- Tsz Yan Ng (TN)

-

Hello, my name is Tsz Yan Ng

- Kathy Velikov (KV)

-

I am Kathy Velikov

- Catie Newell (CN)

-

And I’m Catie Newell. We are faculty members at Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning

- TN

-

On September 21, 2021, we organized a remote event titled Material Responsibility, which included pre-recorded interviews with Dana Cupkova, Mollie Claypool, and Achim Menges, followed by a live panel discussion. The theme, Material Responsibility, sought to discuss issues of contemporary material fabrication in context to social, environmental, and construction related challenges. Our provocation comes from a recognition that today, researchers, designers, and builders assume the mantle of responsibility to address inherited legacies in everyday practices. This set of conversations tried to unravel not only assumptions about what and how we build, but also looks to question why we build, and for whom, in order to situate our motivations and impact. Beyond shaping the conversation for this event, we also had a second provocation for our guests on the topic of prototyping. The following text (also recorded as this podcast), expands on that conversation, weaving together common threads and perspectives on the topic of prototyping, as presented by our guests.

- KV

-

The event, and this piece for the online journal Gradient, is organized by the ACDCC group, which stands for the Architectural Computational Design and Construction Cluster. This cohort of Taubman College faculty members are joined by research, teaching, and creative practice that centers on computational design and digital fabrication. For this Gradient drop, under the theme of Bias, we wanted to bring together three guests with varying approaches and perspectives regarding material and computational research.

Knowing that the work and insights from our guests would expand the topics and approaches within the theme of Material Responsibility, we selected researchers whose works place material at the forefront of how they operate in the world. We witness in their works the opportunities found in being attentive to material behaviors and systems, and— perhaps even more importantly—a deep consideration to design approaches that use materials and material processes as a means for architecture to impact the world. This is demonstrated in their practices, ones that embrace material-forward methods of making, community engagement, and ecological entanglements. - CN

-

We’ll begin revisiting these recordings by sharing our guests’ responses to the theme of Material Responsibility. First we will hear from Achim Menges, Architect, Professor and Director of the Institute of Computational Design at Stuttgart University, and listen to his reflection on the urgency of material thinking within the material crisis [Fig. 1]. The second recording is from Mollie Claypool, Co-director of Automated Architecture Labs, and Associate Professor at The Bartlett School of Architecture, who expands upon how we can—and should—live and build with material and social infrastructures. And as an excerpt of our conversation with Dana Cupkova, Co-founder and Director of EPIPHYTE Lab and Associate Professor at the Carnegie Mellon School of Architecture, we’ll listen to her take on the importance of our material works being in attunement with the environment and non-physical aspects of the world, as a means to shape our lives and spaces.

- Achim Menges (AM)

-

Thanks for the invitation to this great and important event. I am very privileged to be part of this conversation. I think it's a very topical theme, mainly because I think that we are facing a situation where we really need to rethink how we deal with the physical aspects of architecture. I think it has become apparent that the physical production of architecture is facing a serious ecological crisis, and this also directly relates, in my eyes, to the way that we intellectually produce architecture. I think it is very interesting to relate this to the notion of responsibility, because on the one hand, I think there is quite an awareness in our discipline that we should at least feel responsible for how we approach this—let's say—material crisis. On the other hand, I think we're quite often also facing the situation that we are lacking the ability to respond. I think that ability has a lot to do with how we create a culture that allows us to find appropriate ways to address this global challenge.

So the way we have tried to approach that over the last decade and a half is by trying to think and build an alternative material culture for architecture [Fig. 2]. We explore how we can actually think about digital technologies—not as a facilitative means of extending existing approaches towards design and construction, or, as I said before, the physical and intellectual production of architecture—but how we can take them as a point of origin for rethinking [Fig. 3].

[Fig. 2]. Maison Fibre. Robotically fabricated lightweight composite structure. ICD, Institute for Computational Design and Construction, IntCDC – University of Stuttgart, A. Menges, ITKE Institute of Building Structures and Structural Design, IntCDC – University of Stuttgart, J. Knippers, N. Früh, M. G. Pérez, R. La Magna.

