Mining Architectural History with Neural Networks

2014 was a turning point in the application of techniques derived from AI research to the arts. This year saw the introduction of the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) by Ian Goodfellow[1] and the publication of the paper A Neural Algorithm of Artistic Style by Leon Gatys.[2] In recent years, these novel methods have taken hold in the arts[3] and music.[4] The newly emerging artform is fittingly named Neural Art.[5] The source of this term can be found in the title of a paper by Leon Gatys,[6] which forms the base for the work of several of the most prolific neural artists, such as Mario Klingemann (who describes himself as a Neurographer) and Sofia Crespo, whose series of works named Neural Zoo reflects a keen interest in the estrangement and defamiliarization of deep-sea creatures. There are many more artists in this area.[7] How is the oeuvre of these artists related to architecture? Maybe an example will help to clarify how provocative this novel method, is, in a good way, for architecture.

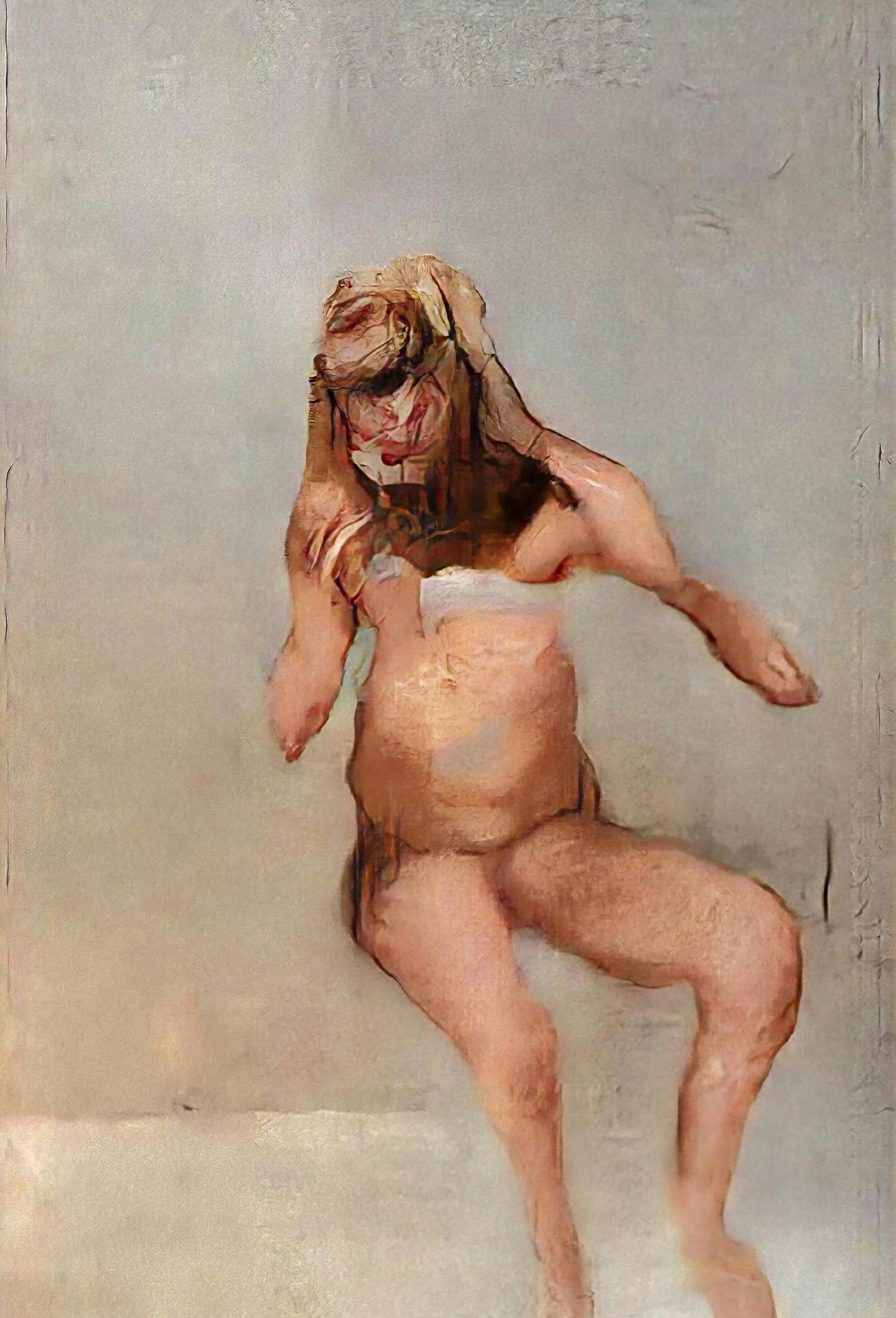

Mario Klingemann uses databases of Western art, mainly portraits, as the base for his StyleGAN[8] applications. Thousands of images from the Renaissance to the 19th century are fed through a StyleGAN algorithm. In a conventional case, StyleGAN would be used to create images that convincingly represent a known object to the observer. It might be necessary here to understand that Neural Networks are Function Approximation Algorithms.[9] They will always strive to achieve an approximation of, for example, the number 1. A curve can also describe function approximation. Thus the famous quote “Machine Learning is just glorified ‘Curve Fitting.'”[10] As much as this approach can produce convincing images of objects, the area outside the perfect fit of the curve really produces the more interesting results. They maintain a certain familiarity, despite their alien appearance. To come back to the work of Mario Klingemann as an example of what I mean by that: his images and animations maintain elements of the dataset informing the StyleGAN. This results in images showing contorted bodies and distorted faces that have a surreal quality: bizarre Janus heads with multiple faces, strange Cyclops, monstrous Chimeras between humans and animals [Fig. 1]. The trained eye will still recognize features of historical paintings and drawings. A bit of Goya here, some Whistler there, glimpses of Jeanne-Etienne Liotard, Eduard Magnus, Lenbach, and Winterhalter. But none of the images is designed to approximate the particular artists, as “This Person does not Exist” would do. Rather it renders the features that were recognized by the neural network and re-combines the pixels into a new image outside the conventions of how we as humans understand the depicted object. In doing so, the emergent pieces of art provoke questions of authorship and agency. In addition, the question of the value of a sensibility that was created somewhere between human input and machinic output is raised. Is this the art of the posthuman age?

