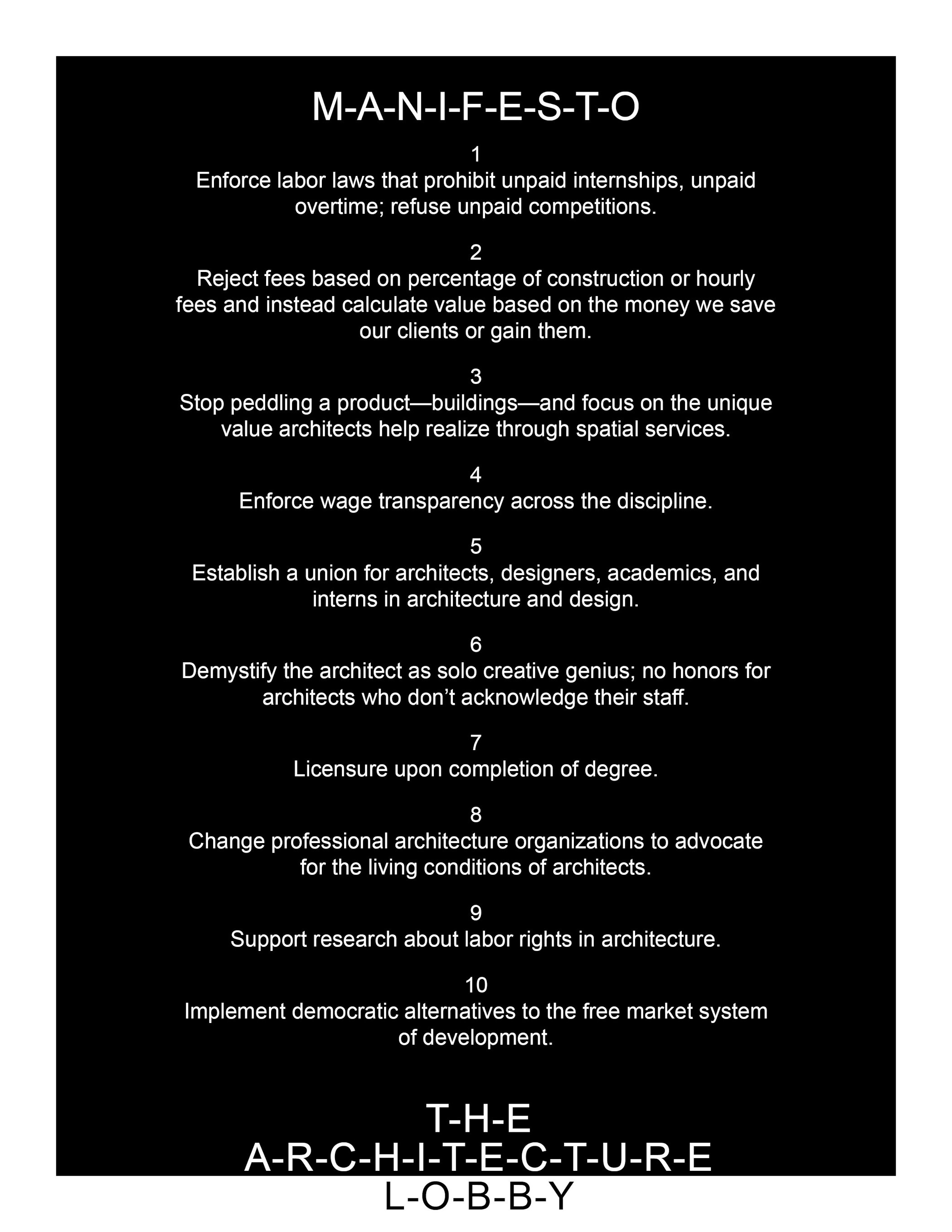

I want to shift the conversation from one about the politics of aesthetics to one of the aesthetics of politics, specifically political action and activism. The Architecture Lobby often invokes aesthetic sensibilities rooted in the working-class struggle in the early 20th century: from confrontational modes of protest, to bold sans-serif graphics, to using a manifesto to make demands. These are explicit tactics rooted in a type of labor organizing rarely associated with professions like architecture. I know the Lobby’s aesthetic sensibility is very important to you. Could you respond to the idea that these might be misplaced tactics for the profession of architecture?