[Fig. 3] ivMatS Pavilion, Botantic Garden Freiburg, 2011: Institute for Building Structures and Structural Design, Prof. J. Knippers; Cluster of Excellence INTCDC, University of Stuttgart; Cluster of Excellence livMatS, University of Freiburg.

- Mollie Claypool (MC)

-

Thanks so much for having me. I run a research lab at the Bartlett School of Architecture at UCL called Automated Architecture Labs, and we also have a spinout company called Automated Architecture or AUAR for short. So one of the ways that I think about material responsibility, and the way that it's wrapped up in AUAR, is really bound up in a couple of key questions, like, how do we want to live? How can we live better? And when we think about how we want to live and how we can live better, I think it's really important to think about how can we design and build better [Fig. 4]? The built environment is really, intrinsically, tied to these questions, because it provides so much of the material infrastructure of our world.

What we like to do in our work is not just think about this material infrastructure, but think about how the production of that infrastructure is also a social and technological infrastructure.

[Fig. 4] The Block West parts designed by AUAR were manufactured in community-based digital fabrication space KWMC The Factory, using a computer numerical controlled machine. A crew of local people assembled the blocks into the pavilion in under 10 days in September 2020. © Image: NAARO

[Fig. 5] Block West is made from Block Type A, a modular building system designed by AUAR. Block Type A uses a fixed set of Lego-like lightweight plywood building blocks that can be reconfigured into different designs over time without the need for specialised tools or expertise. © Image: NAARO

I'm really interested in how material responsibility transcends the kind of material-ness of the world, to also include these social and technological questions.

-

One of the things that we do in AUAR is really to think about the implications or the consequences of how we want to build and how we want to design, or how we are building, or how we have built, and designed on architectural production. And really thinking about how new technologies begin to have some kinds of implications for the way that we might build or the way that we might produce the world. The way that we might envision it as well. So I'm really interested in automation, as you can probably imagine. And I'm thinking about how we can really utilize new ways of thinking about automation to transform these social practices and all of these building cultures [Fig. 5].

- Dana Cupkova (DC)