[Fig. 1] Mario Klingemann, The Butcher’s Son, 2017. © Image: Quasimondo

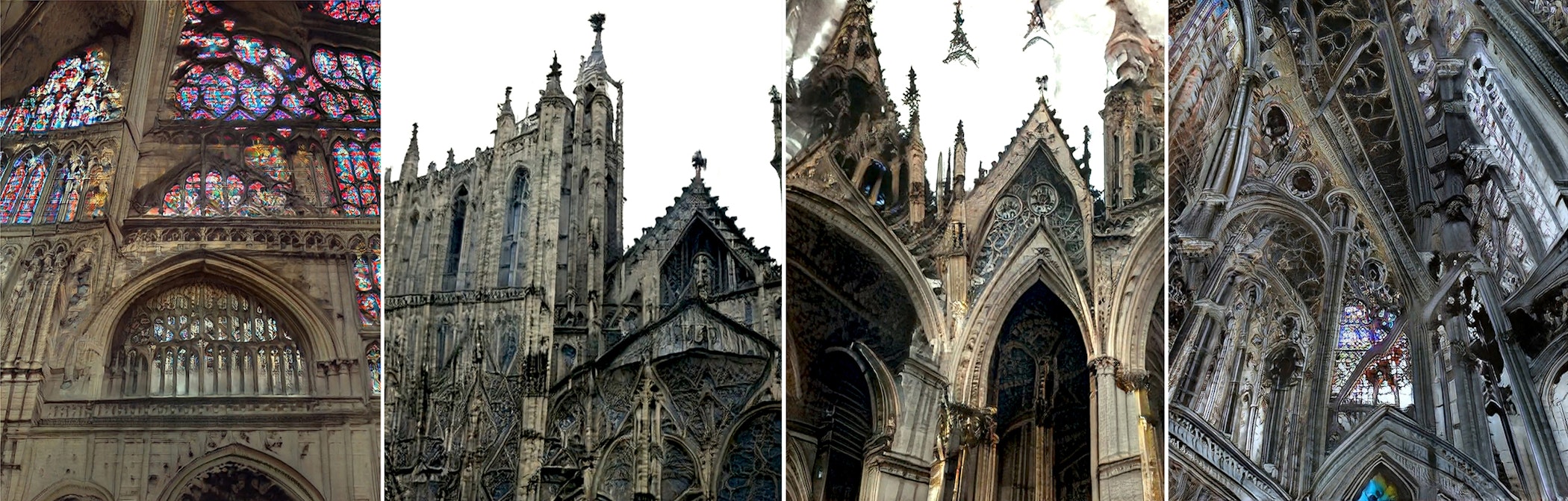

To illustrate an example in the field of architecture, we collected Gothic architecture images. We used them as a dataset for a StyleGAN [Fig. 2]. Ironically using the ever-so-popular "scraping" method to collect “Goth” images results in, let's say, “interesting” results. Does this development consider the possibility of evaluating the role of humans in a world where the boundaries between human and nonhuman creativity are blurred? In architecture, we can observe a similar tendency with architects increasingly picking up on novel techniques in machine learning and machine vision. I would describe this new tendency in architecture as Neural Architecture, borrowing from computer science and neuroscience as much as from the language used in the arts and music (neural art, neural music).

