Judy Heumann and the Design of Disability Justice

Civil rights protections for Americans with disabilities did not exist until the 1970s, a time when the long held default thinking about disability was still heavily invested in the prevailing paternalistic ‘medical model’ that everyone, even those with disabilities, had little choice but to accept. A common mindset among the disabled (as voiced by Kitty Cone), was “if I thought about why I couldn’t attend a university that was inaccessible, I would have said it was because I couldn’t walk, my own personal problem.”[1] But as American activism emerged in the 60s, so did a more nuanced understanding of the ‘social model’ of disability, defined not so much “by impairment as by the ways in which society - and the designed environment - bolsters and shapes our definition of ability.”[2]

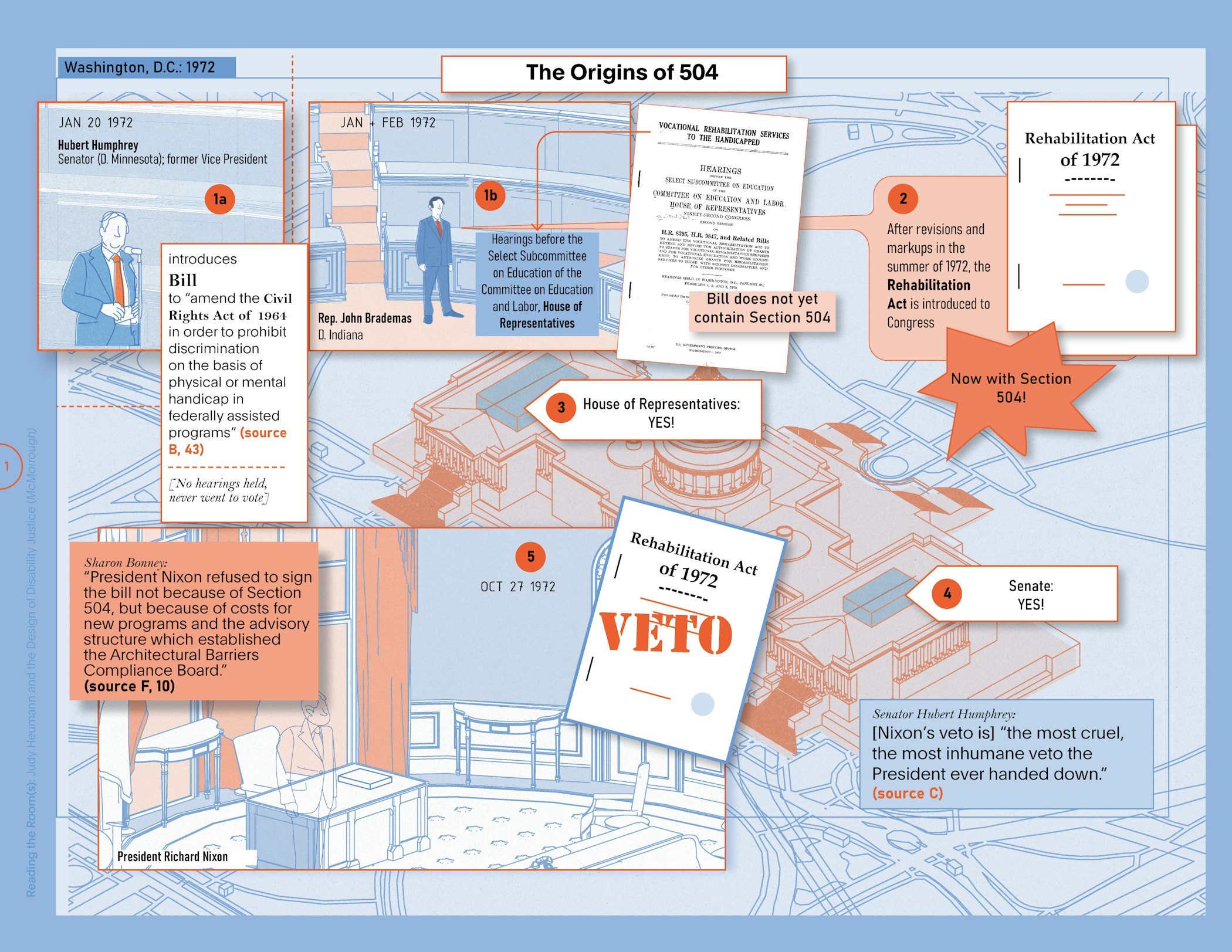

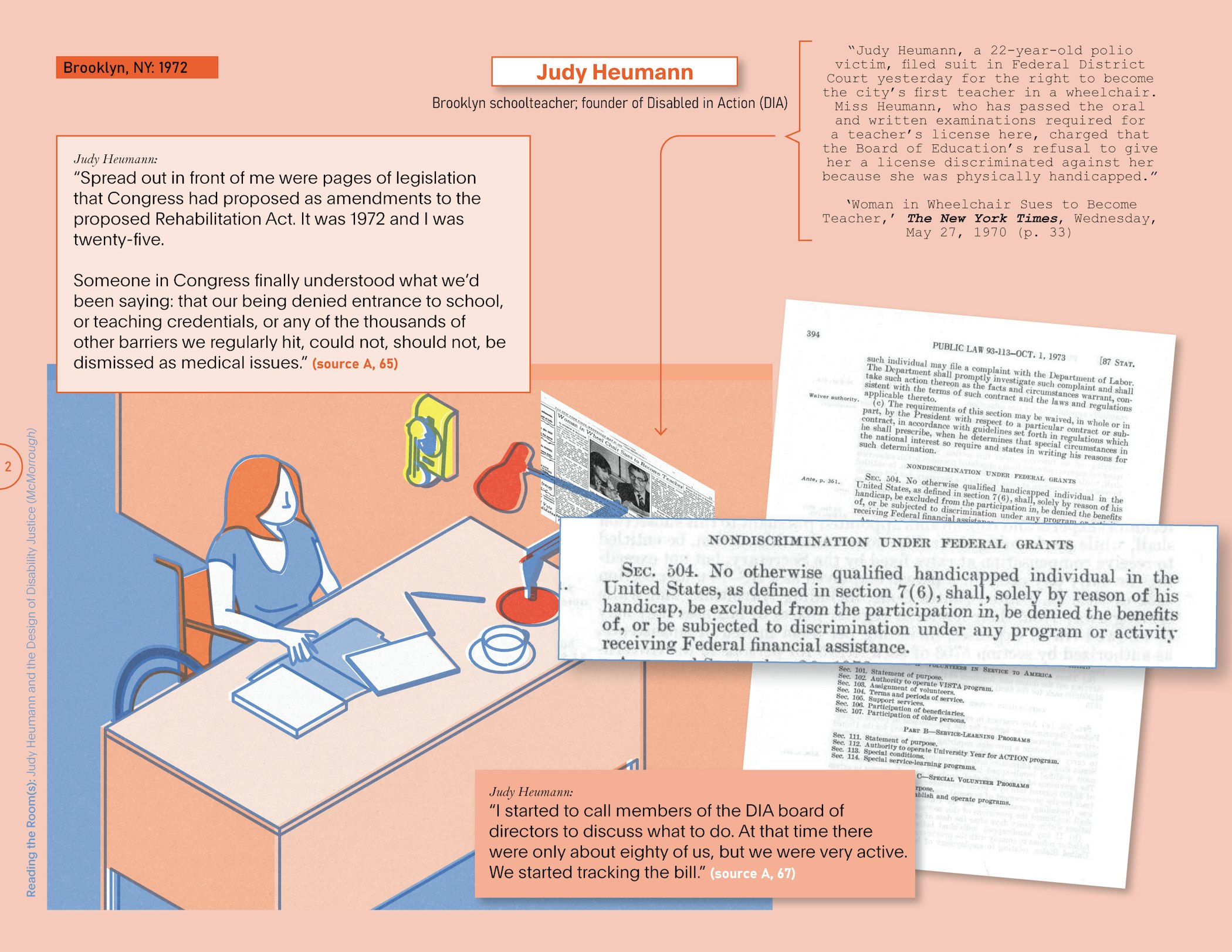

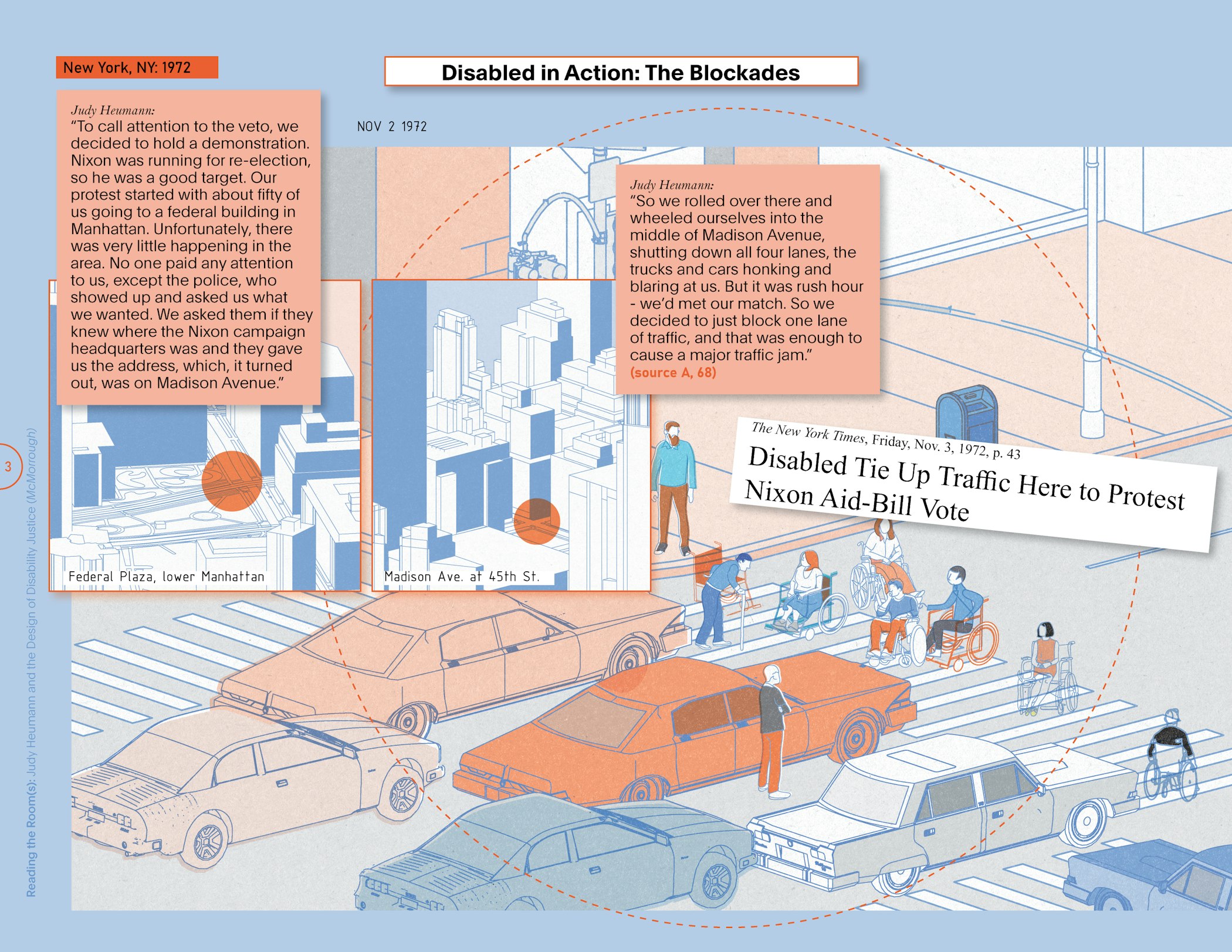

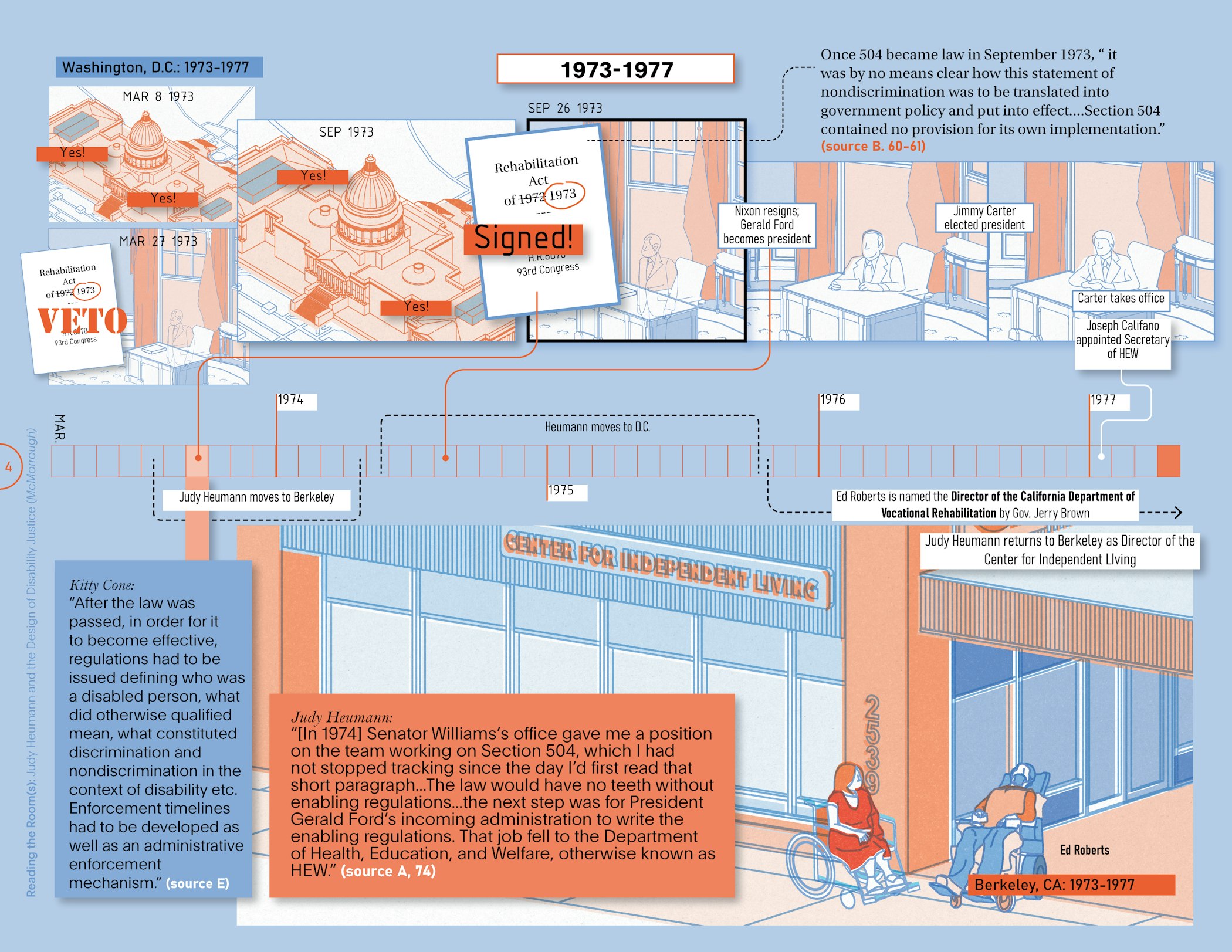

What happened in the 70s began with a somewhat inauspicious moment within a meeting of congressional staffers. While marking up the Rehabilitation Act of 1972 (proposed legislation on vocational rehabilitation aimed “to empower individuals with disabilities to maximize employment, economic self-sufficiency, independence, and inclusion and integration into society”), it was decided that language was needed that would deter anticipated discrimination in employers’ decisions to hire those who had completed vocational rehabilitation training. This modest-seeming addition, under Title V: Miscellaneous, was Section 504, one sentence