In 2020, President Donald J. Trump declared that the cement industry was an emergency industry. This new labor category took center stage in the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic to recognize professionals most exposed to the virus, including medics, teachers, mail, police, and grocery workers, among others. While workers who delivered food, taught and cared for children, and nursed people back to health obviously fit the category of emergency workers, cement laborers were a more surprising addition. After all, how—and why—is cement an emergency material? What does this categorization say about how we measure economic vitality using construction metrics? Why—and how—do we erect buildings in the midst of a global economic slowdown and health crisis? Who are the workers that continued to labor among dust, humming machine sounds, and virulent particles that the rest of us escaped from into the (dis)comfort of our laptop screens?

The Lehigh Valley is a cement manufacturing region in eastern Pennsylvania that gave rise to the US cement industry in the second half of the nineteenth century. Cement plants quickly became not merely local businesses that provided employment to entire family networks, but also shaped life from the cradle to the grave. Valley residents lived in a contradiction that is all too common for mining communities: on the one hand, workers complained about poor air quality, but on the other, they rejoiced when they saw dust in the air because it meant the plant was churning out the so-called “grey gold.” Workers remember seeing the cement plants from anywhere in the town—they were silent yet omnipresent actors in the drama and politics of everyday life.

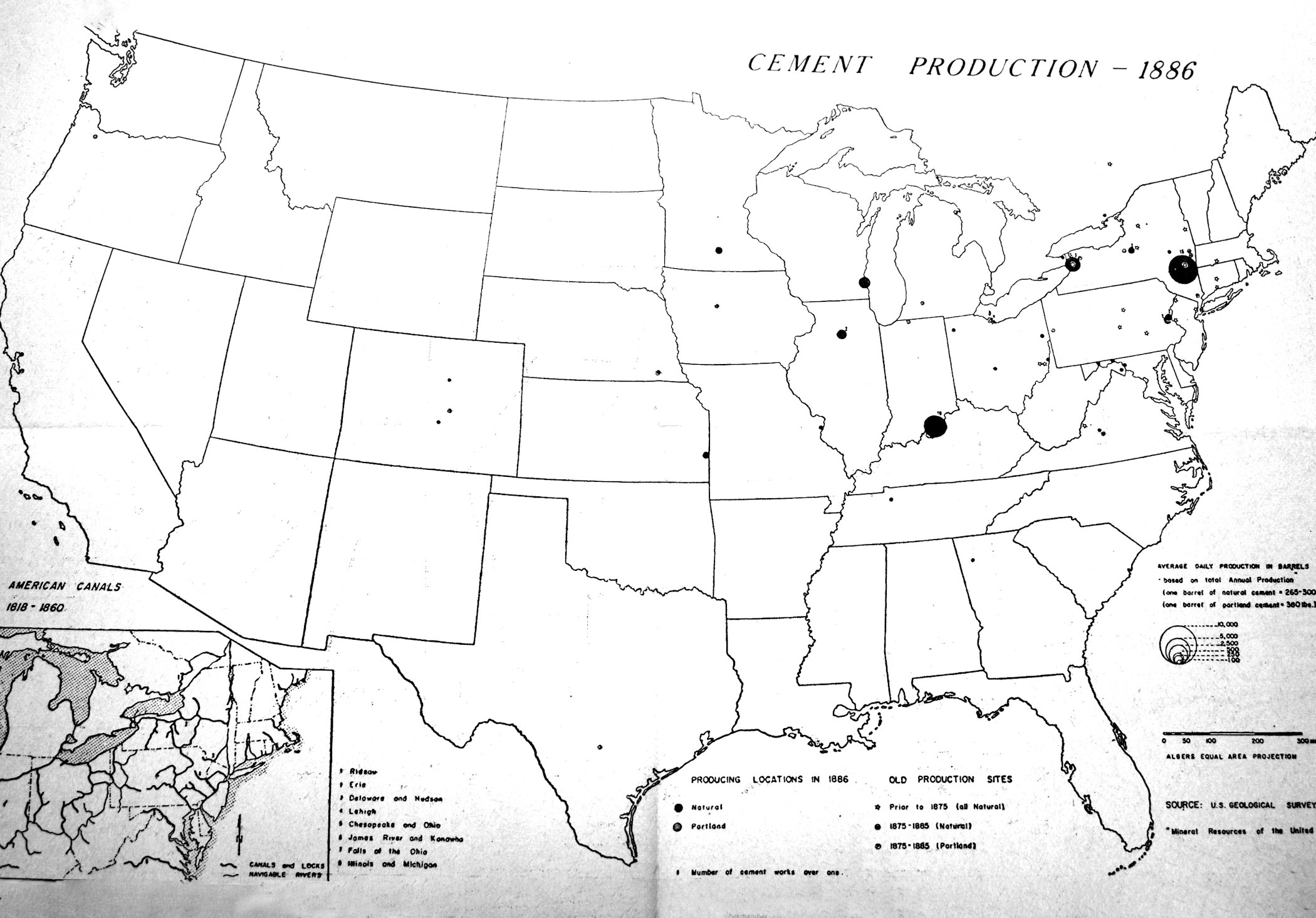

[Fig. 1] Cement production in the 1880s, largely concentrated in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania. During this period, the region made nearly 70 percent of the nation’s cement supply and it continues to be one of the densest cement manufacturing regions in the country. Map by US Geological Survey, 1886, Portland Cement Association.