[Fig. 2] StyleGAN based on a gothic architecture dataset. © Image: SPAN 2020

Familiar but Strange: BITS, PIECES, FEATURES AND NEURONS

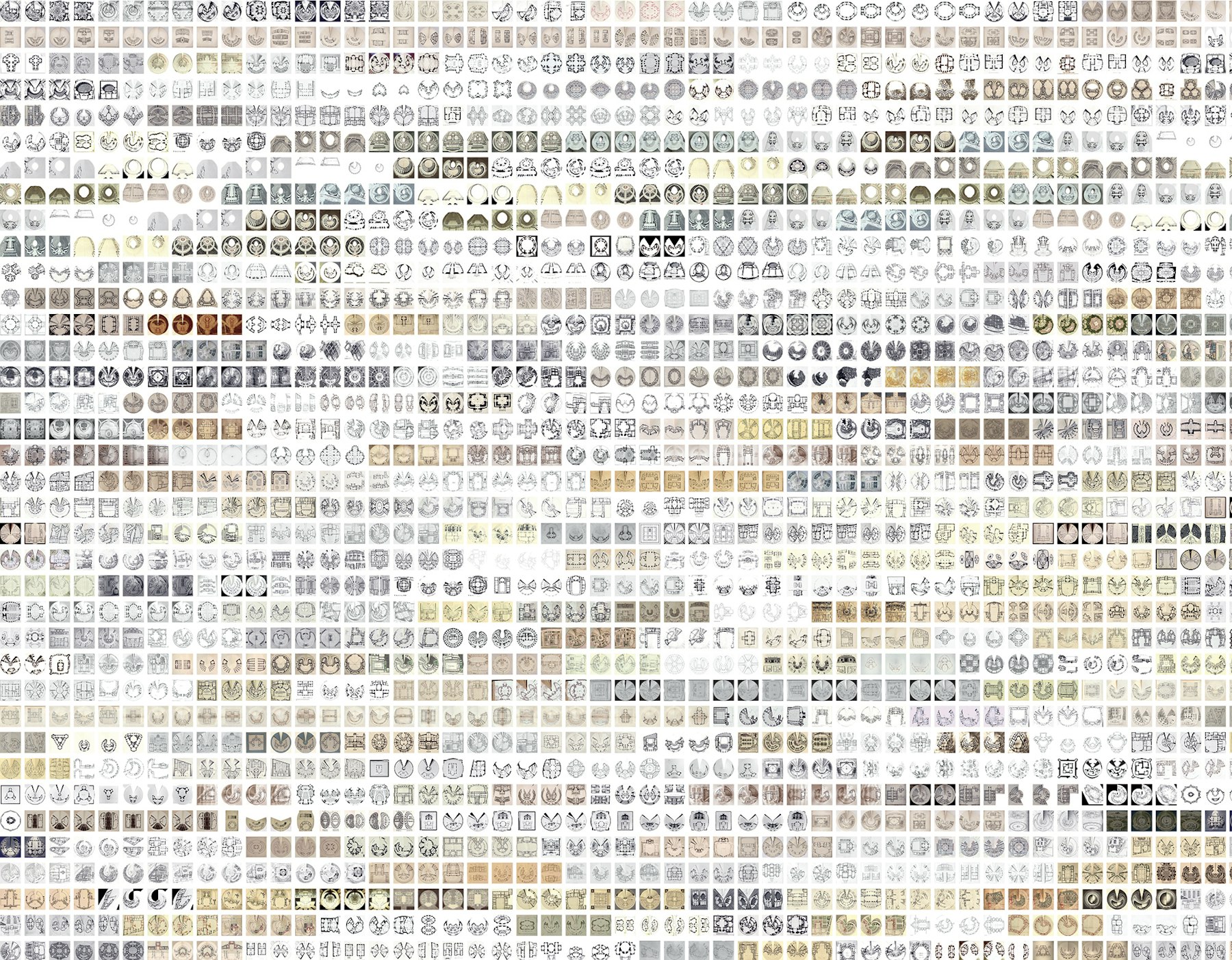

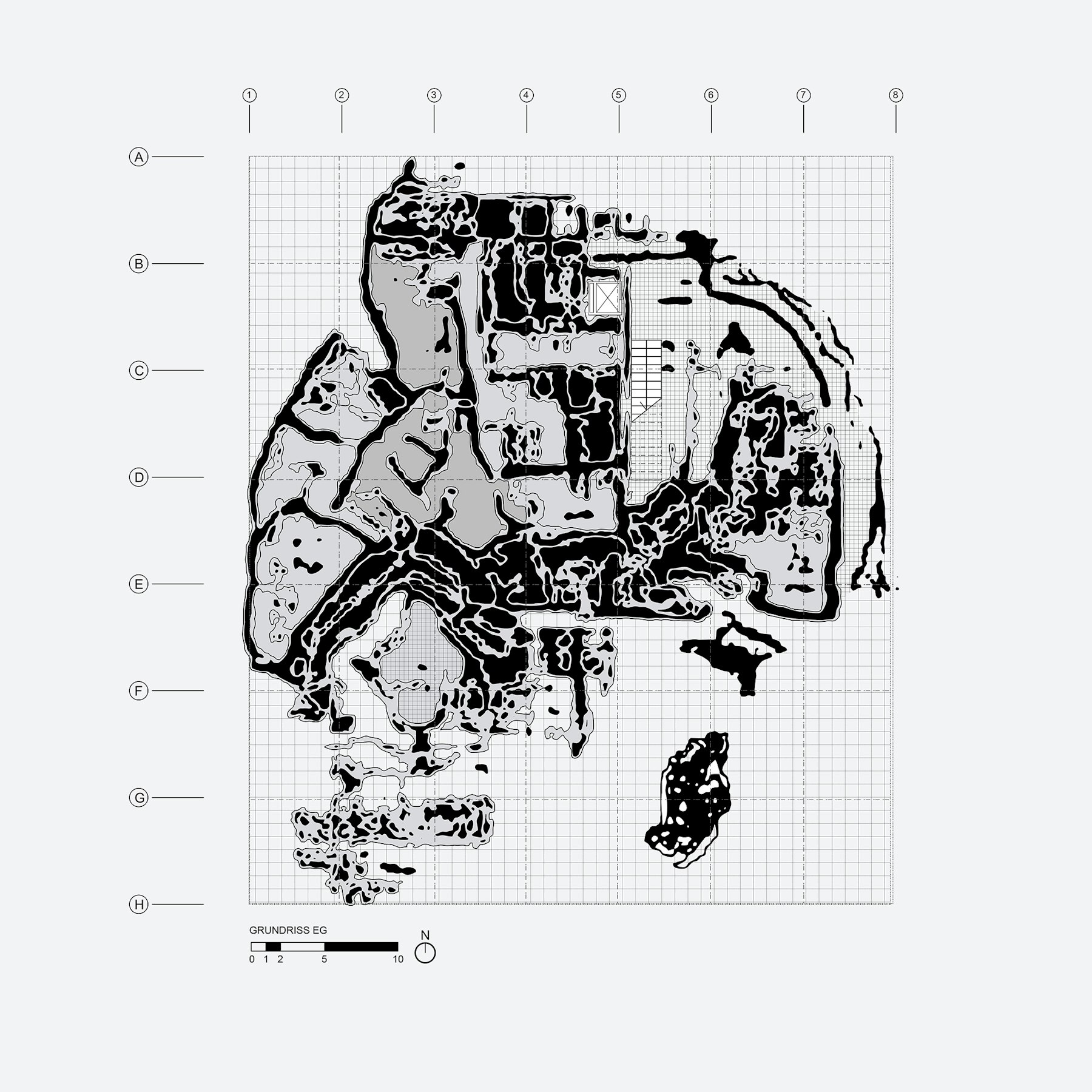

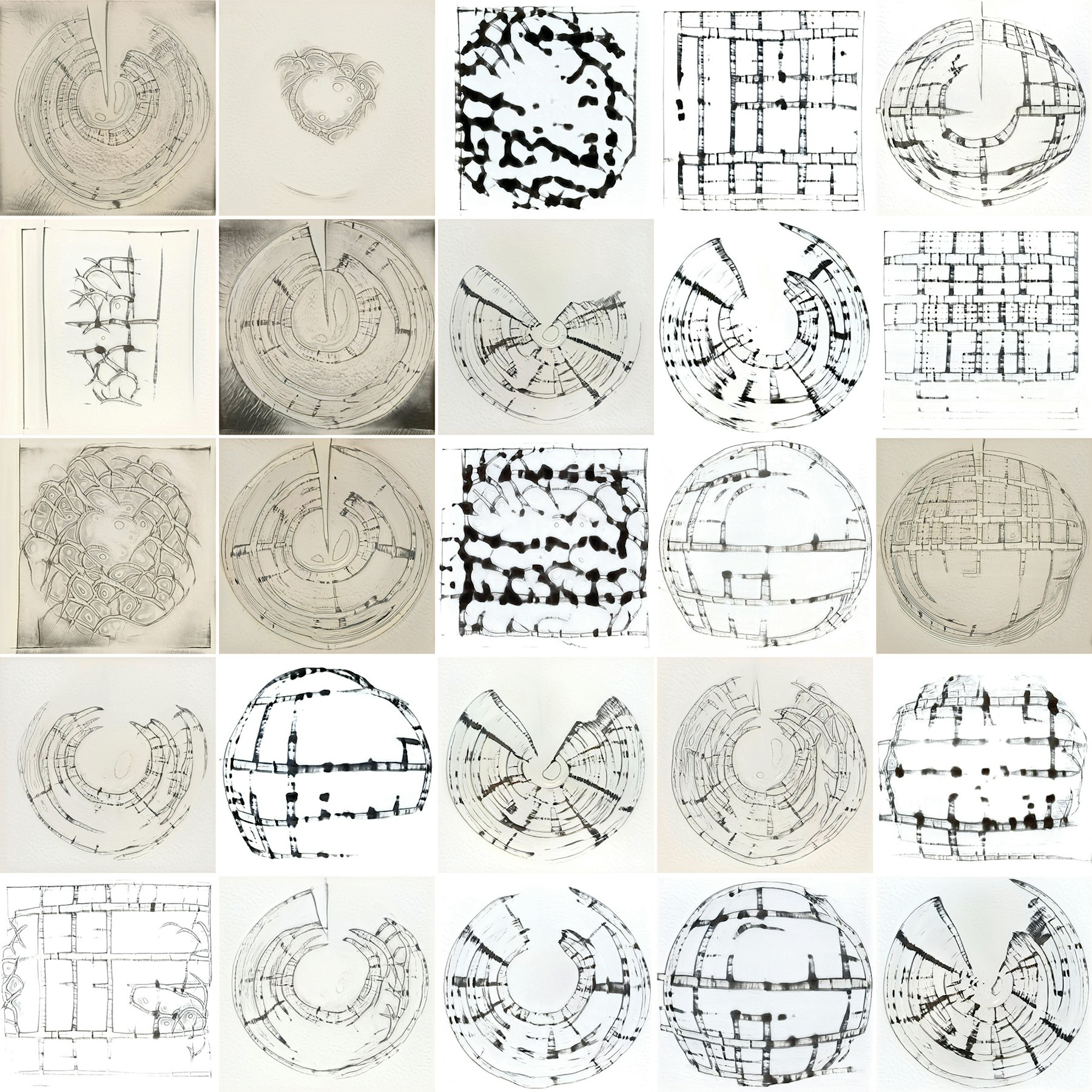

I have relied on neural networks to train datasets in my work, exploring them in a reverse flow of information, which means that algorithms usually trained to recognize objects, such as in automated cars, are used to perform generatively instead of analytically. This is a similar technique to the ones used by the artists mentioned above (Sofia Crespo uses a very similar 2D to 3D Style transfer technique to the one I have been using in recent years)[11]. To give you a more concrete example, let me rely on an image-based approach: using a database with several thousand Baroque plans [Fig. 3], we experimented with how a neural style transfer would imprint the learned features from the Baroque plans to a Modern plan. Echoing the conversation about the work of neural artists, we achieve results that are familiar but strange at the same time. The nature of Baroque architecture reflected in the dynamic opposition and intersection of elliptical volumes of space, the thick pochés, undulating walls, and rich surface treatment are features that are learned by the neural network and applied to Modern plans [Fig. 5]. Even though this is a simple experiment, it was a proof of concept that this method does not simply imitate a style or create a crude collage of elements. Still, it produces unexpected, highly provocative, and yes—inspiring—images.

With this novel toolset come a whole set of questions concerning their ontological and epistemological qualities. How do they change the way that architects conceive of their projects?

[Fig. 3] SPAN, Baroque Dataset, 2020. Images of 1562 Baroque Plans © Image: Matias del Campo, 2020

The Dependency Between Concrete and Abstract Objects

Neural Networks Are Abstract Objects

[Fig. 4] Matias del Campo & Sandra Manninger, Neuroplan 1, 2020 © Image: Matias del Campo & Sandra Manninger

[Fig. 5] An example for plans resulting from a GAN learning features of Modern and Baroque plans after 3000 cycles of training. © Image: Matias del Campo & Sandra Manninger