at the very end: "No otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States, as defined in section 7 (6), shall, solely by reason of his handicap, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Frank Bowe, a founder of the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD) called Section 504 “the single most important civil rights provision ever enacted on behalf of disabled citizens in this country,”[3] though, according to Richard K. Scotch, 504 slipped easily under most lawmakers’ radars. “It appears,” he writes, “that most members of Congress either were unaware that Section 504 was included in the act or saw the section as little more than a platitude, a statement of a desired goal with little potential for causing institutional change.”[4] But to Judy Heumann, a young Brooklyn schoolteacher who had made headlines for successfully suing the NY Board of Education for denying her a teaching license based on her disability, the impact of those 41 words was life changing. She would later learn that they were “the stealthy work of a few of our champion senators who’d asked some of their senior staff to figure out how to quietly insert civil rights provisions”[5] into the Rehabilitation Act, but she was insistent that, “regardless of how Section 504 had come about, we weren’t going to let it go.”[6]

What Heumann and her cohorts did was to channel a hard-won resourcefulness, fueled by a lifetime of compensating for the ignorance and indifference of others. In short, they were observant and inventive: quickly reading each room, patiently marshaling their impatience, and unearthing any possible advantage from endless disadvantages. Through persistent activism that gave disability a visibility that was honest, unfiltered, and very human, they managed to enlighten an oblivious culture, sometimes one person at a time.

Another veto later, and the Rehabilitation Act was finally signed in September 1973. Shortly before that, Heumann, persuaded by Ed Roberts, moved west to pursue a Master’s degree at Berkeley, and to seek a more self-sufficient life through the Center for Independent Living (CIL), which Roberts had founded in 1972. In 1974, New Jersey Senator Harrison Williams, one of Section 504’s ‘champion senators,’ recruited Heumann to his Washington, DC office, and though finally professionally immersed in the future of 504, Heumann’s activism continued unabated. In the lobby of the Washington Hilton, outside the 1974 annual meeting of the President’s Committee on Employment of the Handicapped (PCEH), Judy Heumann and Eunice Fiorito of Disabled in Action held workshops to discuss topics of discrimination not being addressed in the president’s meeting. The group in attendance brought together various other disability-rights organizations into one cross-disability group, officially forming the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD).

For the almost five years that it would take for Section 504 to go from bill to law, Heumann and a deep bench of disabled activists that included Roberts, Bowe, Fiorito, Kitty Cone, and Brad Lomax were instrumental in making it happen - outside of, within, and despite, the constantly changing political machinery and its penchant for continually kicking 504 down the road.

