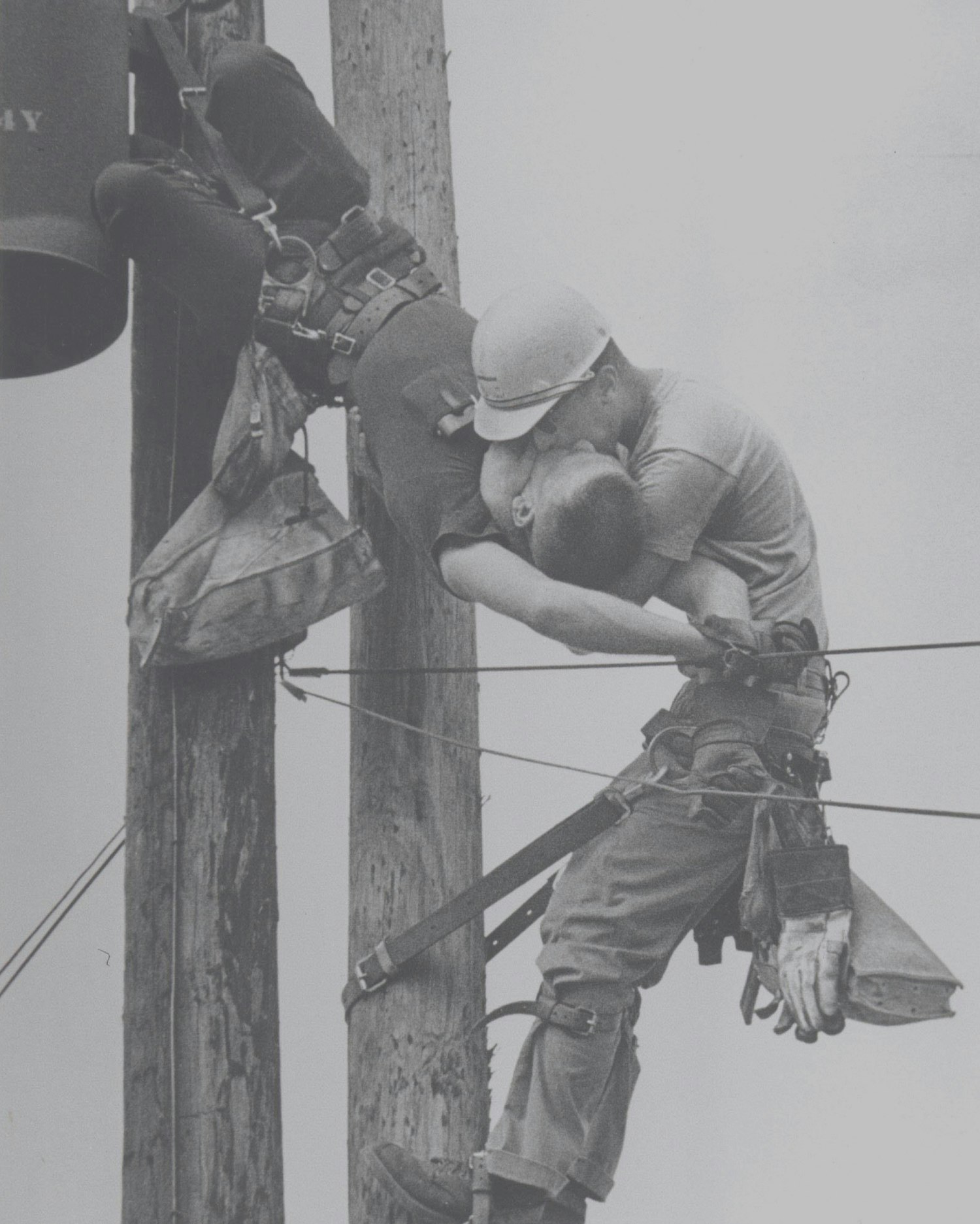

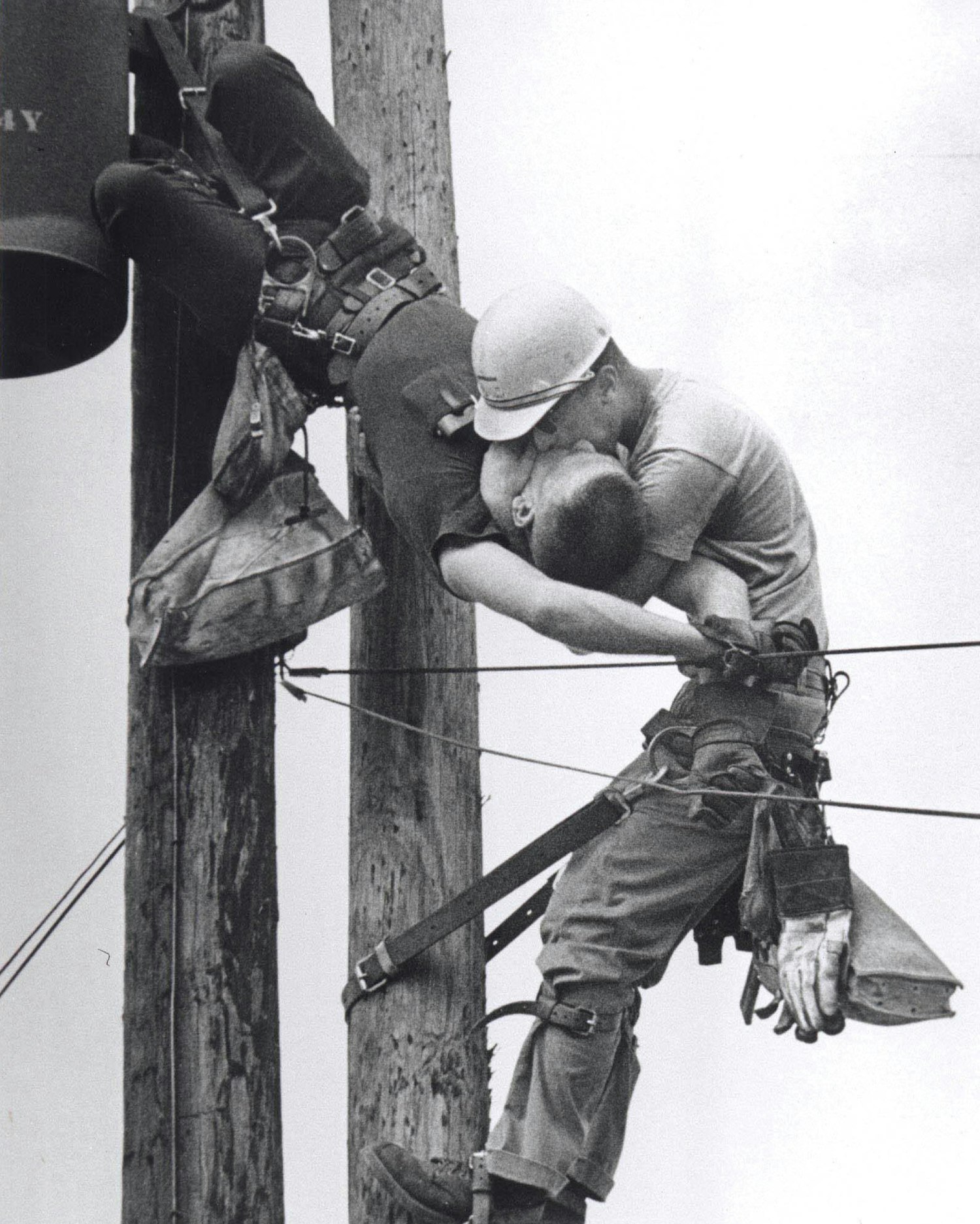

“Kiss of Life,” a Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph, was taken on July 17, 1967 by Rocco Morabito, a staff photographer at the Jacksonville Journal. The black-and-white image features Randall Champion and Jim Thompson, two apprentice linemen working for the Jacksonville Electric Authority who were helping to restore power to the surrounding area after a statewide need for air conditioning reportedly overwhelmed the electrical grid.[1] Champion had come in contact with a live wire that sent 4,160 volts of electricity through his body, knocking him unconscious. Thompson was the first lineworker to reach Champion, at which point Morabito, who was on assignment to take photos of a nearby railroad strike, called an ambulance and began documenting the scene with his Rolleiflex camera.[2]

Kiss of Life, Rocco Morabito, July 17, 1967 © Wikipedia Commons

The renowned image—one in a series of photographs that Morabito captured that day—is a skillful and timely depiction of benevolence amid danger, evoking the drama and tension of paintings that have been celebrated by art historians. Compositionally, the picture plane is sliced vertically by two wooden poles and horizontally by two electrical wires, one taut and one relaxed. Together, the poles and wires form a right angle that frames the linemen’s faces. Champion is seen on the left dangling upside down from his safety belt, which is strapped to a transformer that converts electricity to different voltages. An insulated copper ground wire that is commonly used to safely direct electricity into the earth, effectively avoiding shocks to both the grid and the body, draws a line down the pole behind him. Two bags presumably filled with relevant tools and supplies hang from Champion’s leather-banded cinched waist. His outstretched arms, crossed, appear