-

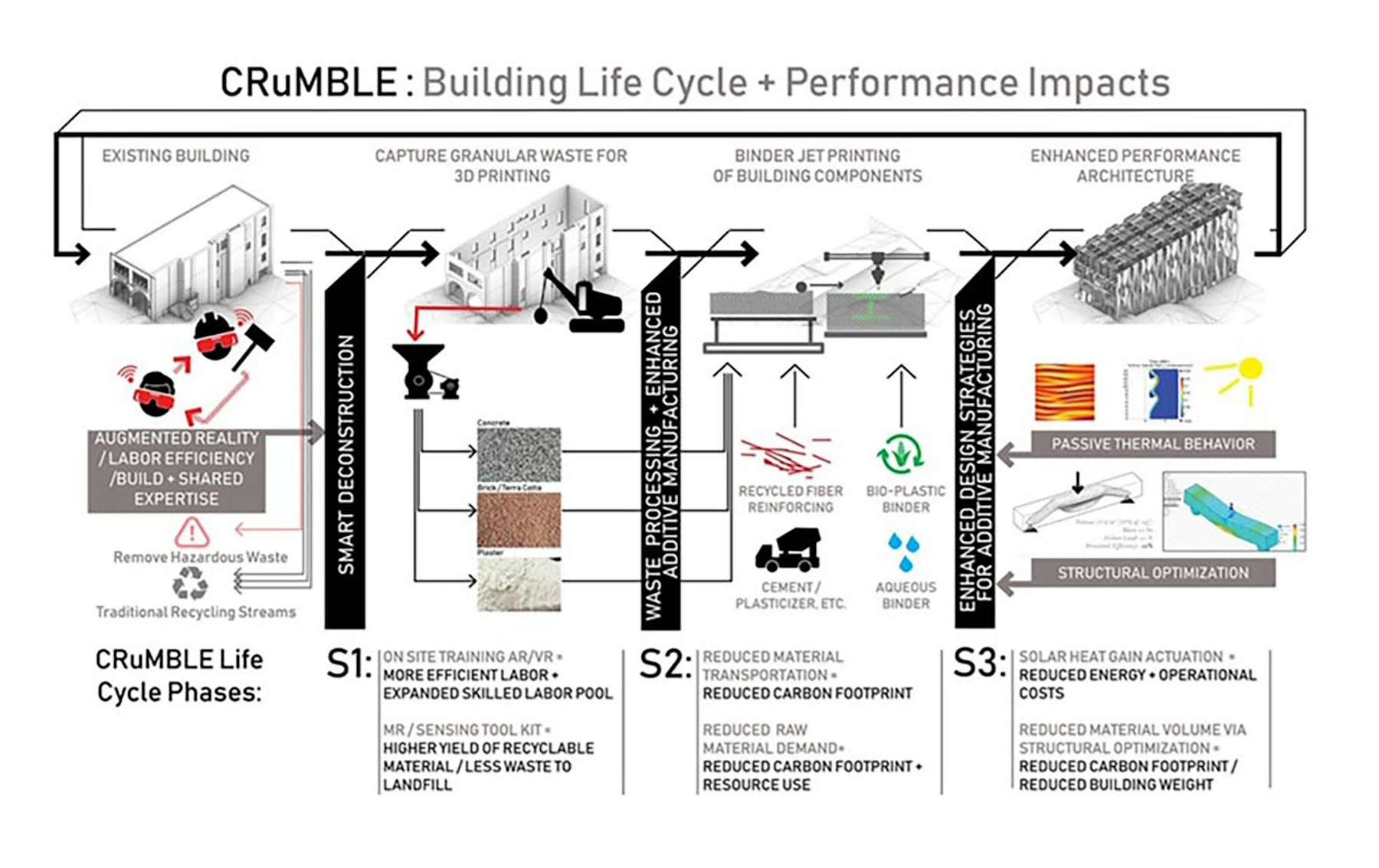

Thank you for having me. I'd like to position Material Responsibility, the call of this panel, within the entanglements of architectural materials and the large-scale ecologies that creates cross-scale relationships, as we rely on industrialized manufacturing and the extraction of resources. I'd like to offer some modest cues into how shaping architectural materials within cradle-to-cradle frameworks can support environmental stewardship [Fig. 6]. This is essentially a case for architecture as a biotechnological construct.It's also a case for computation and manufacturing as new forms of attunement or knowledge frameworks; ones that can support environmental empathy, and lead to more diverse aesthetics and paradigms for the redistribution of resources and labor, positioning architecture as a vehicle for ecological and communal restoration.

[Fig. 6] CRuMBLE: Concrete Rubble Manufacturing for Building Life-cycle and Environment, cradle-to-cradle design research frameworks for ecological architecture manufactured directly out of construction waste and earthen materials proposing to create new pathways for direct non-toxic chemical activation using binder-jet printing. (PI: Dana Cupkova, Josh Bard, co-PI: Robert Heard, Research Associate: Matthew Huber). Research funded by Manufacturing Futures Initiative and Pennsylvania Manufacturing Program. © Image: Dana Cupkova