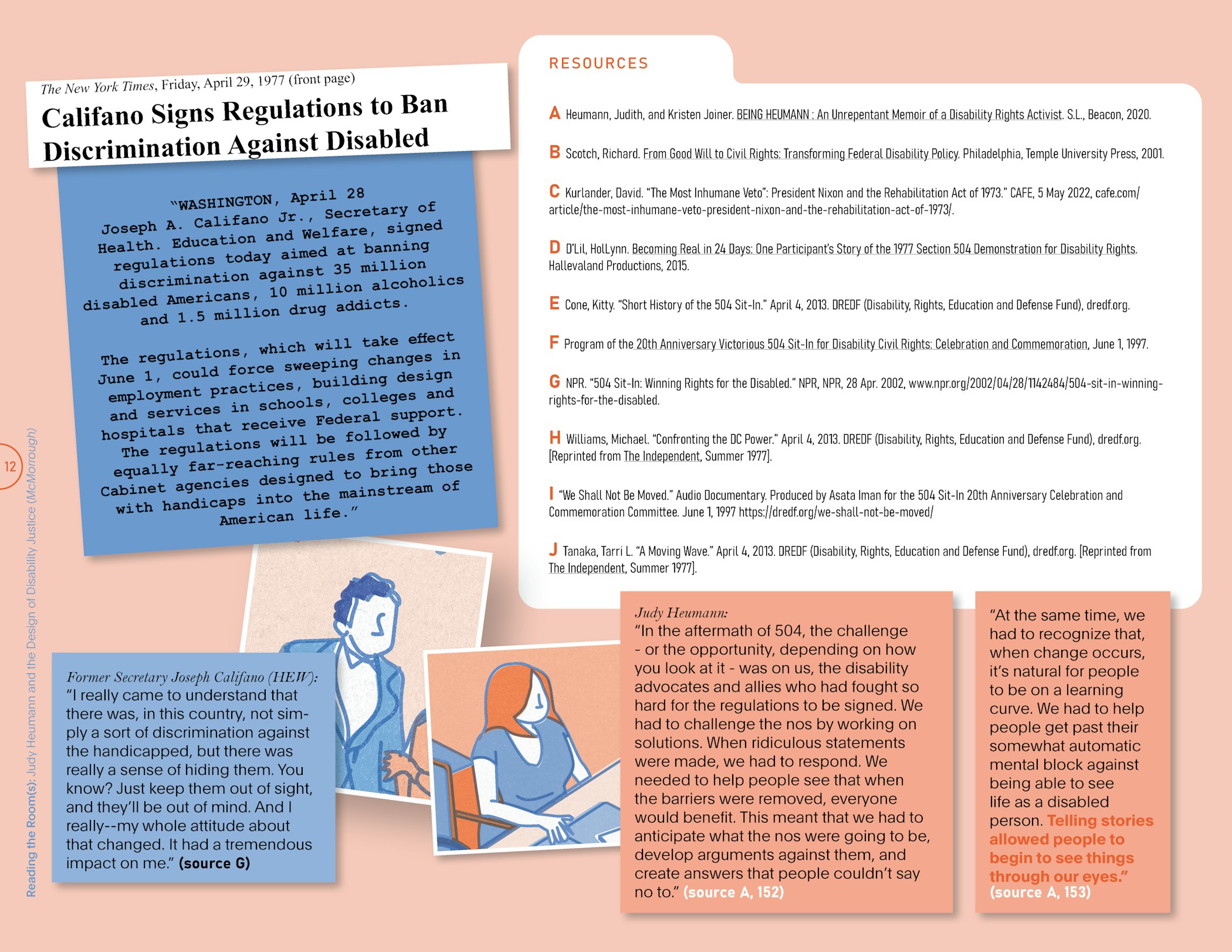

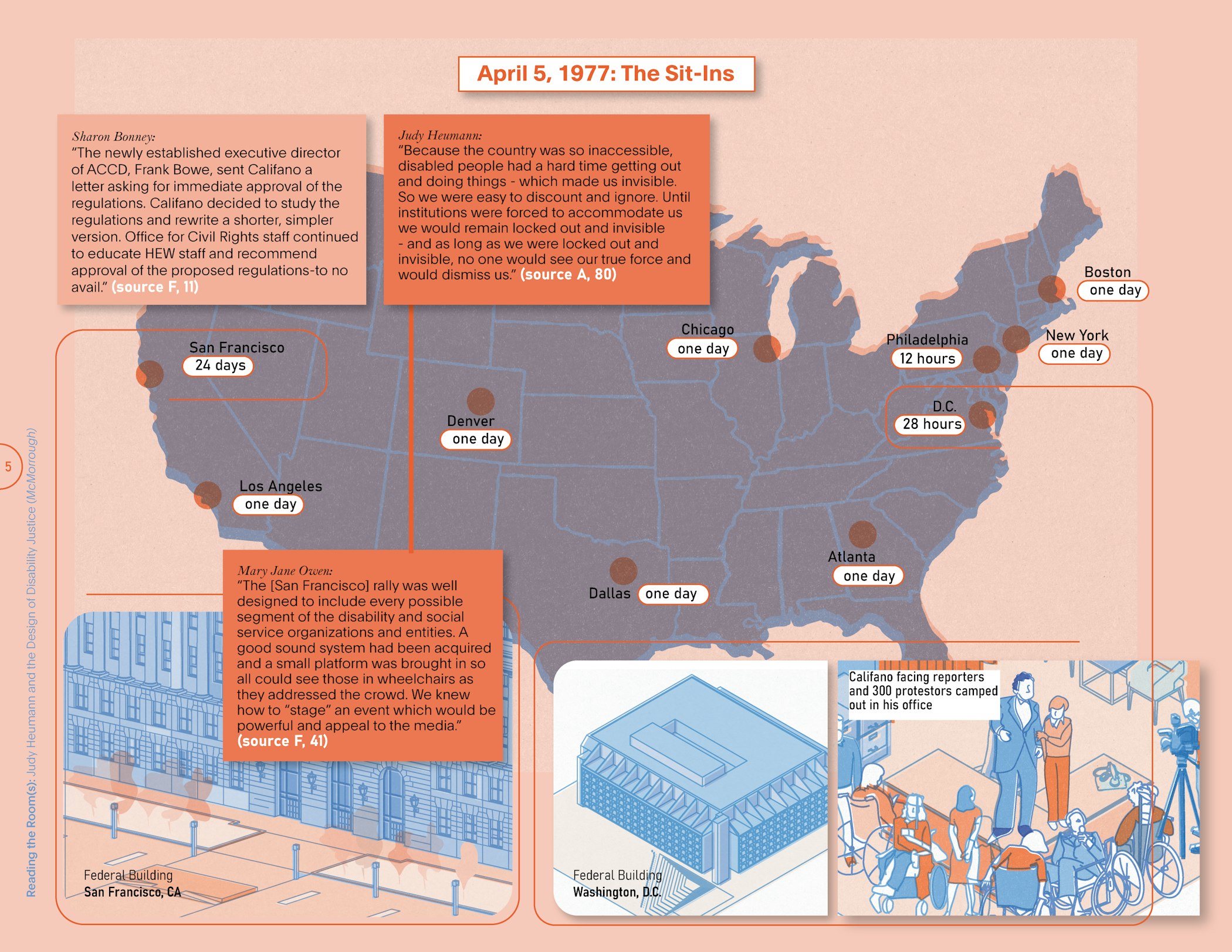

When he came into office with President Jimmy Carter in January 1977, new HEW Secretary Joseph Califano inherited the proposed 504 regulations, which, as April began, remained unsigned. Kitty Cone recalled that “the ACCD, realizing our civil rights protections were being gutted, demanded HEW issue the regulations unchanged by April 4, or action would occur. They called for sit-ins at eight [ten] HEW regional headquarters, on April 5th if HEW didn’t comply.”[7]

