- Joy Knoblauch

-

I'll start the recording talking to Michelle Aebersold and Jonathan Rule, who have kindly agreed to talk with me today about their work. To start, could you tell me about how your collaboration began?

- Jonathan Rule

-

Do you want to go for that one, Michelle?

- Michelle Aebersold

-

Yes, absolutely. It started off as a meeting of faculty at the Center for Academic Innovation. This is where we met, we had faculty from all over and people had an interest in using virtual reality, augmented reality. Out of that sort of collaboration I met a lot of people across campus and eventually got more involved. I became an XR faculty innovator in residence and I received one of the early XR grants that Jeremy Nelson had put out and Jonathan had also received one.

Jonathan came on as a XR faculty innovator as well, and that's when I really started to get to know Jonathan and the work that he's doing and got excited about it, in part because, in my work as a healthcare professional, I've had an opportunity to be involved in different building projects in the hospital with regard to patient care spaces, and then also worked with the architects to design the Sim Center at the School of Nursing. I really like the whole design and building aspect of things, and we just kind of started talking.

- JR

-

Once we found each other and saw that there were common interests I think where we really started working together was because we both had projects in parallel through the Center for Academic Innovation. Michelle's were more geared towards medicine, mine were geared towards architecture. And then we said, “Okay, well, what if we put something together?” So how do you begin to have interdisciplinary teaching situations across campus and across disciplines?

They're still largely separate; Michelle's is mainly online and for nursing administrators or people that are interested in being nursing administrators, and mine is residential at the School of Architecture. But now, going into our third year of collaboration, we have the students collaborating virtually with each other throughout the course looking at how to rethink or redesign different spaces within Medicine.

- MA

-

Yeah, and I think it's kind of cool. It does bring to light some of the challenges that we all face in these kinds of interdisciplinary endeavors, trying to get students from different disciplines together. And then we layer on the added challenge of a residential course and a 100% online course. So meeting spaces and things like that tend to leverage some of the virtual options out there for us.

And we have people who've been involved in virtual options who are very interested in participating in some of this face-to-face. So I think we’ve created and opened some doors for our nursing students at that level who probably weren't exposed to VR in their undergraduate studies because many of them have been out of school for a bit.

- JK

-

Yeah, and I'd love to ask you to speculate about how architecture and nursing come together later on, but maybe first we should just say a little bit about what the project is, what are its aims?

- JR

-

So the current work that we're involved in is a grant through the VA hospital and Dr. Sanjay Saint. We call it the MWell grant.

- MA

-

Just to add, the parent grant that he has is through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality also AHRQ, so it's a really big government organization that focuses on many, many aspects of patient care, particularly around trying to improve the patient care experience and patient safety.

- JR

-

Dr Saint’s vision in this case is focusing on the ideas of what he calls “sacred moments” within medicine, which is the relationship between care provider and patient, or it could be also between two care providers or patient and patient, anywhere there's a moment of …

- MA

-

It took me a while to wrap my head around the thing, “Sacred moments,” but when you break it down, it's really that opportunity that you have to really be there with the patient. You know we're so busy in healthcare, running around, surgeons run in, 30 seconds later they and the team disappear. Patients often experience multiple providers coming in and out of their room. Sometimes nurses do this just because they're the person who's there all the time. But this is just even one step further, or one step deeper. It’s that sort of… that meditation experience where you can just sit and be there with your patient in the moment, whatever that might look like.

- JR

-

So this is actually from a white paper that they wrote exploring sacred moments in hospitalized patients: they describe “sacred moments” as “brief periods of time in which people experience spiritual qualities of transcendence, boundlessness, deep interconnectedness and spiritual emotions.” Others have labeled these moments as “‘sudden intimacies’ with total strangers that can occur at times of crisis or grief and that connect people in both unexpected and powerful ways.”

The project has a number of sub-studies, but we're specifically the nursing architecture sub-study. So it's funding to study how you might leverage Extended Realities as a way to test designs that would evoke moments like this within the healing process or within the communication process between patient and provider.

- MA

-

And this study is particularly timely for Sanjay because they have some opportunities coming up to redesign some of the healthcare spaces in the VA. So if they can work with us to examine some of these health care spaces in VR, as opposed to a physical mock-up, we can change it quickly. I think of it as an innovative opportunity to study something in a way that you may not always get funding to do.