[Fig. 2] Divisible by 2 by John Whiteman

[Fig. 3] Divisible by 2 by John Whiteman

- PD

-

My first thought is that labor struggle is not stylistically variable because the struggle itself doesn't change with time; this is a struggle that goes back to the 12th century. Doing something hip and groovy that addresses the newness of this condition seems wrong. If Lobby graphics speak to the struggles of the working class in the late 19th and early 20th century, so be it. I don't think we should be ashamed of recognizing ourselves as working class, and for people who are startled by that identification, I hope it sparks interrogation about class. If we are not working class, what are we?

[Fig. 4] Lobby Manifesto

- DJ

-

Architects definitely are startled by the idea of the architect as working class. Could you break down that argument?

- PD

-

Well, for me, the two main classes have been and still are those who own capital and those who work for those who own capital. Architects work for those who own capital. I guess there are two ways of thinking about that. One is just the reality that we are not of the same monetary class as most of our clients and developers, and we have more to gain by aligning ourselves with construction workers, who are closer to our reality. The other way to look at it relates to my argument for de-professionalization. That research has led me to see the difficult conditions within which professionals are identified. It keeps intact a false idea that the “learned professions” are not just ordinary businesses and those in them are not everyday workers, even though all of the antitrust laws insist that we are. We are not protected, in any way, from antitrust laws that say we can only serve society by competing, like all other businesses, against each other. I think being a profession is the worst of both worlds, which keeps intact a certain sense of elitism that we congratulate ourselves for, but stops us from actually competing well, because we are above learning “business.” If we didn't function as a profession, we might be more inclined to not just to be business savvy as employers but to unionize as employees. Unions are exempt from antitrust laws that otherwise make it illegal for a “profession” to discuss both wages and fees. So, let's get out of the mode that tells us what we can or cannot talk about and get into one where we can begin to talk about our real material conditions.

[Fig. 5] Unionization poster

- DJ

-

Both unionization and cooperativization are important threads in your current research, alongside active projects by membership in The Architecture Lobby.[4] I understand you have spoken with architecture cooperatives and unions around the world and are even discussing legal conditions around forming professional co-ops in the United States with a group of lawyers. What insights have you unearthed in the course of this research?

- PD

-

For me, this is part of the ongoing research about how American democracy foregrounds competition. As I suggested before, I am very interested in the relationship between antitrust laws and the profession of architecture. The one guiding principle of antitrust laws is that we have to compete. I don't think the founding fathers, in the Bill of Rights or in our Constitution, said that competition was the basis of our democracy. We also find this in the research on cooperatives: outside of agriculture, both federal and state laws make it difficult to legally form a cooperative because they are seen as a threat to competition. Capitalism is flustered by cooperation, which it links with collusion and monopolization.

But to answer your question, I am very excited about a union/cooperative in Australia, which was brought to my attention thanks to the Melbourne Lobby chapter. The maritime union in association with the Earthworker Cooperative has created the Earthworker Energy Manufacturing Cooperative[5], which makes solar hot water systems, all with the primary goal of raising the bar for workplace rights.

- DJ

-

Instead of the goal of profit maximization, the goal should be maximization of worker benefits, number of jobs, pay, etc.

- PD

-

…Maximization for doing good in the world.

- DJ

-

For doing good in the world and providing more for workers. I think that is one of the stated agendas of network cooperatives like the Spain’s Mondragon[6] and their mode of expansion, which is to provide and maintain more well-paid jobs and associated education as the key to their mission—as opposed to pure profit.