to rest delicately on a neutral line as the remainder of his inverted, lifeless body surrenders to gravity. On the right, Thompson perches on the other post with the help of his spiked boots and a climbing belt. He maintains his stance by pulling his hips away from the pole, which keeps the belt in tension.

Much like his fellow lineman, Thompson’s lower half displays job-related gear that helps to transform his slim physique into an infrastructural agent.

The gendered term “lineman” was first used to describe someone who physically worked on overhead lines for the telegraph, a means of communication that emerged in the United States in the 1840s.[3] Though telegraph lines could be stretched between trees, the system’s expansion eventually required men who could efficiently set, climb, and wire poles. These linemen continued to work through the invention and expansion of the telephone system starting in the late 1870s and the rise of electric power during the late 1890s. The New Deal, about forty years later, involved the electrification of rural and remote areas, which led to the hiring of even more powerline technicians. This also led to apprenticeship programs that offered novice linemen, like Thompson and Champion, with standardized training meant to increase competency and mitigate risk. Soon after, the postwar economic boom resulted in the construction of new housing developments that not only needed electricity but additional maintenance crews that were available for emergency repairs. Recounting this history ultimately reminds us that infrastructural growth is always incremental and that the expertise of those responsible for managing these systems is always emergent.[4] This history also helps to contextualize Thompson and Champion’s place within a state-sponsored regime of routine maintenance.