What does that mean? To unpack this problem, we need to divide the problem into its specific components. The assemblage of elements needs to be laid out. Knolling the problem. In neatly laying out the particular parts of the conversation, we hope to achieve a clear overview of the challenge architecture is currently facing in the gestalt of a novel agent in design. Unpacking the pieces, unwrapping them, and cleanly positioning them on a flat surface allows for a clear overview. First of all, we need to discuss the ontological qualities of this problem. We are talking about architecture. To define architecture in itself borders on the naïve, as it contains manifold problems reaching from purely practical to cultural, aesthetical, and ephemeral aspects. Instead, we will unpack the problem by closely looking into the meaning of neural networks and slowly and methodically working ourselves towards the aspects of the epistemology of the object we are observing and the aspects of paradigm and theory that they produce.

As described above, neural networks are prolific in recognizing relationships within a set of data. This is one of the reasons why this method is such a provocation for architecture. The traditional role of the architect is not very different. Architects are trained to recognize, understand and process a large set of correlated information to assemble them in a project. Just think of an architecture competition situation. There is a call for a competition. A group of rules in the form of programmatic, technical, social, and economic aspects is established. The specific program calls for the architect’s knowledge, experience, and expertise to synthesize the rules in the form of a design idea. How does this knowledge emerge? Let’s be concrete about the problem by assuming it is a specific competition. Maybe a theater? A very concrete object.[12] To achieve this concrete object, a set of abstract objects must be established first, such as plans and sections that are based on calculations, numbers, and diagrams demonstrating the spatial relationships. This produces a set of ontological dependencies, not only between concrete (material in the form of a building) and abstract (design, plans, sections) objects [Fig. 4 & 5] but also between the concrete object and the set of data present in the architect’s mind. How many theaters did s/he design before, how many did s/he see, how many images of theaters were absorbed? Admittedly, this is a weak ontological dependency, but a dependency regardless. With this in mind, we can interrogate these entities—these examples of theaters in the architect’s mind—by their properties.