- PD

-

Correct, but while also recognizing that profit matters. You have to have profit to distribute amongst the workers. When the workers and community are your primary goal, you actually can be successful and do good. This is true with the cooperatives in the Emilia Romagna, the region in Italy where the manufacturing industry coops work with the education coop and with the food distribution coop. The coop network becomes the government at a regional scale, not to mention that they are is one of the wealthiest and most developed regions in Italy.

In terms of architecture, here in Australasia, the cooperative union movement is inspiring. There is also a cooperative network of small firms called ArchiTeam that can offer good lessons. It started out primarily as a consumer co-op where architects can get cheaper insurance by acting together.[7] But this very practical goal has pushed them to have conversations identifying larger issues that have more political and economic agendas, issues that parallel many of those in the Lobby.

- DJ

-

I think this call—for cooperativizing and working with disparate industries with the ambition of influencing regional governance—is crucial. Earlier, you argued that architects have more in common with construction workers than we typically think. This makes me think of the recent book by Jane Hutton, Reciprocal Landscapes, which traces the movements of material (like limestone pavers on Broadway in Manhattan) from extraction, to fabrication, to installation in their urban fabric of New York City.[8] Along the way, Hutton identifies all the people who were responsible for labor associated with these materials. Groups like Who Builds Your Architecture? (WBYA?) try to get a grasp of these processes. To understand a full labor map of architecture and its material assemblies, from design work, to material sourcing, to construction, seems to be the ultimate goal in order to form coalitions with other groups to generate better value propositions, build relationships of trust and equity, and form new systems of mutual support. Also in your talk at The Cooper Union, you mentioned that, “Architects are not constructors, and design is produced by a team.” What is the depth of this team, and do you think that understanding and picking apart this labor map is a good tactic?

- PD

-

I don't think we can ever go too deep, meaning, we should ultimately understand the context in which all the workers live and how those left at home contribute to the work force, and how the materials we extract are part of a larger longer history than we want to know. Everything that Hutton indicates is essential knowledge and promotes what I think is the most important for architects to recognize: that we are within this vast network of material production; that if we want to be influential on the one hand and respected on the other, we need to understand that chain. The respect part, I don't need to explain to you. Every player on that chain dismisses us for thinking that that chain doesn't matter. So, we have to prove that we care, for one, and then we have to act on that knowledge. The influential part follows from the respect part.

- DJ

-

Can you give us a definition of autonomy?

- PD

-

Architectural autonomy is the idea that we, as a discipline, have our own history and our own concerns. Autonomy states that to really be an architect, we have to understand the particular uniqueness of our stylistic history, our institutions, our precedents, our masters. From why changes in style happen, to ideas about form as the essential language, to the different “language” that we architects alone speak—these all are manifestations of a belief in architectural autonomy. Autonomy is the opposite of believing that we are one discipline among many that function within an economy that uses and abuses cultural production.

- DJ

-

So, you are saying that the argument for architectural autonomy contributes to the abuse of the cultural production of architects at the hand of a ruthless economy. How can we address this problem as a discipline?

- PD

-

To see architecture as a function of economic and social conditions; to see changes in these conditions as setting up certain cultural demands that we architects subconsciously as much as consciously must respond to. My book Architecture and Capitalism was my attempt to tell that narrative as opposed to the traditional autonomy narrative.

- DJ

-

Since this issue of Gradient is about “Other Assemblies,” I want to take that as a prompt to ask: how do we re-assemble ourselves—as architects, workers, citizens—and what forms of assembly should we be generating? The Architecture Lobby is one solution to this question, with local chapters made up of workers and students communicating and organizing digitally across space, and executing events and projects collectively. What are the next steps in this process, and what is the end game of building this coalition?