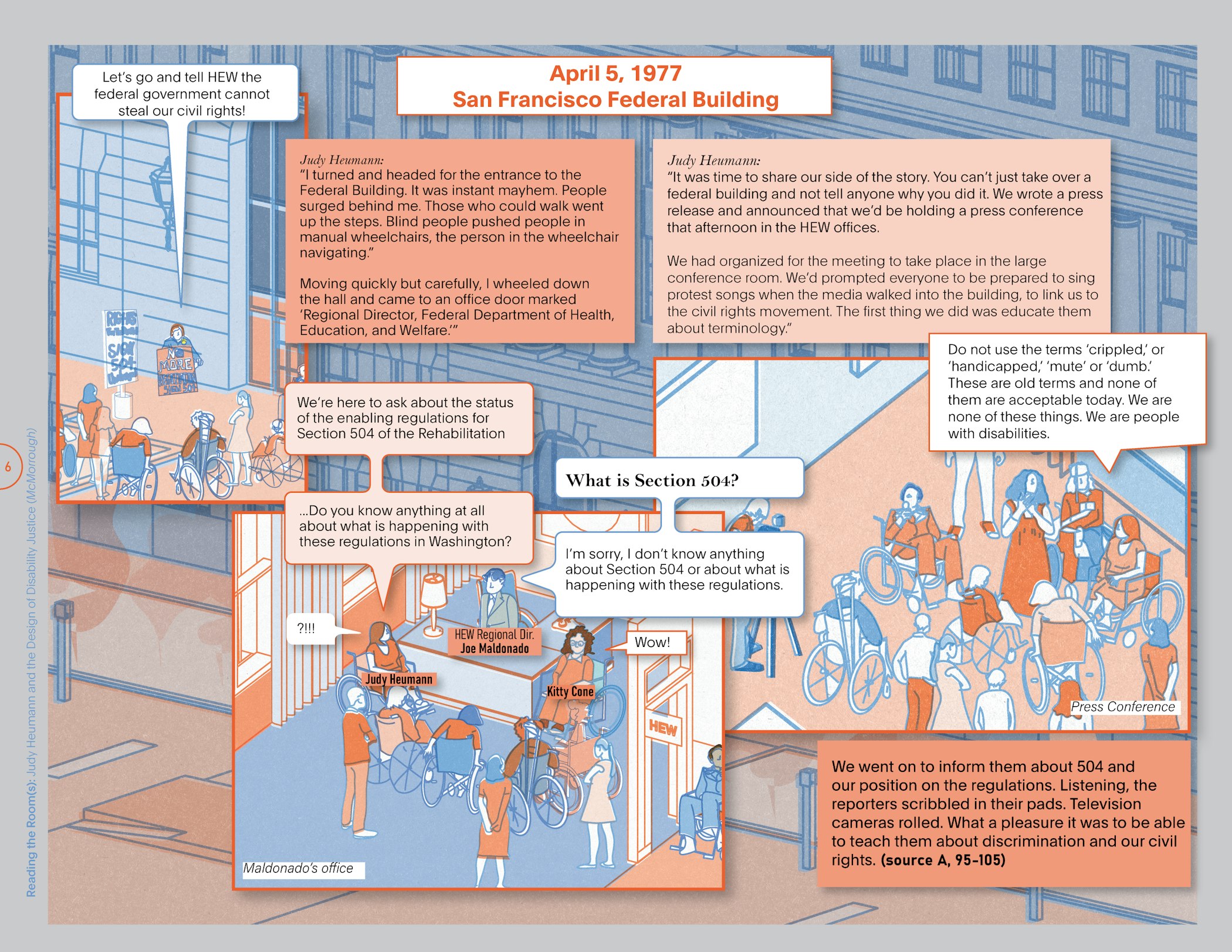

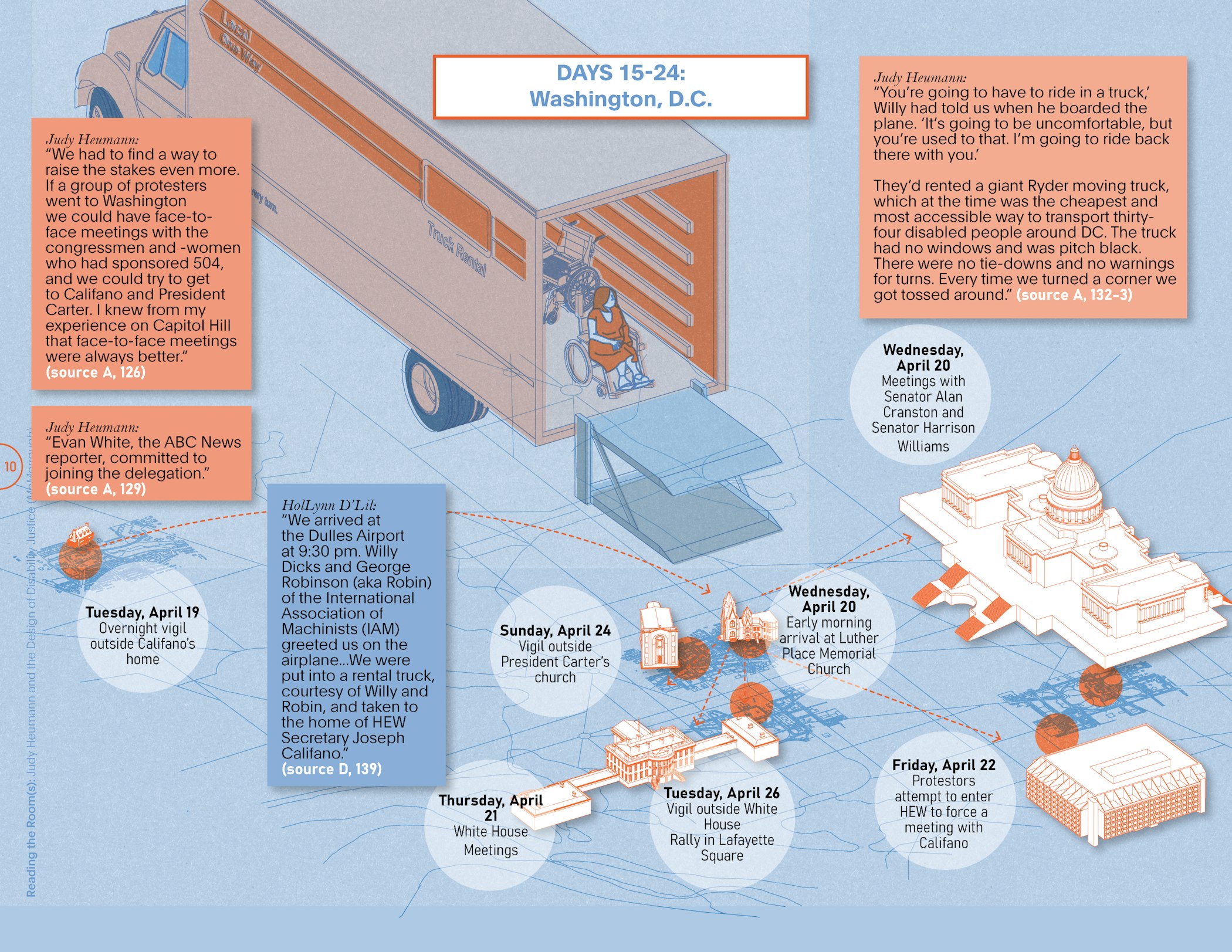

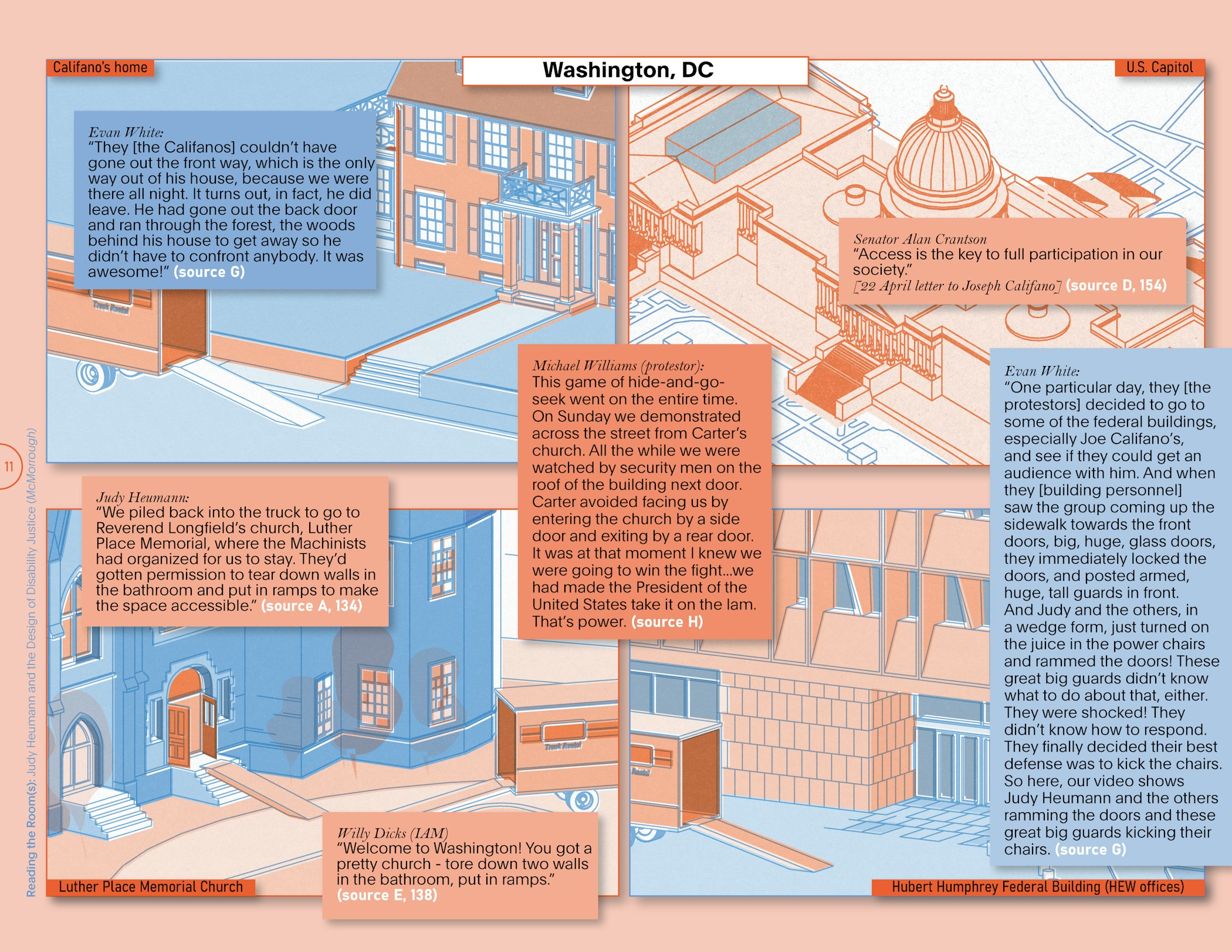

On April 5, in parallel with ACCD members in nine other cities, Heumann, Cone, and hundreds of other disabled activists staged a peaceful rally in the plaza of the San Francisco Federal building (home of the HEW offices). Most of the rallies throughout the country had concluded by day’s end, except in Washington DC, where 300 disabled protestors camped out in Califano’s office, and in San Francisco, where things were just getting started.

The San Francisco rally was a raucous, defiant and joyously inclusive environment full of stirring speeches, heartfelt testimonies, and rousing music. The final speaker was Jeff Moyers, a visually impaired musician who led the crowd in Pete Seeger’s civil rights anthem “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize.” As he finished, Judy Heumann moved her chair to the microphone, waiting a moment for the silence to descend before making the announcement that she and the other organizers had all agreed on: "Let's go and tell HEW the federal government cannot steal our civil rights!” And as she turned and headed to the building’s entrance, the crowd followed her. “It was instant mayhem.”[8]