- JK

-

I wonder, how are you having human participants engage with these spaces and answer a survey? Do they encounter other humans in this virtual space?

- MA

-

Yes, yes and yes. Jonathan, you want to go first?

- JR

-

Yeah, so we're setting this up and hopefully it's all ready in two weeks for our first trial run. But we've been developing what we're calling a base space, which is a typical spec hospital room from the VA hospital. We've gone through and looked at all their requirements, which are not necessarily code-based, but requirements by the VA if you were to design a new room, and so we're putting one of those together. We're also looking at what we consider an exemplary hospital room, and for this initial one, we'd like to do multiple, that way we can go and run through a couple different tests.

[Fig. 1] Interior view of virtual reality model of REHAB Basel by Herzog & De Meuron, 1994.

-

We have selected REHAB Basel by Herzog and de Meuron, and then we have also selected for this first trial run a sacred space, so it's a church or chapel that is in Lima, Peru. And so the idea is that we have two study groups:

One study group, which is going to be in person and in virtual reality, using room scale virtual reality, to test this out. They'll be at Taubman College with the Research Assistants that we have working for us. Then there’s the second study group, which is going to be all remotely online. They won't have access to the virtual reality headsets, but they'll be able to interact with this over their computer.

So we're setting up simulation scenarios that a nursing student is currently putting together. They're five to ten minute scenarios that the two nurses will have to either play out in virtual reality or on their desktop, and then afterwards they'll have a questionnaire to answer. The questionnaire has two parts: One is to understand the effectiveness of the extended reality experience based on desktop or virtual reality, which is called a “presence test," and so it's a fairly standard questionnaire that asks them about their experience within that virtual environment, and that will allow us to sort of gauge the fidelity of it as a resource for testing this. And then the second one uses a post-occupancy questionnaire for hospital spaces, it's a 20 part questionnaire, but we're only focusing on the one that deals with the patient or provider experience within it and especially the ability for the space to reduce anxiety or other other attributes of the actual built environment or, in this case, virtual environment.