As the demand for reliable electric service increased, so did the incidence of harm. Unlike telegraph and telephone crews, linemen working on power lines were exposed to higher risk of injury or death because of possible electrocution.[5] To alleviate some of this risk, companies began shifting power transmission underground starting in the late 1950s, which resulted in the corresponding worker title “groundman.” This is important to know because when Thompson made his rescue ascent in 1967, he was the closest person to Champion who could climb up the pole since the groundmen below did not have the necessary training or tools to do so.[6] Shared across linemen and groundmen is a willingness to embrace the volatility of electrical infrastructure, which Morabito impressively captured in his photograph.

The photograph also depicts, quite simply, an intimate moment shared between two men. Thompson, who barely knew Champion, is shown physically supporting his coworker’s back with his right arm while using his left arm to cradle Champion’s head, even appearing to gently press his thumb against Champion’s chin in order to better align their faces for respiratory stimulation. A glance at Morabito’s other photos from that day reveals that Thompson had lifted and repositioned Champion’s torso and arms onto the wire so that their mouths could be adequately close for the transmission of air. In an interview decades later, Thompson recalled that Champion’s “cheeks were blue and there was no movement to him.”[7] Upon realizing this, Thompson locks lips with Champion, blows air into his lungs, and strikes his workmate’s chest until he regains consciousness. Thompson went on to say that once Champion was lowered to the ground, “We just held him there for a minute to get him to calm down…We just held onto him…”[8] Infrastructures make relational life possible, and the relationship between these two men—their proximity to one another—was forever reconfigured by a fateful shock.