Properties

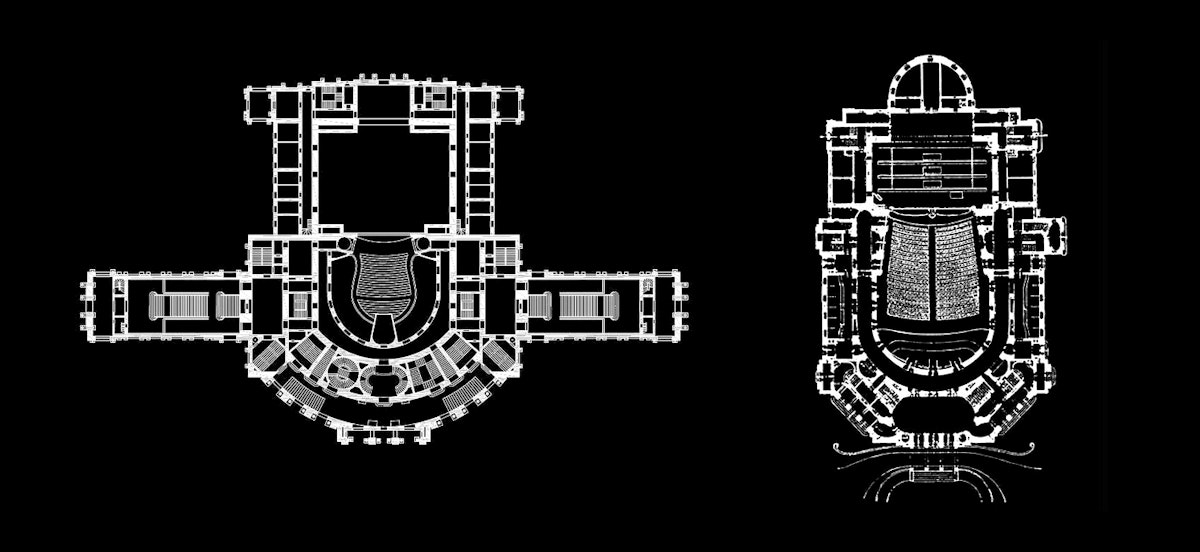

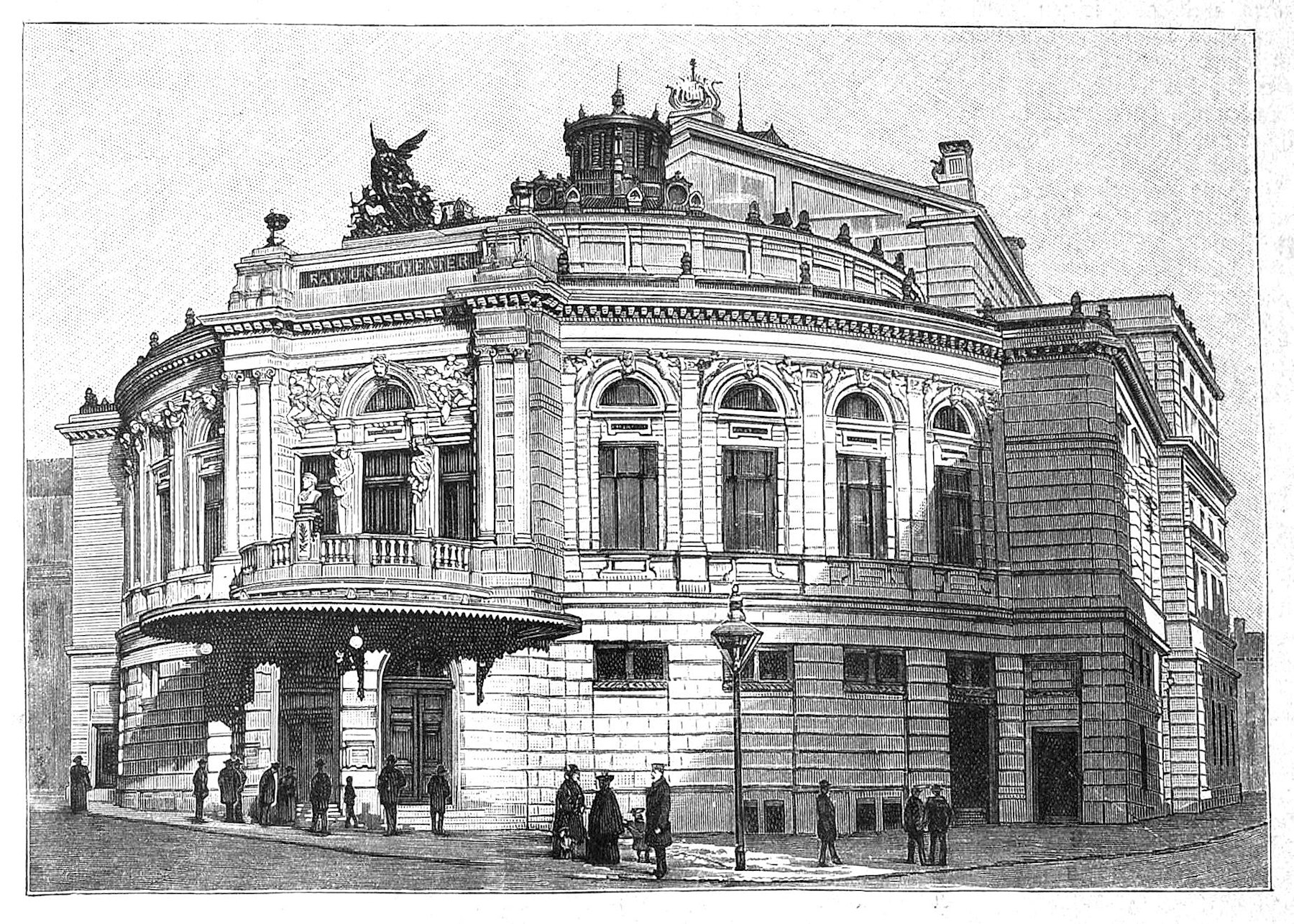

What is meant by properties? Properties allow the comparison of entities with one another. To stay with the theater example: the Burgtheater[13] in Vienna has an audience chamber and a stage tower. So does the Theater an der Wien, the Raimundtheater[14], and the Volkstheater[15] (I am just sticking to theaters in Vienna, as I know them best [Fig. 6]. So we can assume that the audience chamber and the stage tower are properties of a theater[16] in that they are universally present in theaters. Any number of theaters can share them. To that extent, we can consider the theater as an object with a bundle of properties (it would be easy to name more general properties of theaters such as ticket boxes, lounges, rehearsal rooms, wardrobes, green room, administration, buffet, coat room, etc.) This might be true for every architecture that operates with a specific program which ultimately represents a compresence-relation responsible for the bundling. Of course, it is necessary to distinguish between the categorical and dispositional properties of an architectural object. When talking about categorical concerns, we discuss what something is like, meaning which kind of qualities it has. Dispositional qualities discuss the potentialities of an object (which, for what it is worth, can be tied to Manuel DeLandas conversation on potentialities).[17] The Burgtheater has a definite shape, a categorical property, while its tendency to provoke thunderous applause (or at times booing) is a dispositional property. Concerning the discussion on AI and architecture, we are primarily interested in the categorical properties as these can be examined by neural networks, such as shape, dimension, plan, section, umriss, pixels, etc. For this reason, we would also include color in the area of the categorical properties as neural networks divide color into their RGB values, into numbers that can be interrogated for their properties, thus positioning themselves within the conversation of abstract objects.

[Fig. 6] Plans Burgtheater, Volkstheater © Image: VBW, Vereinigte Bühnen Wien

Relations

When talking about the properties of a piece of architecture, it seems evident to also discuss the relationships of these objects to each other. Traditionally in architecture, the discussion of the relationships of buildings to their environment, whether urban or rural, is described as the contextualization of a building. I do not know how many hours I spent in Hans Hollein’s office discussing the contextualization of a particular building. How does this axis meet that axis? How does the sun rotate around the building? What are the proportions and scales of the buildings around the project? I had to build dozens of models, physical models in blue foam, with variations of how a building is contextualized in its surroundings [Fig. 7]. Later I applied the same method in a digital context, allowing me to increase the possible variations into the hundreds. Today, it is datasets with thousands of examples [Fig. 8]. This short story demonstrates the transition from the age of data scarcity to the era of data abundance, and the struggle to harness the inherent information. Or as Mario Carpo put it:[18]

The collection, transmission, and processing of data have been laborious and expensive operations since the beginning of civilization. Writing, print, and other media technologies have made information more easily available, more reliable, and cheaper over time. Yet, until a few years ago, the culture and economics of data were strangled by a permanent, timeless, and apparently inevitable scarcity of supply: we always needed more data than we had. Today, for the first time, we seem to have more data than we need. So much so, that often we do not know what to do with them, and we struggle to come to terms with our unprecedented, unexpected, and almost miraculous data opulence.

Circling back to the statement about architects operating as data miners, the response to Carpo’s concern about how to harness the qualitative information of big data to inform the architectural project at hand is the use of neural networks. Neural networks process enormous amounts of data, but they also need massive amounts of data to learn anything of value, whether relationships (contextualization), features (properties) or behavioral patterns. To this extent, the collision of the wealth of data produced by the architecture discipline throughout its history with processing methods borrowed from artificial intelligence results in the field of Neural Architecture.