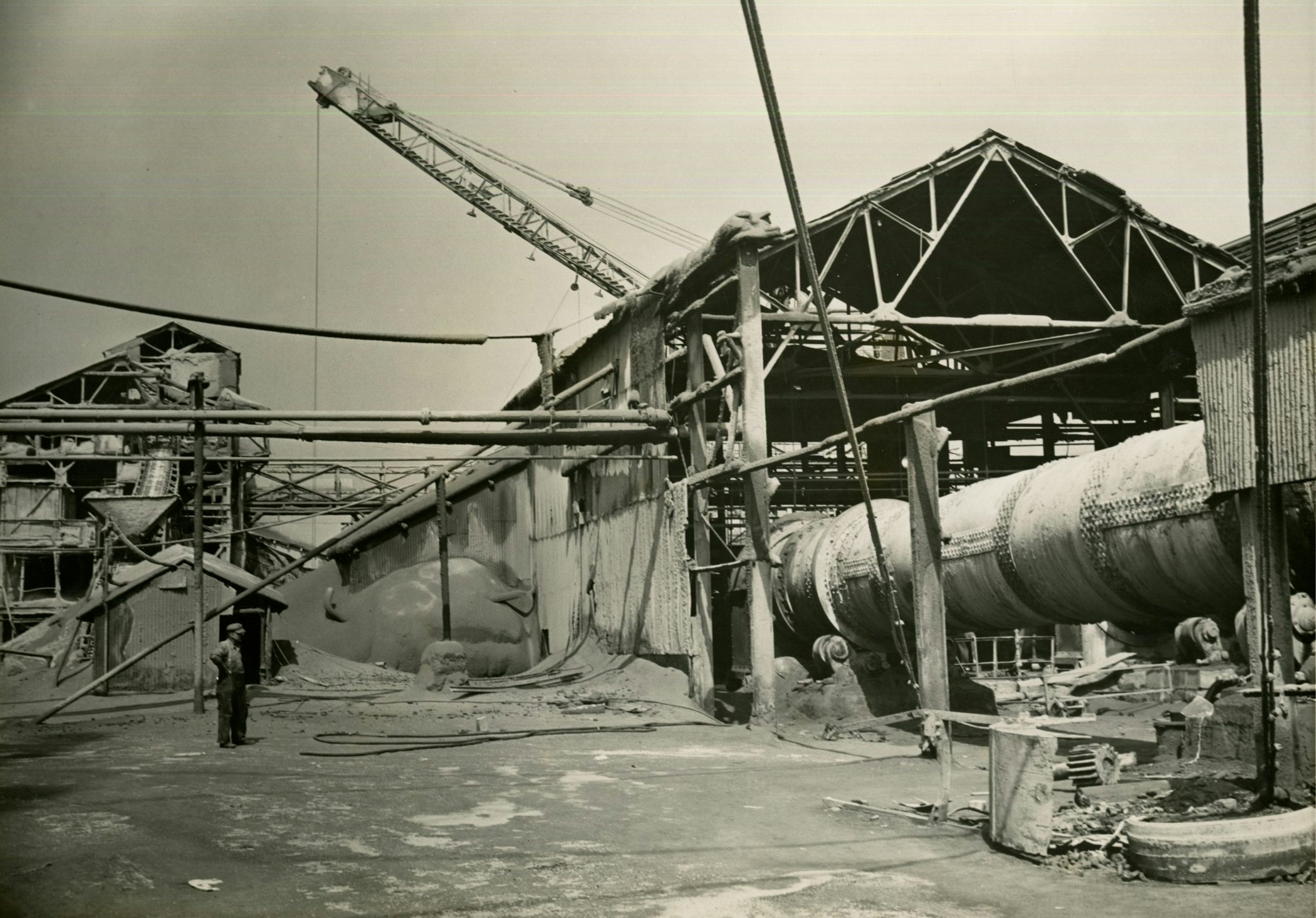

[Fig. 2] Thomas Edison, best known as the inventor of the electric light bulb, was a major cement manufacturer in the Lehigh Valley region. His development of the horizontal rotating kiln transformed cement manufacturing by significantly increasing capacity and output. Photograph of Edison’s plant, ca. 1920s. Thomas Edison National Historical Site.

INTERVIEW RECORDING: Lisa Wilcox interviewed by Vyta Pivo, 2021, Library of Congress

- Lisa Wilcox

-

There were I think—when I was a kid, there were, like, I think that the max was like 21 cement plants in the Lehigh Valley. So it was huge because there’s a vein of limestone. You can see it on a map of the United States, and it runs along the eastern states and you can follow them—if you had pins on where all the cement plants, they were right along that vein.

Some areas it’s actually a perfect match to make cement. You don’t have to add anything. Here we add both the iron and the sand to the limestone to make what they call clinker, which is then ground to make the cement.

Cement begins not at the awe-inspiring plant, but at the understated quarry. Typically located a mile or so away to utilize the locally available limestone deposits, quarries are large excavation sites easily identifiable by their distinctive terraces created as part of the rock removal process. Historically, workers employed chisels, hammers, and brute muscle strength to remove the rock, and horses to bring it up to the surface. Eventually, cement industrialists replaced hand-held tools with dynamite and horses with conveyor belt systems for greater efficiency. And since quarrying limestone was an expensive, dangerous, and labor-intensive process, businessmen often abandoned quarries upon running into challenges, like depths that were simply uneconomical to extract from. The abandoned quarries quickly filled up with groundwater and blended into the landscape as industrial lakes.

Ed Pany interviewed by Vyta Pivo, 2021, Library of Congress

- Ed Pany

-

Horses were used in the quarry to pull out the stone, used to take the dynamite in the stone into the quarry, used to haul the cinders from the boiler houses to dumps outside of the plant.