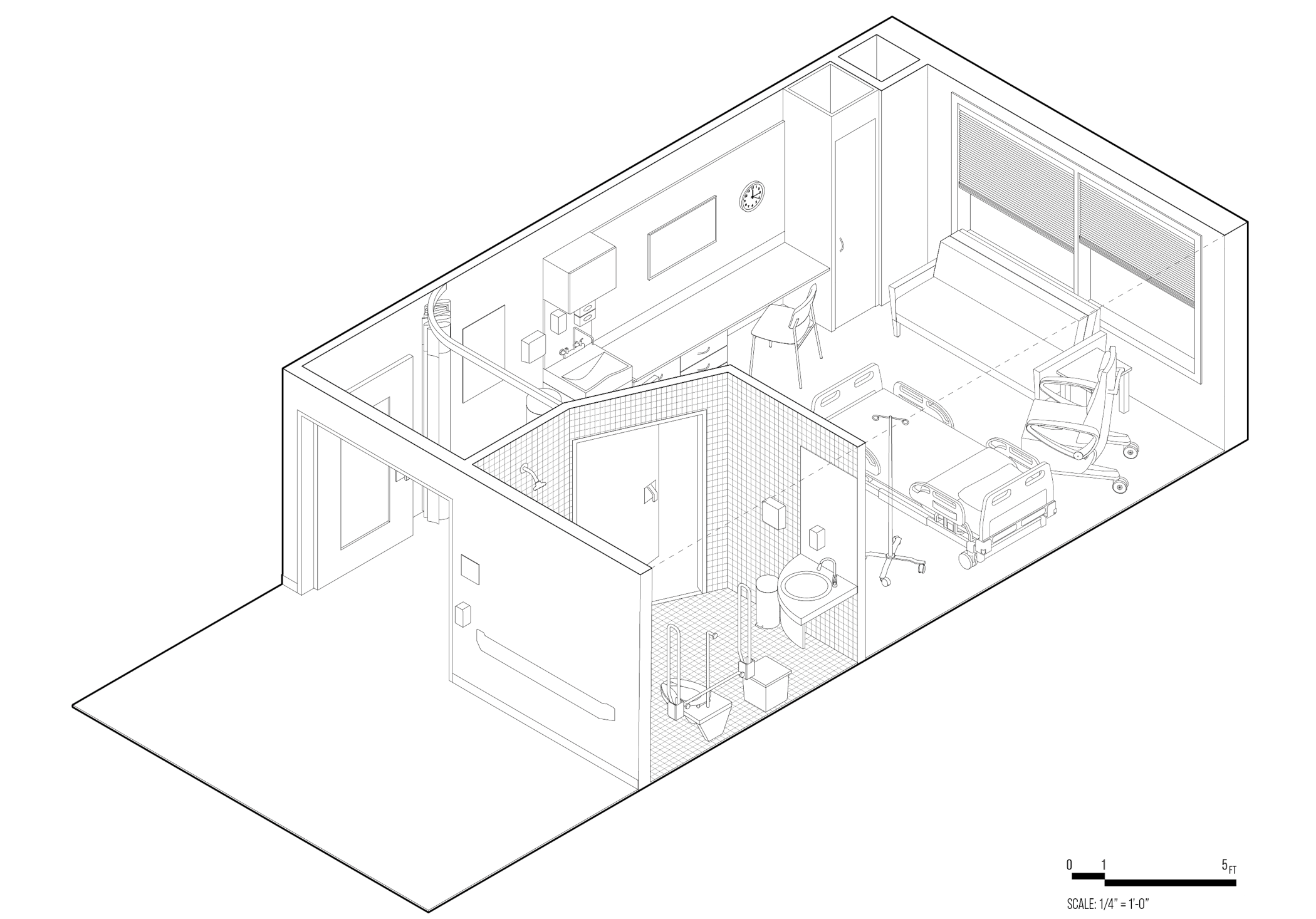

[Fig. 2] Axonometric drawing of a REHAB Basel room by Herzog & De Meuron, 1994.

We're hoping to understand a little bit how these scenarios might play out within the base hospital space at the VA hospital, the sacred space. I mean, it's a bit odd because it's not a hospital space this will be playing out in, but the idea is that there are architectures that are built for the sacred. We want to see if there is something we can learn from that or that might then contribute to how we might rethink hospital spaces or the atmospherics of it. And then we want to understand other exemplary hospital spaces:What can we learn from those? The next phase would be to actually design a new space for the VA or an initial space.