[Fig. 7] Matias del Campo, Sandra Manninger, Alexandra Carlson, Dataset of 1654 3D Models for a GraphCNN Database, 2020 © Image: Alexandra Carlson

About Features of Things and How to Capture Them

What does this mean for the relations between these architectural objects? We can find a close connection here to the aspects of properties, in that both—relationships and properties—describe the character of the things they are applied to. Occasionally properties are described as a special case of relations.[19] The example of the theater as the architectural object described in this essay allows us to differentiate between internal and external relationships. The Burgtheater and the Raimundtheater are in an internal relationship of similarity to each other as both are theaters [Fig. 8].

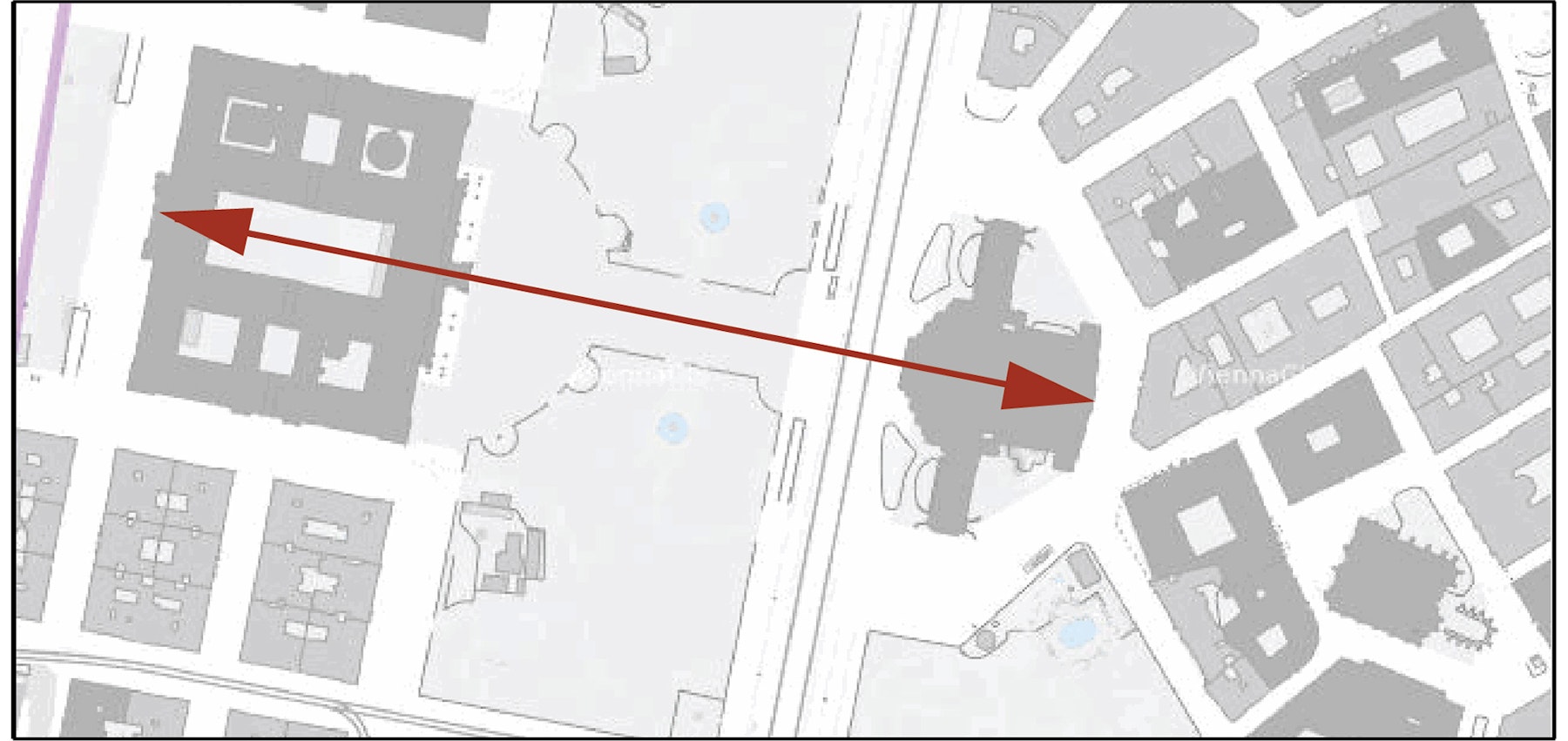

The relata of similar features determine the relationship. As evident and almost simplistic as this insight seems to be, it is crucial for the operation and inner workings of neural networks. Features and the relationships to each other (for example, in an image) make it possible to train a neural network to recognize a theater—or anything else it is trained to recognize, for that matter. Currently, this method is utilized in machine vision tasks that allow, for example, self-driving cars to recognize other vehicles, the street, signage, people, dogs, and cats, by understanding a family of internal relationships within a large number of images. In architecture, we can use this ability in an analytical way and in a creative sense. The flow of information can be reversed to generate a theater instead of recognizing one. I would like to emphasize the impact of such a motion, as it opens up questions about agency, authorship, aesthetics, and sensibility. Apart from the consideration of internal relationships, there are also the aspects of external relationships. As briefly discussed before in architecture, this discussion would gravitate around the contextualization of a building. In contrast to internal relationships, external relationships in architecture are not defined by similarities. The Burgtheater is at the Ringstrasse; it stands in an axial relationship to the Rathaus (Figure 9) but has no similarities to it. The architects of historicism, such as Gottfried Semper (Burgtheater) and Friedrich von Schmidt (Rathaus), specifically used very different features to evoke the meaning of the content of the building. While the Burgtheater was designed in a Neo-Renaissance style (because, Culture, you know...), the Rathaus (City Hall) was designed in a Neo-Gothic style, evoking the origin of citizen representation in medieval Flemish towns (what this has to do with Vienna is up to a Friedrich von Schmidt scholar to explain).

[Fig. 8] Burgtheater and Raimundtheater © Image: VBW – Vereinigte Bühnen Wien

[Fig. 9] Relationship of Burgtheater and Rathaus, Vienna, Austria © Image: Matias del Campo

Things, Facts and the Ontology of Neural Networks

After defining that neural networks are abstract objects defined by their properties and their relationships, and dabbling in abbreviated definitions of some of the terms used in this article, one more question remains: Is Neural Architecture a thing or a fact? Why is this relevant within the conversation laid out in this essay? It is very alluring to declare that every architecture is a thing, and thus every aspect and part of it is a thing too. But is this so? What about plans, calculations, proportions, simulations? Are those things or facts? Maybe it would help to first briefly define what is meant by things and facts in this conversation. Thing ontologies discuss the possibility that the universe is made of a plurality of discrete objects.[20] To this extent, the paradigmatic example of a thing ontology would be atomism,[21] in contrast to non-thing ontologies, which consider that an object is not necessarily an assembly of objects but could also be one continuous object. For our conversation, let us stick to the idea of neural networks being things in that they represent an assembly of objects. These discrete objects can be the databases of individual images or individual .obj[22] models (as in the research on GraphCNN design methods)[23] or the numerical data of images (in the form of their RGB values) or the layers in the networks that fulfill different tasks such as edge recognition (Figure 10). How are these things and not facts? Or are they both? Let’s take a materialist point of view (and materialist is interchangeable with realist in this conversation). We can assume that the calculation of neural networks is based on material processes: electrically charged matter.