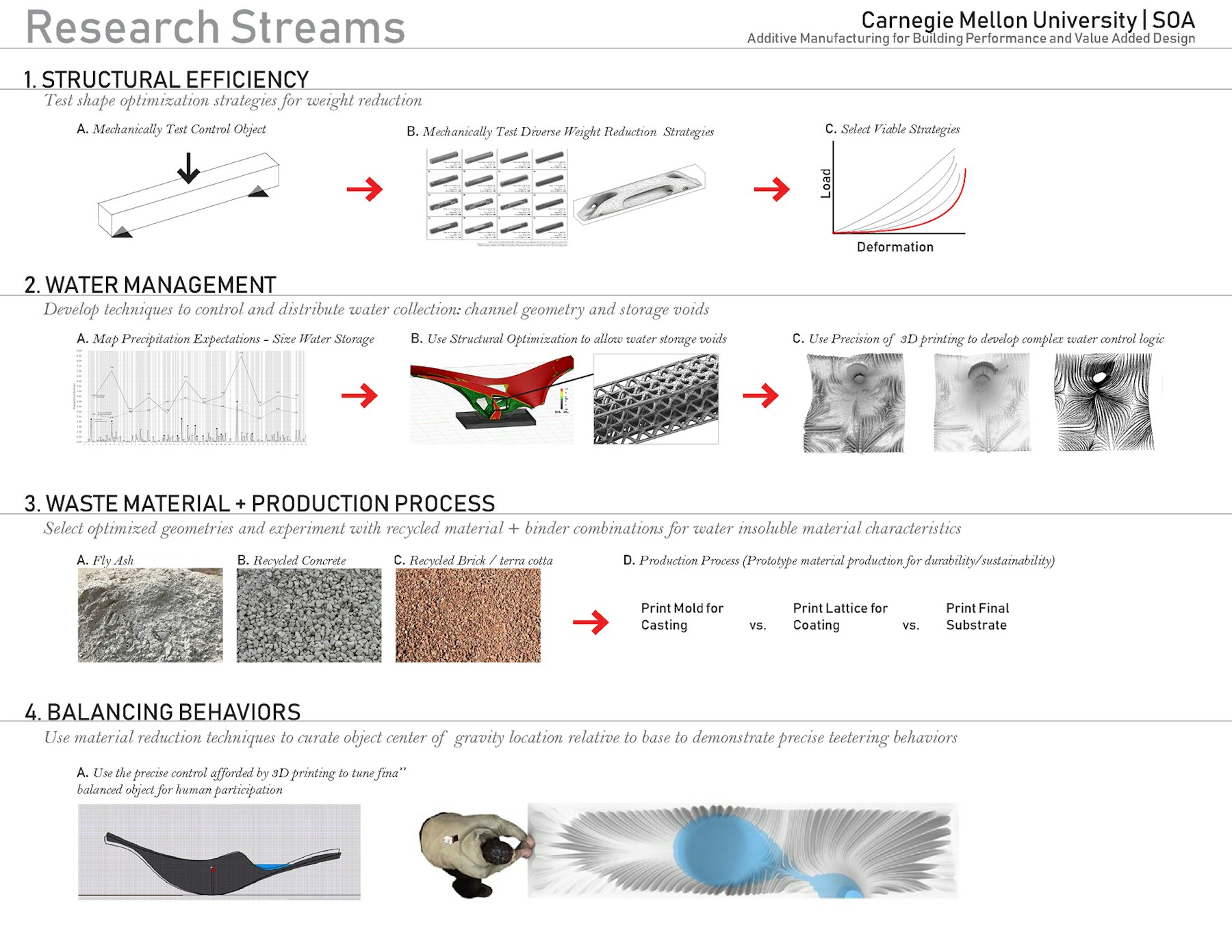

[Fig. 7] CRuMBLE Research Streams: combining across-scales strategies linking structural efficiency , with local landscape operations of water management, pollution patters and to waste-stream material upcycling relative to the embodied energy and CO2 impact in effort to better understand the shape factor that reduces the material volume but increases the strength of architectural components. violence enacted onto the landscape through the actions of gentrification and pollution. © Image: Dana Cupkova