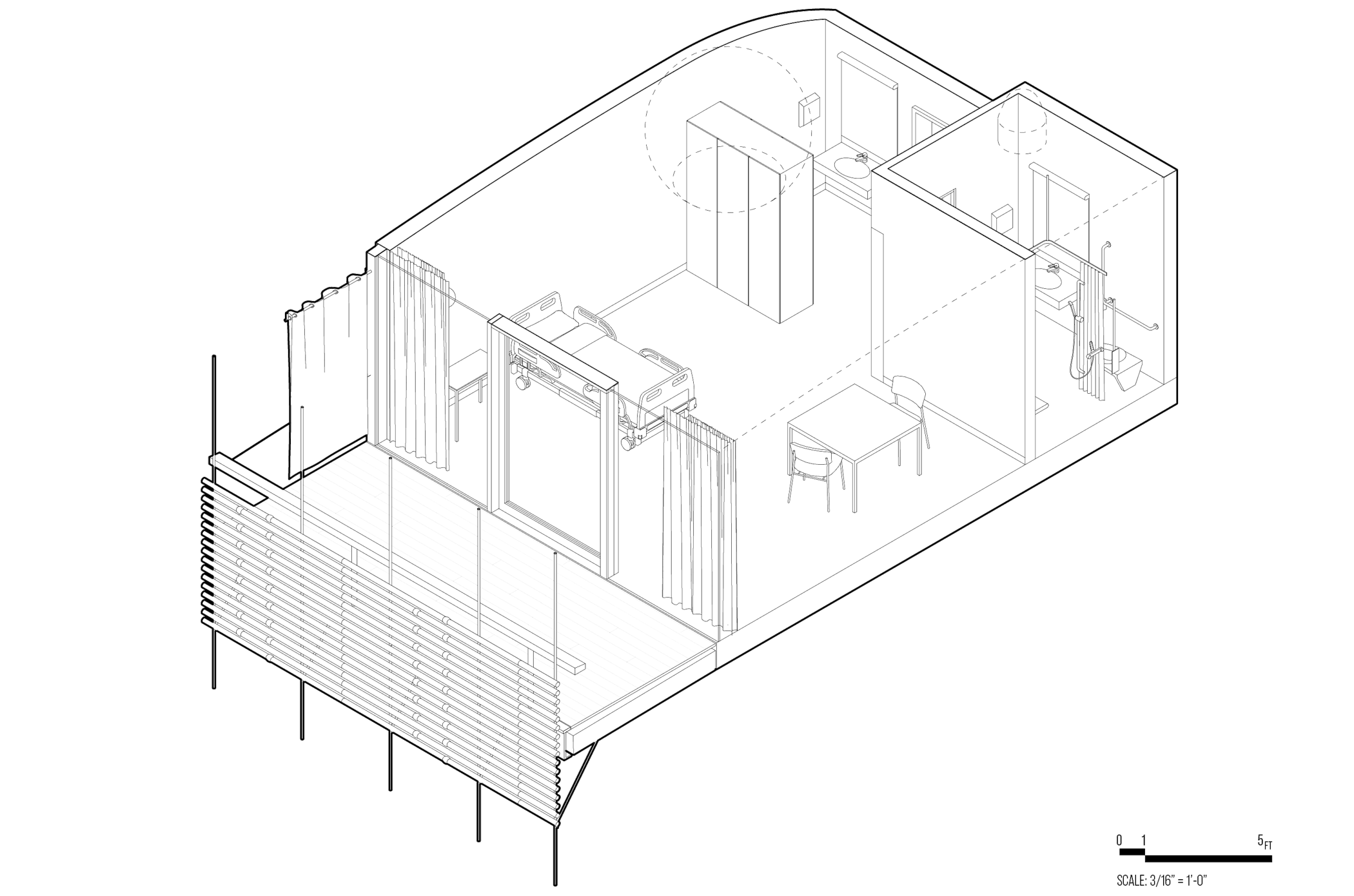

[Fig. 3] Axonometric drawing of a standard VA hospital room, 2024.

- JK

-

I can't wait to see the result.

- MA

-

Yeah, it will be interesting. It's just things that you don't always think about when you're building a space. Or by the time somebody higher up reaches out to the nurses and the nursing directors who are really on the front line delivering patient care, sometimes it's already too late. So I'm hoping that, by opening up this experience to others, some of our nurse leaders, when they hear, “Oh, we're going to be building new patient towers” or “We're going to be renovating patient spaces," they will raise their hand and say “We need to be at the table. We need to be a part of this, not bring us in at the 11th hour when most of the design work is done and we're not able to contribute."

So to me, that's just that'sa personal goal of mine: having our students recognize why it's important, why, of all the priorities and things you have to do, design is something that you want to be involved in. Ultimately, it's so that we can provide better care for our patients by doing it in spaces that are comfortable, safe, and conducive to many different aspects of care.

[Fig. 4] Interior view of virtual reality model of a standard VA hospital room, 2024.

- JR

-

What we've observed in the past two iterations of the course is not only an education in the nursing side of having them be better leaders or administrators, but, within that, educating them, so that if they are in a situation where they are, for example, developing a new hospital wing or tower they know what’s happening but also what the capabilities of the architect are and what they might be able to ask for.

I've noticed that it's not always “Oh, we need a whiteboard” or “We need this." Like, minimal things, that might not necessarily be a spatial implication. So how do you begin to educate those that might be at the table and making decisions? What are the things to look for that we can contribute from an architecture standpoint as well, and how do we engage hospital staff in the discussion in a more meaningful way and maybe get better results out of it?

- JK

-

Yeah, without the barrier, that representation. Often we as architects, we're often sharing these representations that are deeply meaningful to us but a lot of the appeal of an XR tool is that it's accessible to other kinds of brains who reason differently than architects do. These tools could help those groups have input way ahead of the process. I think that's a wonderful goal.

- MA

-

We started this program back when I was over at the health system and I think many places have done this too sort of like, “walk in your shoes." We would take people who were outside of healthcare but maybe in administrative positions or other types of positions, and have them just spend a day with a nurse or a day with a provider and just kind of see firsthand. So what's nice about this is that XR provides a little bit of that walk through as the nurses and the architects engage in walking through these spaces. We've even seen in the work that we've done so far, where there's just a lot of these kinds of learning points or “A-ha!” moments, or deepening of understanding, where the architecture students created something that they thought well, “This would be sort of a very nice feature," which it is, but then the nursing students say “This is great… However, we also have to make sure that it adheres to infection control standards, because we have a huge problem with hospital acquired infections” and things like that. So there's that really nice cross fertilization of understanding each other's work.