- PD

-

Right now, my thought is that we need to implement the things the Architecture Lobby has been talking about. I feel very strongly that the Lobby should provide concrete benefits. We can only talk about unionization for so long. We can only talk about getting a cooperative network for so long. We can only talk about JustDesign certification for so long. We need to get on with it. I actually think one of the things that would prove that we are walking the walk and not just talking to talk would be finding a case of illegal labor practices, whether unpaid internships, unpaid overtime, or whatever, and bringing a case before the courts. Roe v. Wade didn't just fall into the laps of lawyers willing to take the case: the interested organizations went out of their way to find the right case with the right person for a winnable legal argument. I think we should be doing that.

- DJ

-

But that is not easy to find, right?

- PD

-

Totally. But to get back to your original question, I think you're actually asking what the ideal scenario is for the Lobby. If we were not in America, we could talk about architectural conditions like those found in Sweden, where there is no licensure and the national “professional” architectural organization is a union of architectural employees, one that the government listens to and supports with grants. Here in the US, architects have much less legislative input into the things that shape our economy and our governmental policies. Despite this, I do believe that we can control our own discipline and I think that we should be modeling our ideal society. That means a society that is diverse, that respects labor laws, that collectively supports the value of architectural knowledge in lieu of seeing other firms as the enemy/competition. That means architecture practice that is worker owned, that puts social and environmental ethics in front of job chasing, that listens to the communities we serve, that proves to developers that we, not they, have the long-term maintenance of the built environment foremost in mind. We can only do that if we architects see ourselves as having more to gain by collaborating with each other, and with the other disciplines and trades we work with, than by competing against each other. We can do that. We should do that. Of course, that means we are not talking about the AIA.

- DJ

-

So what does the abolition of AIA look like?

- PD

-

That is a totally good question! Again, this has to do with de-professionalization. I feel that what replaces the AIA can’t just be another professional organization. I actually think the new association would address some of the larger issues mentioned above. It would outline the acceptable role of architects in development; it would outline ethical and sustainable supply chains; it would ensure that architects and not just planners would be involved in infrastructural development; it would support the Green New Deal.