-

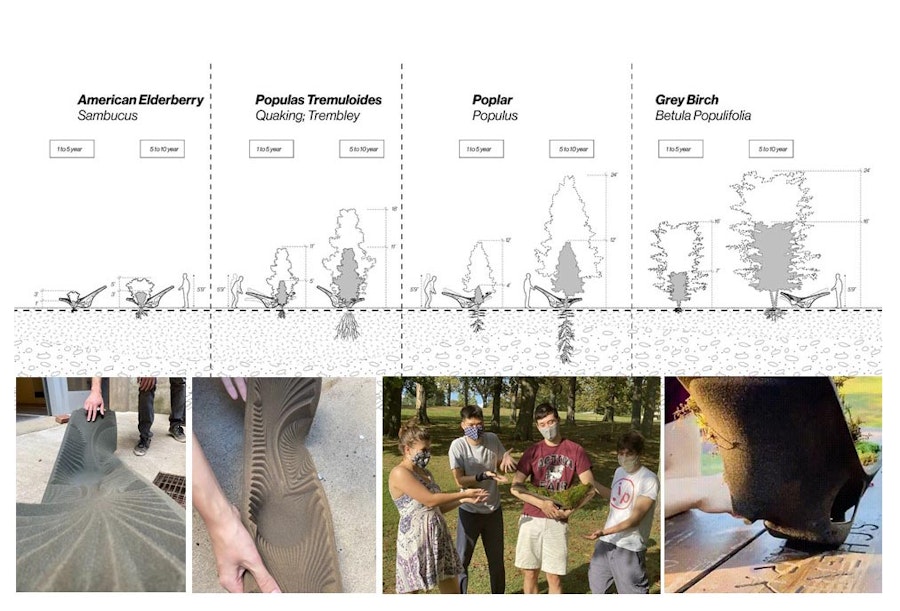

The cycle of nature's violence has always been a part of human history. But the era of the Anthropocene acutely accentuates the ecological imbalance between the mythological harmony of nature and its evolving brutality. As of 2020, humanity officially became the maker of the planet. According to the recent research published in Scientific American, synthetic objects made by humans outweighed the living biomass of the planet (with the radical decline, a planet biomass specifically). This reality mainly comes from the deterministic solution to an approach of materialist design thinking that emerged from the industrial era, its inherent relationship to our design and production tools, and its transactional approach to carbon capture, based in inequities of neoliberal capital. While the design industry is a complicit agent in the formation of this ossified garden in which waste streams become our new anthropogenic nature, emphasizing the need for a deeper biotechnological approach to architectural materials will be central to new forms of its connectedness relative to climate change [Fig. 7–9].

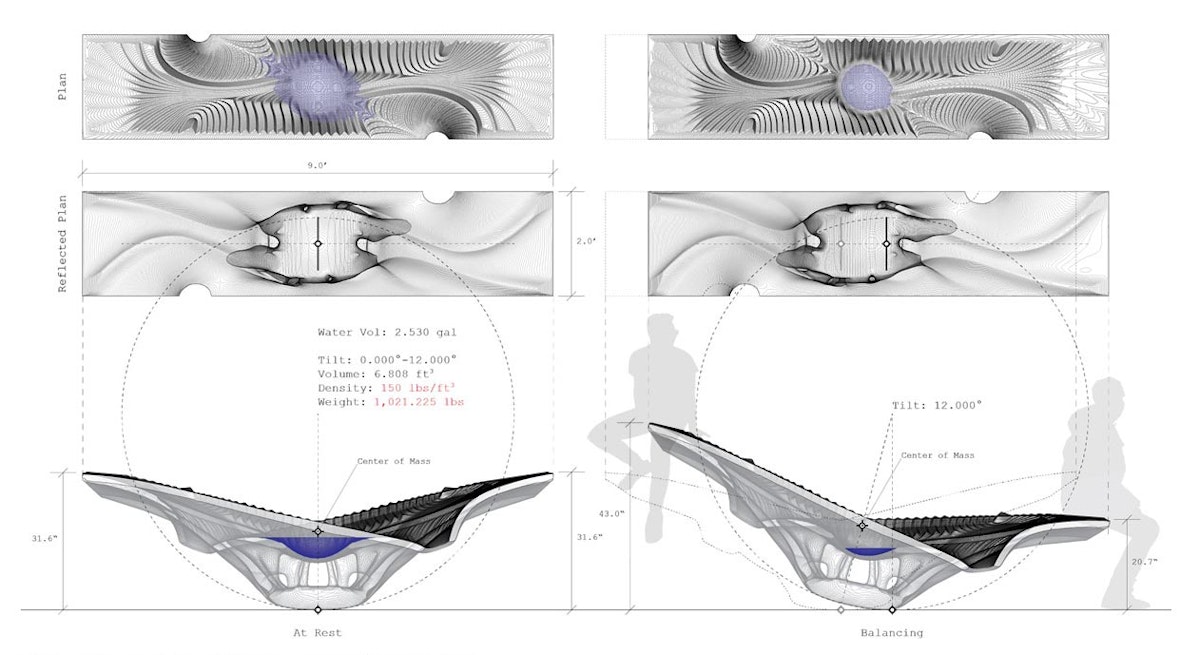

[Fig. 8] Planter-rocker variations: 3 types of rocking morphologies that are balanced and shaped to support interactions between humans and plants, humans and soil, humans and water and would become a substrate for the voice to the environmnent. The cradle is a literal and figurative device for fostering environmental stewardship within a paradigm of urban play that is inclusive in its development and eventually inclusive in its function for both human users and vegetative life. Rocking Cradle proposes an installation that conceives of a nursery as a community space. In the nursery, the cradling vessels intent to draw new awareness between nurture and play, yet carrying those traces of violence enacted onto the landscape through the actions of gentrification and pollution.