But you're right, the nurses always say, “Oh, we need a whiteboard," but okay, but maybe we can come up with something better, right? Like a whiteboard gets ugly after a while, after you've written on the board a million times. There's got to be something that looks better, that works better for everybody. Generally that doesn't happen.

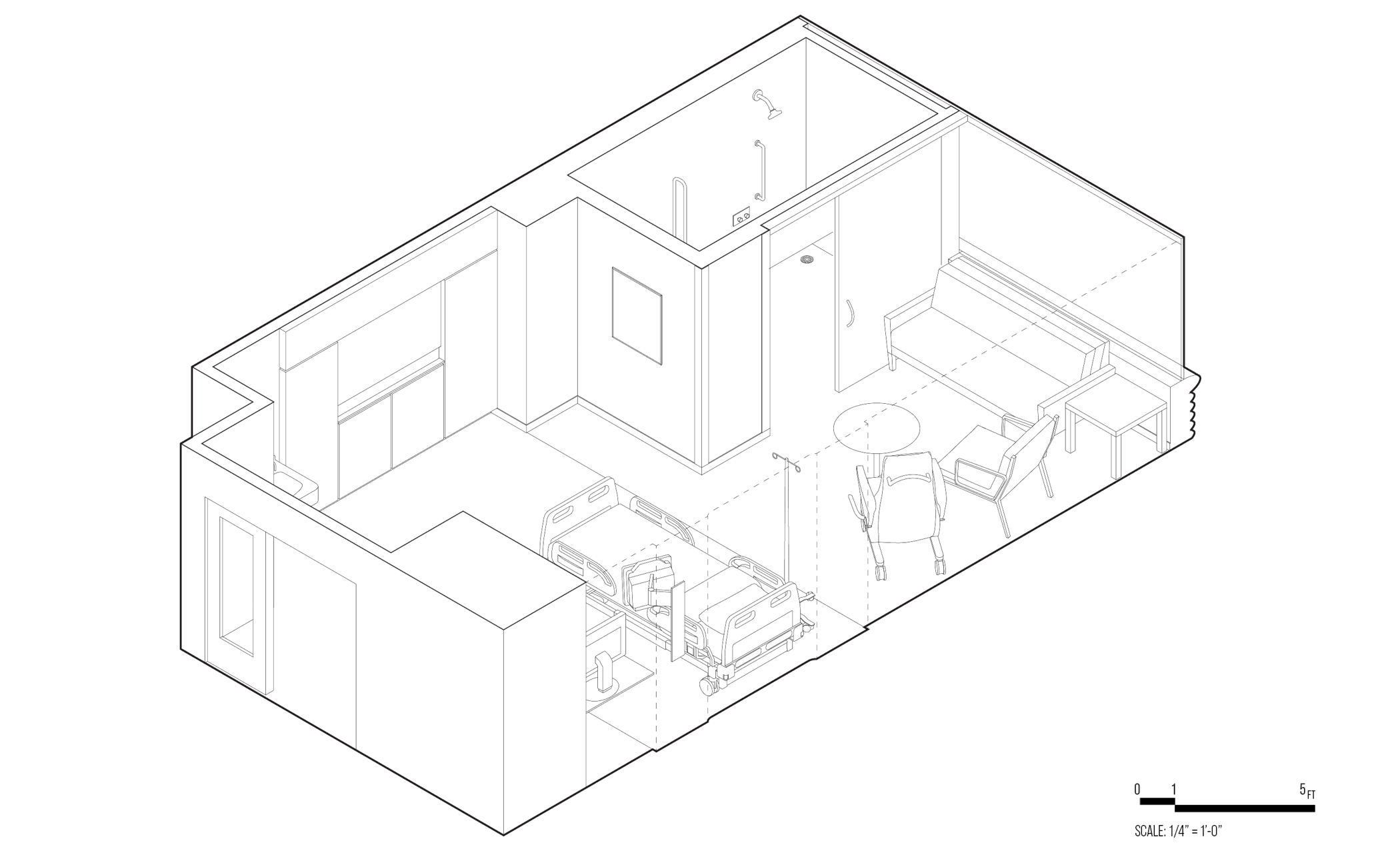

[Fig. 5] Axonometric drawing of a UPenn Hospital room by Foster & Partners, 2021.