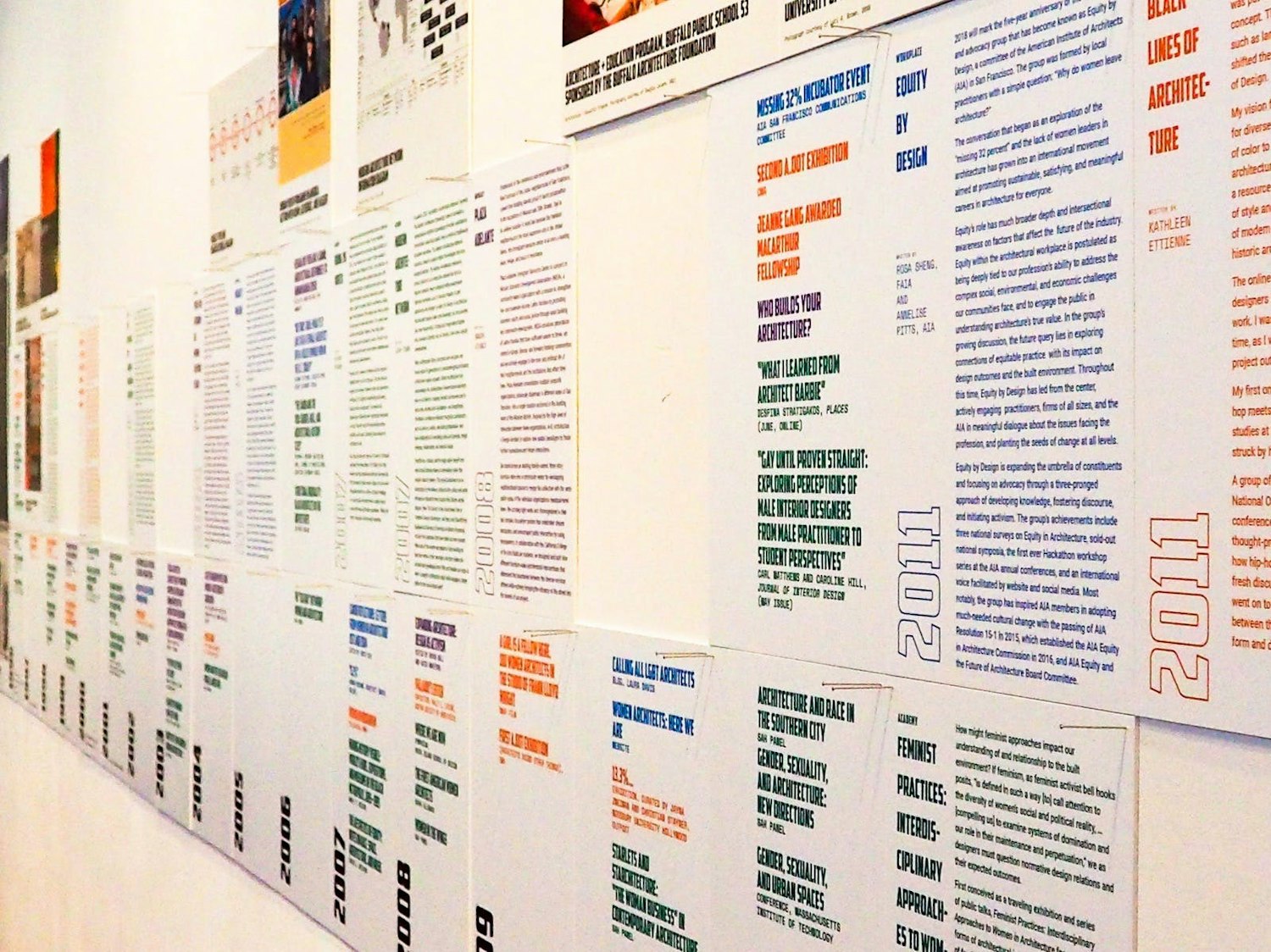

To go back to questions that you had about the academy, it pisses me off that much of this crucial research comes from outside of the academy. It's being done by Who Builds Your Architecture?, The Architecture Lobby, Places Journal, the McHarg Center, or ArchiteXX. For example, ArchiteXX’s Now What?! exhibition foregrounds how activism in our profession has been led predominantly by Black architects and activists. Why don’t we learn this in school?

- DJ

-

Students are demanding this kind of research and content, so there is clearly some miscommunication.

- PD

-

Totally. It's bizarre. This is where people will vote with their feet or vote with their choice of schools. It would be really, really cool if students chose to go to schools that have that larger agenda in mind, where they feel like they can contribute to climate justice, racial justice, economic justice, through an architectural spatial lens, as opposed to selecting an education based on the celebrity status of their faculty.

As an aside, one of my colleagues here in New Zealand made the observation that there's a generation of New Zealand architecture graduates who aren't going to find work because of COVID-19. He recognizes that the New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA) is not going to talk about restructuring the profession, so he has put out a call to academics who are in a position of talking to students about a different kind of preparation and to a profession that should be restructured. It has opened a Pandora's box of all the things that faculty never get to talk about - let alone address. If you open up the opportunity to address what is really happening in the world, architecture students and professors want to be there. They want to be a participant in that discussion.

- DJ

-

Many of the responses to these kinds of questions from the academies seem to revolve around the “entrepreneurialization” of education, where schools are preparing students to enter a panoply of other disciplines, in an attempt to expand the reach and scope of architectural discourse into other territory, like a colonizing force. Do you think that is a good strategy?