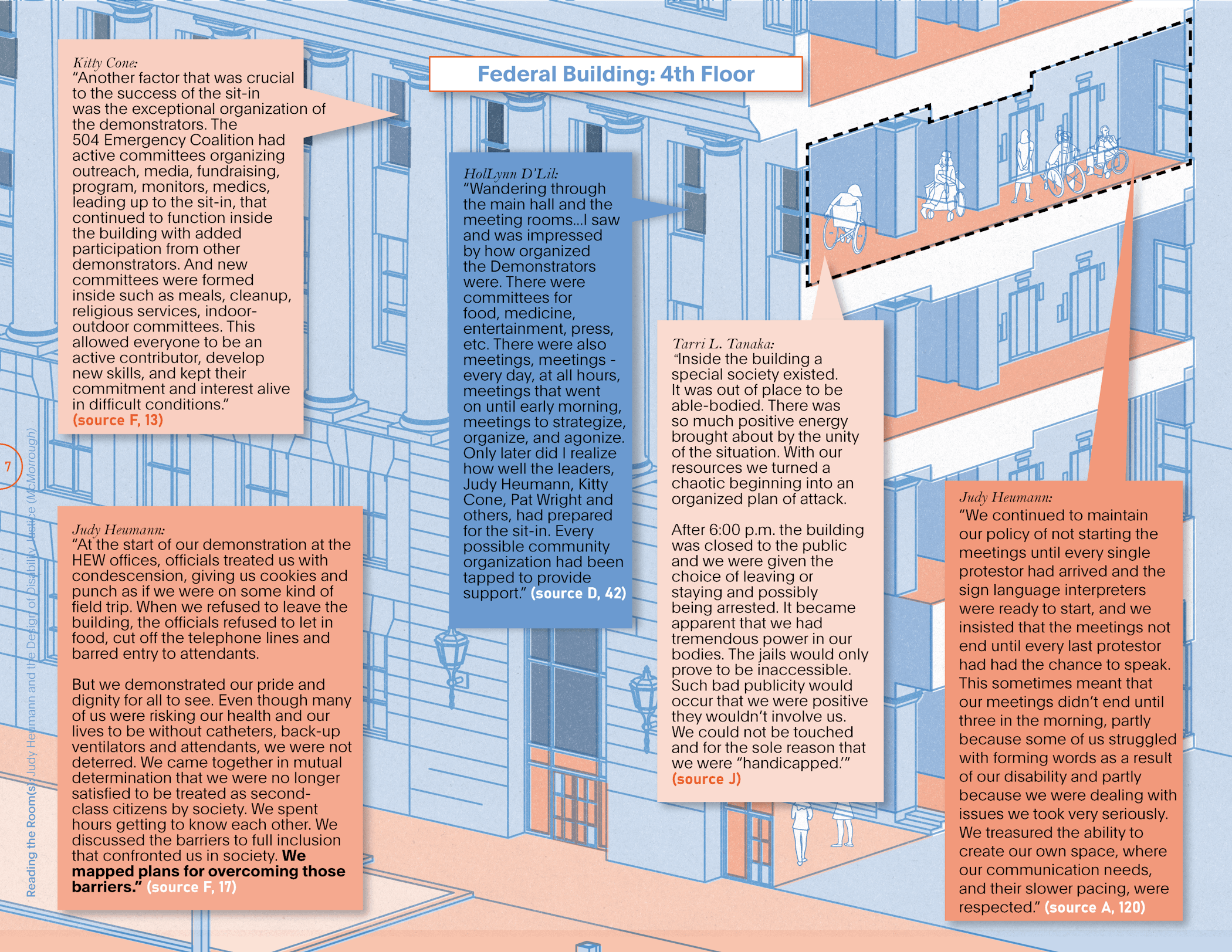

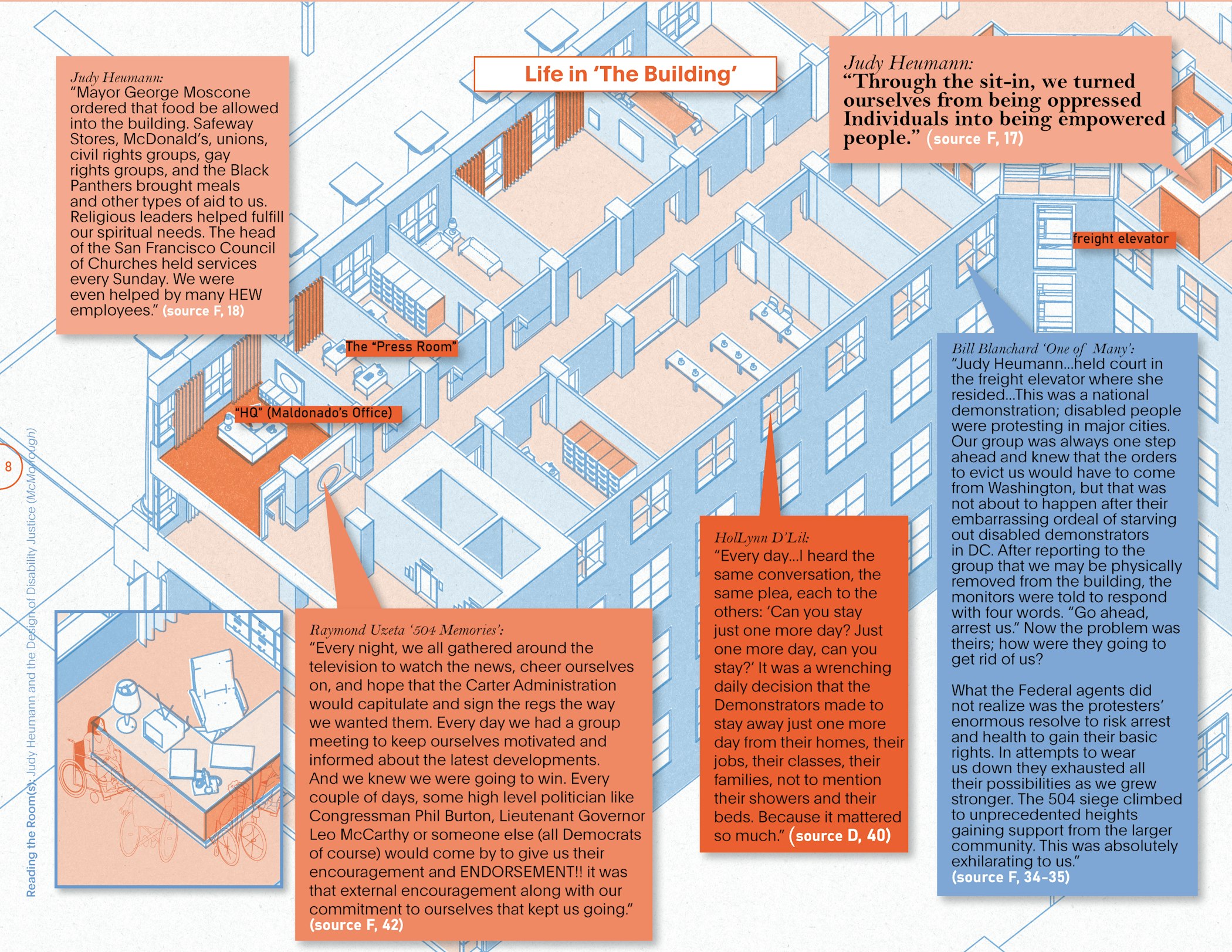

Having effectively scared Maldonado out of his own office, Heumann and Cone gathered the assembled protestors. Knowing that for a disabled person, there is nothing easy about an unplanned sleepover, and that many in the group were there without needed medications or personal attendants, Heumann remembered it as a ‘critical moment’ in which she felt unprepared for a large speech, and simply asked the protestors to stay until the regulations had been signed. “Please consider staying. We belong here.”[9] Seventy five people committed to staying, and despite the work ahead of them, Heumann recalled that “a sense of euphoria washed over the office. When you can’t live independently, you don’t get many chances to rebel.”[10]