- JK

-

Maybe that's a good place to zoom out and be even more speculative. As a hospital historian, I've long been interested in the connections between nursing and architecture. You know, journals from the 1910s, it often seemed like the nursing staff are the people who really understand what a building ought to have as far as how it should function and be cleaned and lived in and the lighting and all this kind of stuff, that the doctors seem to have a different awareness of architecture. But I wonder if you could speak to the ups and the downs, what's hard to translate and what's a good natural fit between architecture and nursing?

- MA

-

I'll start with where I have the biggest challenge. I don't know if my students would agree, but my biggest challenge is always trying to look at things from a very practical perspective, a very pragmatic perspective and from a patient safety and nursing workload perspective too, and think about room design from that lens. But, you know, looking at some of the art and the design and the things like that and using that to inspire and influence is probably not where I would have ever thought to go or even start. It's not that I don't love that stuff, I do. But just to think about it in a health care perspective is just different. It's like when we opened the Cardiovascular Center and you looked at that whole atrium, it's beautiful and it's so nice to be there. I would have never thought about that. I think that's been one of the biggest learnings for me. I mean I would have thought of things like, electrical plugs and HVAC and stuff like that, right? But not the aesthetics, beyond wanting something besides institutional beige paint.

- JR

-

Yeah, I think the charge of the project and the idea of the sacred moments needs to push back on that pragmatism a little bit. How do we open up the potential of design and thinking about medicine less as a utilitarian process? Through this idea of sacred moments, are there other methods of healing or showing how the environment can contribute to those methods of healing? And then we can try to shed light on that through examples such as sacred spaces or tea houses, where people come together. Thinking about those things, and how do you bring that in and use it as a resource? Or it happens in other places and they're positive and happy spaces to be in. Why can't we move that into medicine? Or why can't we test it at least in medicine and see what happens?

- JK

-

Well with the opportunities of virtual reality you can test so many things. It seems somewhat easier, and even slight modifications… That also seems appealing. “But what if it's a little bit more pink? Yeah, oh no, not pink… Okay, how about…?”

Well, this has been very valuable. I wonder if there are any last comments, things we haven't touched on, that you think readers who are interested in faculty research would want to know.

- MA

-

From my perspective, probably the biggest thing that I've learned over the past couple years is when you're trying something new and innovative like this, there will always be some of the students who are like, “You know, I don't see the relevance, I'm not sure why we did this”... But I think it's important to stay the course. Listen to the feedback and think about ways that, “Well, maybe I didn't explain it well enough," or “Maybe we didn't provide enough immersive experiences," or it might just be that that student wasn't as interested or involved, and that's okay. Because there have been so many other students that have really benefited and it's been a good experience.

The second time teaching the course I had a much better understanding and I could explain it better to the students than the first time around. Like the first time I felt I just kind of jumped off the end of the dock and into the lake and I'm like, “Okay, well, we'll figure it out," and that works for me. I'm very comfortable in that space, but you know a lot of the students are not. Like they need to know everything, and so when all your assignments aren't perfectly aligned or explained or I put something in Canvas that says “TBD, we'll figure it out." It creates a lot of unease. I think part of it is just helping some of the students work through that unease: this will be an experience and you're just gonna have to trust the process and it will work itself through. The second time around it was much, much better.

[Fig. 6] Interior view of virtual reality model of Meander Medical Center by atelierpro, 2013.

So it does take two and three iterations sometimes of these new and innovative ideas in order for you, as the faculty member, to feel comfortable. And I would say, as a student, embrace those possibilities. Not everybody gets an opportunity to do something fun, cool and oddly innovative.