[Fig. 9] Rocking Cradle across scales prototyping process: Rocking Cradle acknowledges that it has no origin in new matter. Arising anew from this anthropogenic, ossified landscape as a product of our industrialization, it nurtures potential futures within its corporeal past, marking historical traces of its territory within a new development and fertilizing ecologies within its body. Rocking Cradle is a material prototype rooted in ongoing material-technology research\that proposes a novel cradle-to-cradle design processes are linked to the site’s history of development and pollution patterns deeply-rooted in its current environmental conditions. © Image: Dana Cupkova

- KV

-

In the responses to the provocation of Material Responsibility by Achim, Dana, and Mollie, I think we heard three positions that all, in a way, turn the traditional role of the architect on its head. By that, I mean the traditional role, which began to be defined in the Renaissance by Alberti, of the architect as an expert who conceives of, designs, and produces drawings of a building or structure, but who is ultimately disconnected from its construction and material production.

- TN

-

As all three panelists have described, the current conditions of environmental and social crises are changing the game here. The impacts that almost two centuries of industrial and capitalist production and material extraction related to the built environment have had, on the planet and on society, really compel architects to rethink this traditional relationship; to begin to care for and rethink the material production of buildings—not only their material constituencies and their construction processes, but also the social that is constructed around and through these processes.

- CN

-

It’s really a relatively new territory for architectural design, to rework and reshape the entire material culture of architecture, and to do this from the inside, rather than from the outside. A term that often comes up around the work of material experimentation is “prototyping”: the production of a “proto”, “first”, or “beta” object—one that operates heuristically, that tests hypotheses, and at the same time physically demonstrates something.

- TN

-

Prototyping has often been associated with techno-positive, neoliberal and capitalist forms of production; it is often about product development of the latest and greatest, like phones and cars. More recently, advanced technology for construction, like digital fabrication, is linked with new modes of architectural production as a form of manufacturing. New material and new technologies spawn new designs as prototypes. But at the same time, we are grappling with a changing discipline, one that must account for the changing attitudes towards the environment and our engagement with it.

- CN

-

For the next part of the discussion, we've asked our guests to discuss how they approach the questions of prototyping and the prototype, relative to their work, and also the intentions and values they ascribe to that practice.

In response to this question, we will hear first from Dana, then Achim, and then Mollie.

[Fig. 10] “Rocking Cradle: Interactive Urban Furniture for Environmental Attunement”, a vessel that acts as nursery planter for nascent seedlings, teeter-totter that provokes play, and mechanism for promoting stewardship between a community and its urban biome. The cradles are urban furniture 3-d printed out of granular material that collect water, rock back and forth, provide seating, and inspire the imagination. Shown here is a half scale prototype in testing phase. Project was developed in collaboration with the Center of Life and Arts Excursion Unlimited and will be installed in Hazelwood, PA nursery urban park. © Image: Dana Cupkova

- DC

-

I think that “prototyping” is a tricky word for me. I'd like to use the word “shaping.“ Because shaping refers not just to producing shapes, but also to producing impacts, having a relationship with things, having imprints towards matter and non-physical things, having shaped one's life and the community around you. There's this implication of ecology as a kind of a political system that really forefronts some of the problems with our contemporary industrial production—that has shaped societies—and in a very particular way [Fig. 10]. And especially coming from my background growing up during Communism, which has a sort of centered-ness around top-down production, I think this form of technology allows for different forms of shaping, for distributed models that potentially allow for much more direct imprints of our lives, thoughts, and differences on the objects that we shape or create around us.