We tend to not notice infrastructures until they break down, which means that the individuals tasked with repairing these systems only come into public view while performing unpredictable and often dangerous work.

Sociologist Susan Leigh Star asks us to focus on the ordinary people helping to manage and maintain infrastructures “whose work goes unnoticed or is not formally recognized” because certain patterns of sociality would not be possible without their care.[9] Shifting our gaze toward lineworkers and their experiences, for instance, would help us recognize how critical they are to preserving the welfare of society, especially since power outages can be a matter of life and death. Focusing on their impromptu responses to infrastructural failure could also uncover opportunities to rewire the system and its predetermined relations.

Building upon Star’s work, scholar Ara Wilson claims that “understanding how infrastructures enable or hinder intimacy is a conduit to understanding the concrete force of abstract fields of power.”[10] If structures of dominance unfold across diffuse networks, making them harder to recognize, Wilson suggests that we focus on intimate relations as a way of making power more tangible and easier to see. Morabito’s photograph allows us to do so by framing an extraordinary closeness between two otherwise ordinary individuals. We know that the electrification of the U.S. helped to extend political agendas, capitalist values, and modernist aspirations, impacting nearly all aspects of American culture,[11] but examining intimate moments occurring within this infrastructure could open up more nuanced and less reductive ways to perceive collective life.

So, what does this portrayal of intimacy between Thompson and Champion suggest about the world beyond the frame? One observation is that the closeness of Morabito’s photographic subjects and the harrowing circumstances surrounding their intimate encounter exemplify the vulnerability of infrastructure workers, specifically their susceptibility to harm. Here, vulnerability is understood as a weakness, as a state of being that must be avoided at all costs. And if it cannot be avoided, then it must be hidden, which humans achieve by developing facades to appear resilient. In the case of lineworkers, the threat of physical injury due to electric shock leads them to wear insulative clothing, including rubber gloves and boots, for protection. To some extent, the photograph serves as a warning of what could happen if we fail to properly assess the situation and take precautions: we expose ourselves to pain (or worse).

But I offer a different reading of Morabito’s snapshot: here are two ordinary people who accepted vulnerability as a normal part of their lived experience. Upon saving Champion’s life, Thompson immediately resumed work on the line to avoid an incoming storm, as if his courageous actions were merely part of the job, later remarking that he did not consider himself to be a hero.[12] In this regard, vulnerability is not understood as a weakness but as a source of strength, for there is power in the decision to expose oneself to risk. In exchange for this exposure, we open ourselves to care, compassion, and connection. To work on infrastructure is to actively engage the instability of everyday life, and if we accept that all of us live in a vulnerable world, that means that within this instability are many opportunities for social transformation.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that lineworkers should further endanger themselves by shedding their protective armor. Rather, this is an invitation to ask ourselves how the formation of infrastructures could potentially reframe our relationship to our own vulnerability. Would we approach design processes differently if we accept the brokenness of our world as a point of departure? How might architects, for instance, develop environments that center the experiences of maintenance crews or others at the margins who have to grapple with the day-to-day operations of these systems? How might intimacy provide a rubric for understanding uneven materializations of power? In what ways could infrastructures foster unexpected forms of comradery or solidarity? What profound reconfigurations of relational life have yet to be proposed and tested? Closely examining the particular conditions that sustain or constrain interpersonal relationships—that, say, unite two men in a conspicuous lip-locked formation—could help us see our infrastructures anew and imagine alternative formats for coexistence.