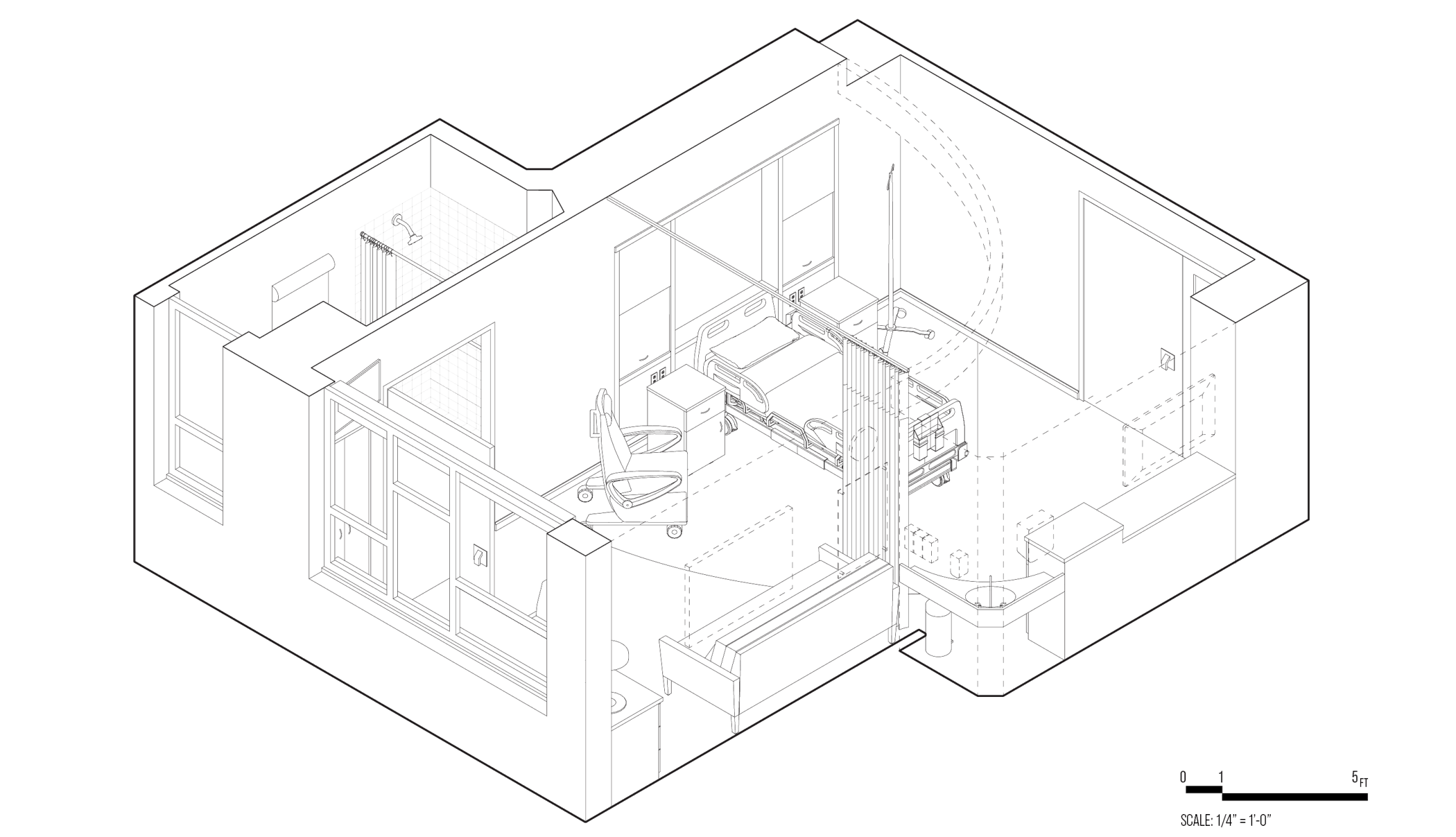

[Fig. 7] Axonometric drawing of a Dublin Methodist Hospital room by Karlsberger, 2007.

- JR

-

From my perspective, the lesson is to look outside the discipline. I feel like in architecture, sometimes we we look very much within the discipline and that is a standard, but then as soon as you start going outside of that and working with people that do not use our same vocabulary, there's a lot of things that you have to begin to figure out how to re-communicate, or communicate to get a positive outcome. And it's an important skill even for students to learn. Because, in the future, if you're going to be practicing as a professional a lot of it is about working with other people, not selling it to your faculty or your other colleagues.

So how do you negotiate things, how do you present things, how do you speak to things that you're designing that somebody else might have to understand and also then give you information back? It's always this back and forth. It's not just about presenting the projects to the nursing students, it's about working collaboratively back and forth in order to get a better outcome.

- JK

-

Those are words of wisdom from each of you and, I think, a great description of why I like working in design and health. It gets us as architects out of our heads but onto things that we do really care about and so I think that's been great. Thank you so much for talking about your work today.