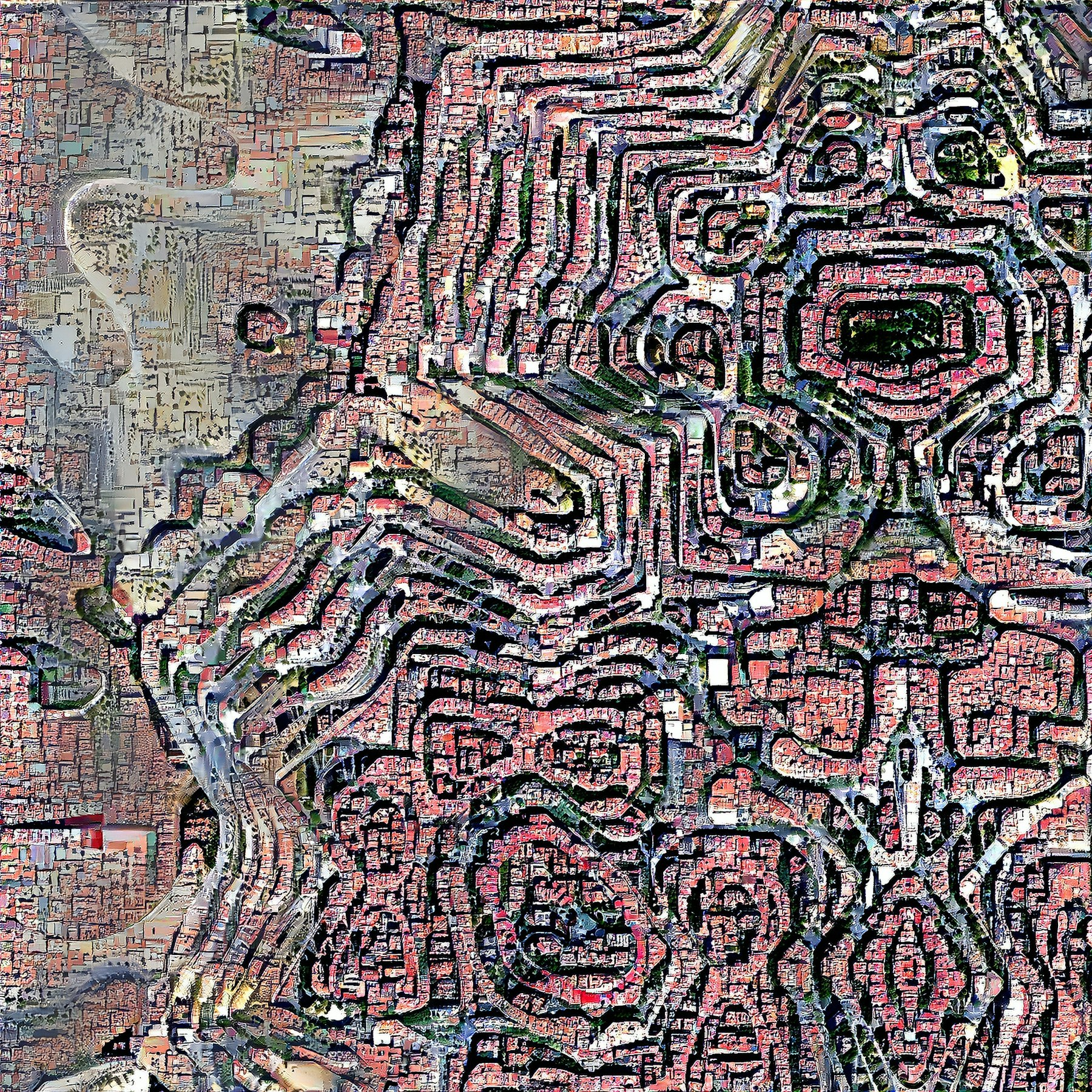

[Fig. 10] SPAN, Matias del Campo, Sandra Manninger, Urban Fiction – Vienna, 2020. The neural style transfer breaks the content and style image into the individual pixels’ RGB values to perform the process in a convolutional manner. Several layers detect aspects such as edges, blobs, and corners, to process them through the network further © Image: Matias del Campo

[Fig. 12] SPAN, Detroit, 2019 © Image: SPAN, Matias del Campo & Sandra Manninger

A sequence of moves creates a set of physical phenomena resulting in an electric current used to run computers and their respective GPUs, made of Silicon, Tantalum, and Palladium, that calculate the numbers laid out by a set of algorithms known as neural networks. All of which are things operating in discrete processes to create a result. The result can be the successful recognition of a car, a person, a dog, a sign or a voice—or the creation of an image that we describe as art (Sofia Crespo [Fig. 11], Mario Klingemann), music (Dadabots, YACHT, Holly Herndon) or architecture (SPAN [Fig. 12], Daniel Bolojan, Immanuel Koh, etc.). What if neural networks are not things, but facts? What is the difference? Things are, in general, put in contrast with the properties and relations they instantiate,[24] In contrast, facts are described as adhering to the items in combination with their properties and relations as their constituents. In short, facts swallow things and their properties/relations versus things in themselves, maintaining independence in a flat ontology.

[Fig. 11]Sofia Crespo, Neural Zoo, 2019.

What About Aesthetics, Agency, and Authorship?

There are three takeaways here for the conversation on neural networks and their meaning for the architectural discourse. Neural networks are things; they are abstract objects with properties. They maintain internal and external relationships within a flat ontology, and they constitute discrete assemblies.[25] After interrogating the ontological frame in Neural Architecture, it might be time to ask if we gathered any knowledge from the structure we laid out. Do we know more now that we have explored questions such as objects, properties, and relations between elements at play in Neural Architecture? Most importantly, the previous interrogation already hinted towards some of the epistemological questions that arise from neural networks work, such as the aesthetics, agency, and authorship of the resulting project. Relevant for the frame of conversation in this essay are the positions of Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault about the nature of authorship and author-at-large. These critics interrogated the role and relevance of authorship pertaining to the interpretation or meaning of text. This can be expanded to all areas of artistic production, as, for example, to architecture in the present text of this essay. Barthes, for instance, attributed meaning to the language and not the author of the text. Instead of relying on the legal authority to exude authorship,[26] Barthes assigns authority to the words and language itself. Foucault’s critical position vs. the author can be found in the argument he presents in his essay “What is an Author?”[27] Foucault argues that all authors are writers, but not all writing is literature—echoing a broadly discussed sentiment in architecture: not every building is architecture, and not every architecture is a building.