- PD

-

I want to say yes and no. It goes back to one of the first workshops that The Architecture Lobby organized, Getting Professional, at the Architectural League, which brought together people who teach professional practice to address the question of whether they teach to the profession we have or the profession that we should have. There were very divergent schools of thought. Some just taught the AIA written rules; others taught a more progressive type of agency. Of the latter, one side said, “They are going to be web designers, stage designers, developers, community organizers. They are going to use their organizational design skills for other disciplines. We should just admit it.” The other side said, “We are training architects. We are not training web designers; we are not training entrepreneurs. We need to train architects that are different than the architects that we have now.” I think I actually agree with the second one, and that the first one is maybe a route to the second one, by indicating that the definition of an “architect” needs to be broader.

[Fig. 6] Now What?! Exhibition

- DJ

-

Right now Taubman College has very active student groups, including The Architecture Lobby chapter, NOMAS, The Initiative for Inclusive Design (IID), among others. They have formed coalitions around Black Lives Matter, the Green New Deal, and the impacts of COVID-19 on their education. Given this context, what do you think is the role of an academic chapter of The Architecture Lobby, and how does it relate to their agency in professional life that will follow?

- PD

-

I think the Michigan chapter is doing amazing work to bring many of the Lobby issues to the studio to address the breadth of labor issues pertaining to design: supply chains, material conditions, carbon footprint, access to skilled and unskilled labor, community engagement, financial power, etc. Student chapters can put pressure on their schools and the faculty, especially those teaching studio, to offer programs and procedures that let students address and design for these issues. Students need to communicate their concerns and not be intimidated by pushback. It helps in this to know that other students, or organizations like the Lobby, have their backs.

The only thing that I could add is to take advantage of all of the knowledge that is within the university outside of architecture. What are the law professors, or engineers, or sociologists doing about these same questions? I think being a university student is a unique condition. Once you graduate, you have less access to such knowledge.

- DJ

-

I couldn’t agree more.

I want to end with a few questions about books and art. What are you reading right now?

- PD

-

I just finished Thomas Piketty's Capital and Ideology (and I did read all of Capital in the 21st Century before that!). If every single American citizen would read Capital and Ideology, we would be a better nation. It goes through all the different ways that the wealthy have created an ideology explaining why they should stay wealthy, and why the unwealthy should stay unwealthy. Piketty is not a Marxist, because he doesn’t believe the Marxist teleology; he believes that at every juncture, those in power have the possibility of being not just fairer, but producing a more stable government. He is stunned by the arguments (ideologies) societies have come up with to justify an obviously bad thing. He also looks at many other non-Western cultures and unpacks different systems and justifications that perpetuate this inequality. It is just an amazing book. Even if you are not politically aligned with him, it's such a good history lesson.

[Fig. 7] Taubman College Snack Break

- DJ

-

Last question: what art/artists are you looking at right now? Why is it important to you?

- PD

-

To be honest, I am not looking at much art here. However, because of the pandemic, I am watching many streamed performances of the MET Opera. The whole opera world has centered around one ridiculous story after another. Yet the stories, in some way, don’t matter. What you see is the love that the performers have for the music, for each other, for the conductor, for the stagehands; and then a love that the audience has for the result. What is great about the streaming performances is that they go backstage. You see how hard the crew works for stage set changes. And when the performers come offstage you see how much they hug each other. When you watch the opera star go from behind stage, where she's happy to be done and beaming, and then switch to seeing her come back onstage, you know this adored performer is a person. At the same time, there is a sense that the whole production ensemble is working together as a team and that they feel so lucky, so happy for it. The audience shares in that warmth. It is so different from how architecture is produced and received.

It makes me think about how well, in other cultural forms, all the workers/contributors are acknowledged. When you listen to a podcasts like Fresh Air, Terry Gross will go on for five minutes listing the people who made that production possible. When we go to a movie, we sit there for 10 minutes watching credits, seeing who the grip is, who the caterer is, etc. And we are paying attention.

Architecture just doesn't have—or doesn’t create—that opportunity. We are impoverished for that.

It is sad for all the architectural workers who go unrecognized, but it is also sad for the public that doesn’t know that so many skilled people contribute to producing our built environment. We all lose.