- AM

-

I tend to answer in a very straightforward manner: what we're trying to do is not prototyping, but a kind of proto-architecture. But I'm also no longer sure that that's really the right way of relating to it. I also think that, let's say, the uniqueness of buildings, the notion of building systems, how do building systems relate to building designs—I think this definitely also requires a more differentiated discourse, which is also something that we're trying to engage in. Because we’ve found that, for example, this notion of material computation—or this sort of trying to build a material culture—also needs to address those aspects, because quite often it's not entirely clear on what level you engage—on the proto-typical, on the proto-architecture, or on the actually architectural? So I would refer to our buildings not as prototypes. I think they are vehicles of exploration, while being at the same time a kind of architecture that, of course, does not respond to the full scope of complexity that other kinds of architecture need to respond to. But I think that, by no means, results in less architectural value [Fig. 11].

[Fig. 11] Robotically wound truss fabrication. © Image: Achim Menges

- MC

-

I think that prototyping, for us, has provided an opportunity to make tangible some of the ideas that we're talking about. So we're not just talking about the physical prototype, the output, the physical output,we're talking about the prototype as a cross-process. And actually the process is much more important than the physical prototype. People, architects love the physical prototype, because it's something that we can look at and understand, but what often times doesn't get displayed is all of the process, and that's where the most amount of learning has happened.

And so we're prototyping a process more than the physical thing. And we're prototyping a new way of interacting, a new way of rethinking power structures and power dynamics. We’re prototyping “how does it work when you bring in people who wouldn't normally participate in this process? How does it work when you're brought into a process that you normally wouldn't be a part of?" So we're trying to test that out, and that —for us—is the main focus of what we're trying to do, on one side. The other side is purely a technical investigation: really trying to understand how all of the learning about that process and that testing informs and transforms the thing itself. Other ways that we do it are not just in terms of the automating of the “block,” for example, we do it through the prototyping of software.

-

So one of the things that we were forced to do really quickly at the start of the pandemic, when we were about to start the Block West projects, is we were forced to go online with, you know, 10 people who we'd hired to be part of this project, who had never participated in a design project before, and who maybe didn't have a laptop, or didn't know what design software was. How do we still provide access to design when you're not physically in a space? How do we do that in a way that doesn't completely mean that they can't participate anymore? So we had to prototype very quickly, with some really rudimentary software tools that we developed. And that has been hugely influenced by working with people who have not had access to these tools before, and who have slowly informed us and co-designed with us what the tool might look like, and how it works, why it needs to work, where it needs to work better, where it needs to become more accessible. What are the parts of that software tool that are irrelevant for them? What are the things that are really, really necessary for them? And so that, again, is a process of prototyping that we’re going through too.

And we've realized that some of the design softwares that we’ve worked with, or that we’ve developed, people don't want to use. They actually want to use their hands [Fig. 12]. So how do we deliver that? How do we still create an opportunity—design an opportunity—for people to participate in a process of automating and pre-fabrication—in the process of designing a garden studio, in the process of designing a community hub—in a way that doesn't take away from their experience?

-

So one of the ways that we've done this is we've prototyped these “HomeKits.” In the middle of the pandemic, we hand-delivered these kits to their doors, and everyone opened them together, online. And we tried to really think about, how do we learn from all of these different ways of testing and providing people the opportunity to participate? And it was also an opportunity for us to really understand what doesn't work, even though we had an assumption that it would, and to really question where our own biases are coming from in that process, too. And we have a lot of them that we need to unravel because we've been told we're been experts for our entire careers, and we are not experts in these communities. The people who live there are experts in their own communities.

[Fig. 12] Block West was designed by local residents using AUAR’s app, following a series of online workshops during lockdown. Block West, showcases adaptable building systems and people-friendly technology that can help communities collaborate to create the homes they need. © Image: Ibi Feher.

- KV

-

What is interesting about the work that Dana, Achim, and Mollie all do—and the way they discuss the question of material prototyping—is that it seems to respond to these complex, often globalized, ecosystems of material production through situated, materially-specific, and very human means of intervening in these complex systems. Even though all three use technologies extensively, the work thrives in its ability to frame our connections to deeper social, cultural, and environmental communities.

- CN

-

At this moment of defining Material Responsibility, and taking responsibility, it is key to recognize that we must remain attentive to our materials, and our material practices, both in their physical and nonphysical opportunities.

Thank you Dana, Mollie, and Achim for these reflections.