Aesthetics of Neural Architecture

The term “aesthetics” is a highly charged one in architectural discourse. This includes considerations such as the antithetical position of Peter Eisenman, who demanded that figures of architecture should be read rhetorically instead of aesthetically or metaphorically,[28] or Anthony Vidler's discussion of aesthetics along the lines of its functional and metaphysical properties such as the sublime.[29] I would propose first to interrogate the etymology of the word “aesthetics” to unlock its meaning for the frame of discussion in this article. Greek in its origin (aisthēsis), the term aesthetics means perception by the senses (which brings us right back into the discussion of feature recognition). The German philosopher and father of our modern understanding of the term aesthetics as the science of sensory knowledge directed toward beauty—Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten - considered art to be the perfection of sensory awareness.[30] It is vital to understand that the term aesthetics has undergone a series of mutations since Baumgarten’s time, and that even contemporaries of Baumgarten, such as Immanuel Kant, had a very critical position towards Baumgarten’s definition. It lacked—according to Kant—any objective rules, laws or any principles for that matter, able to describe natural or artistic beauty.[31] In contrast to the objective usage of the term aesthetics, Kant relied on its use in a subjective manner as it relates to the internal feeling of pleasure—or displeasure—and not to any qualities in an external object. The assertion of Baumgarten that the three guiding principles of aesthetics are “Good, Truth and Beauty” appear essentially naive in the contemporary age.[32] Thus, it is surprising to find this branch of conversation on aesthetics still being perpetuated by critics such as Roger Scruton[33] and Yael Reisner.[34] In general, it could be stated that the meaning of the term aesthetic has become synonomous with something whose appearance displays a particular set of qualities that evoke a response in the observer. The cognitive activity of aesthetic observations is a priori an exercise that is both perceptual as well as emotional. Considering this, it seems evident how this activity is profoundly connected to epistemological considerations. To stay with the example of theater in Vienna, the highly critical theater audience in Vienna “knows” a thing or two about theater and are not shy to classify the play as “good” or “bad” (at times, it is not so much about the content of the play but rather the quality of the performance). Theater critics are highly respected. Emotions can go high at the end of a premiere with a mixture of applause and booing (after the premiere of Thomas Bernhard’s “Heldenplatz” at the Burgtheater, I think I remember fists flying). In general, the belief that art can change the perception of the world is widely recognized, up to the point that good art can engender beliefs about the world and provide knowledge about it. The aesthetics of Neural Architecture is particularly interesting in that it allows us to reflect on aspects of human and artificial ingenuity, the position of architecture after several millenia of history, and its further development in a posthuman era: an aesthetic that oscillates between the familiar and moments of estrangement in an architecture that is at the same time alien but full of recognizable features.

[Fig. 13] Examples of the several thousand satellite images scraped from the internet to create a "terrain" dataset. This was the basis for the pattern of material (rocks, sand, gravel, earth) distribution in the Robot Garden. This is the basis of an esthetic consideration in the frame of neural networks © Image: SPAN

When I talk about the term sensibility, it is specifically geared towards aspects of artistic sensibility. In the previous section, I outlined a historical and theoretical development along the lines of Baumgarten’s and Kant’s definitions of aesthetics, which concluded with the insight that aesthetics is, at its very core, a theory of sensibility—evoking a response in the observer. This assertion discusses the arts of the past as much as the arts of the present, recognizing the aesthetic value as a specific feature of all experience. Or, as Arnold Berleant put it: “Such a generalized aesthetic enables us to recognize the presence of a pervasive aesthetic aspect in every experience, whether uplifting or demeaning, exalting or brutal. It makes the constant expansion of the range of architectural and of aesthetic experience both plausible and comprehensible.”[35] How is it possible to scrutinize the term sensibility in this frame of thinking? What I mean by sensibility is the perceptual awareness developed and guided through training and exercise. To this extent, it is certainly more than simple sensual perception, and closer to something like a guided or educated sensation. An education that has to be continuously fostered, polished and extended, through encounters and activities, to maintain the ability to execute tasks with an aesthetic sensibility. This ability is attributed in the Western traditions primarily to the arts—to painting, sculpture, music, literature, and so on—with architecture being this strange animal living somewhere between engineering and the arts. We can interrogate these territories of human production regarding their fashions, styles, etiquettes, and changing behavioral patterns resulting from transforming sensibilities. These territories and interrogations give rise to novel movements, and entire epochs, in the arts in general—and architecture in particular.

Agency in Neural Architecture

In the Western philosophical tradition, causal chains do not produce our choices, as would be the case with objects responding to natural forces, thus giving us agency. Free will and agency are closely related but not identical. Like cousins of the same family, they share traits in that agency is undetermined and significantly free. In contrast to inanimate objects, humans can make decisions and enforce them onto the world—for the moment; we will leave out the metaphysical question as to how humans make decisions. In any case, it entails moments of moral agency, as particular acts of human agency need thought and consideration about the outcomes. For this article, we rely on agency as part of the debate on action theory.[36] For example, this can be exemplified with the philosophical traditions established by Hegel[37] and Marx[38] that collectively consider human agency. Thus, we consider the relationship between humans and neural networks as a collective with a shared agency for our frame of thinking. In particular, we focus on the argument about ideas of materialism and realism, which we will unpack in more detail.

[Fig. 14] SPAN, untitled, 2019. The strange sensibility of the Robot Garden emerges from the collision of top-down design decisions and the bottom-up information provided by a neural network. An example of shared agency © Image: Levi Hutmacher

Neural Architecture is a New Paradigm

New paradigms have the habit of emerging when the existing paradigm has run its course—posing the question, what is the current paradigm? We will leave that larger question open for now, instead focusing on what Neural Architecture brings to the table regarding a substantial innovation in the architecture discipline. For one, it critically interrogates the role of the architect in the creative process of architectural design. Neural Architecture embraces the possibility of design methods that are deeply informed by existing information in the form of databases, and understands that the artificial modeling of neural processes can aid in harnessing the information in big data [Fig. 13]. Interestingly, the results do not resemble historical examples, and thus the methodology is not a repetition of Postmodern tropes, such as collage, quotes, and ironic assemblies. The results instead construct a frame around aspects of defamiliarization and estrangement in that we can recognize certain features without them being a copy [Fig. 14 & 15]. We are still at the beginning of this new paradigm of architectural production; the first built examples are currently emerging.[39] Many specific problems need to be solved, such as the relationship between interior and exterior, as neural networks based on images can only solve one of the two at a time. Or the problem of utilizing 3D models in this paradigm. Solutions are under development as these lines are written, and I look forward to how this new paradigm will impact the built environment in the upcoming years.

Figure 15. Matias del Campo & Sandra Manninger, Robot Garden, 2020 © (Image: Matias del Campo).