Kitty Cone recalled that the ACCD threat of sit-ins was “brilliant, because rather than waiting until watered-down regulations were issued publicly and then responding, issue by issue, this meant the government would have to respond to the demonstrators. Additionally, it was not that easy to organize people, particularly people with physical disabilities, in those days, due to lack of transit, support services and so on. A sit-in meant people would go and stay, until the issue was resolved definitively.”[11] For three and a half weeks, the fourth floor of the federal building was more than a site of protest, it was a community that most of the disabled activists had never experienced, and where, by design, every member had a voice.

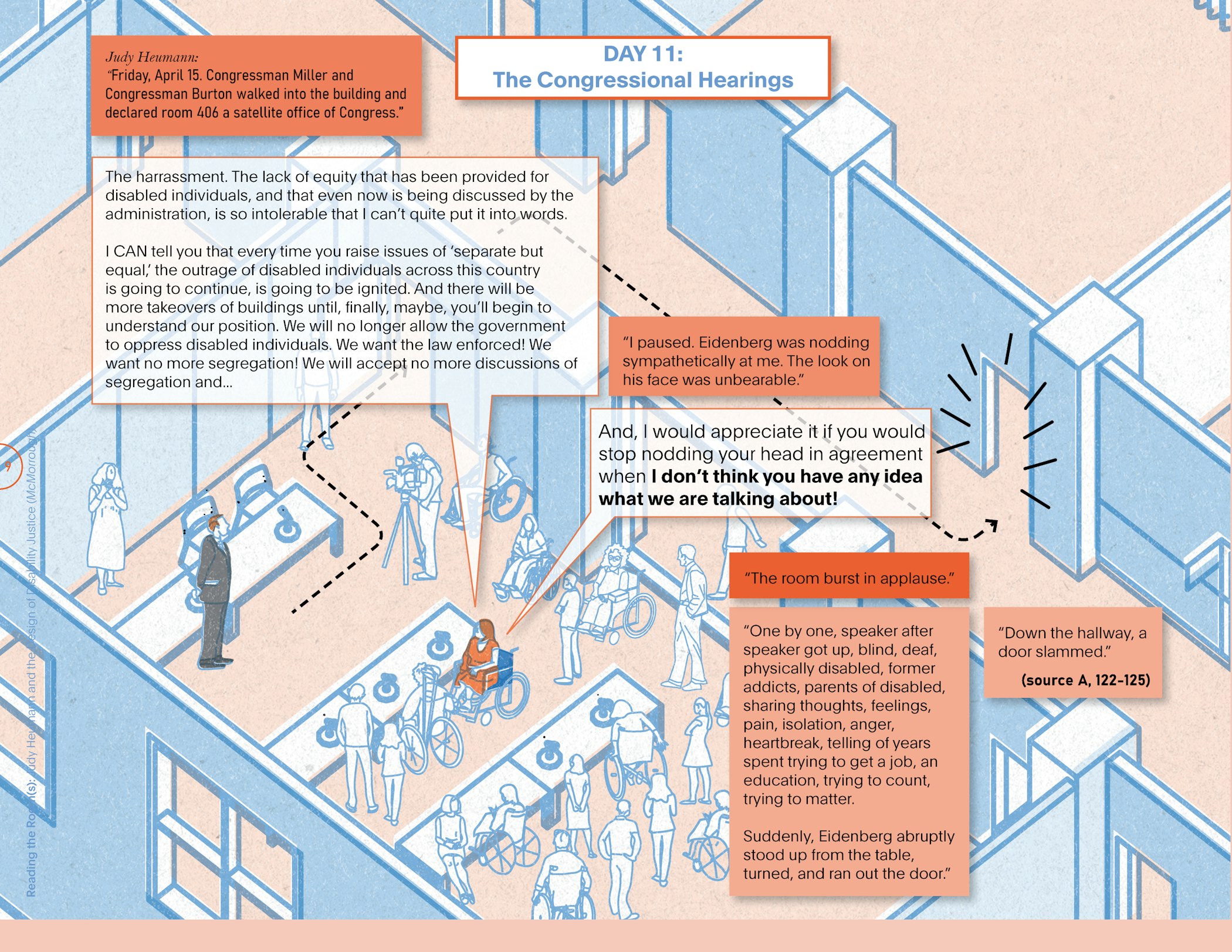

Mid-way through those weeks, April 15 stands out. In a Congressional hearing sponsored by California Congressmen Phillip Burton and George Miller, Judy Heumann addressed the HEW’s Eugene Eidenberg, sent by Washington to quell the protests.

These words - “I don’t think you have any idea” - are present in every barrier to accessible use, every empty gesture that misses the point, and every time accommodations within the built environment are presented as favors rather than civil rights. The 504 Sit-In exemplified design thinking that aimed its efforts at providing that missing understanding, and through a process empowered by thinking and re-thinking, imagining, evaluating and responding, all toward further imagining and a continual refreshing of effort, through the slow pace of embracing the mundane, it transcended it.

It’s not that Judy Heumann was simply in the rooms where things happened, it’s that she made them the places of action and result. Like a designer, she had a plan fueled by both hard-earned insight and unfettered optimism. She knew where she wanted to get, that even with preparation she’d have to figure it out along the way, and that “most things are possible when you assume problems can be solved.”[12]

Today, long after the introduction of 504, and almost 35 years after the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), we might think all has been taken care of, that the law has seen to it that barriers are no longer permitted, that we as architects always know what that means, and that no one need ever be impaired by the designed environment again. But accessible design is not reducible to a ramp or an elevator. While these might represent its physical and spatial manifestations, accessibility is dependent on the social, legal, and infrastructural frameworks that are often not visible to the untrained eye, just as the needs of the disabled in society can be easy to ignore by those responsible for making places and policies. The reality is that “a law cannot guarantee what a culture will not give,”[13] but every design can and should evaluate its responsibility toward how it shapes that culture. When examined from a different direction, something like a grab bar, a curb cut, or a zero threshold entrance is not ‘just an ADA rule,’ it is a hard-won right forged by Heumann and other disability warriors before and since. Designers should learn from this history, not only for its compelling humanity, but for its graceful ingenuity.