So the horses had names: Elias, Gabriel, most of them were named Saintly Horses! And we actually had eight farms and we had men whose job was only to take care of horses. And we had farmers here because we needed grain, we needed corn, they needed care. Some say the horses were taken better care of than some people took care of their family!

The kiln is the most expensive equipment in the plant that must run 24 hours a day. Workers occupy the central control room, which combines new and old technologies to monitor the complete chain of cement manufacture, from the performance of conveyor belts, feeding and crushing machines, to the burning temperature inside the kiln. Over time, workers become proficient at anticipating technological challenges and intuitively responding to the needs and character quirks of different technologies. In some cases, workers acquire machine-level accuracy themselves. For example, some workers attend the so-called smoke school that teaches them how to visually spot unacceptable levels of dust in the air. Cement workers often describe their relationship to the machines through a language of care, referring to themselves as babysitters or caretakers.

Matt McCullough interviewed by Vyta Pivo, 2021, Library of Congress

- Matt McCullough

-

A good example that I tell some of the newer guys that I've trained out back in the past where the feed end is—take for instance, dustbin two and dustbin one. Dustbin two always has trouble feeding as opposed to dustbin one. Sometimes you forget about it because it feeds all by itself all the time.

But dustbin one can be a little bit more temperamental, I guess you could say. So yeah, with something like that, I’d rather... I’ve already said it, that baghouse one, which is pretty much the dust collector for kiln one always behaves better than than baghouse two. So it's funny. It's funny that that’s how I say it, but everyone who worked back there knows what I’m talking about. So it’s funny in that way.

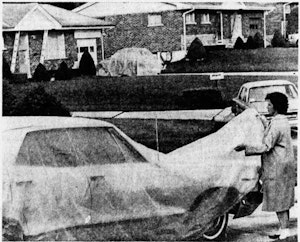

The cement plant is a uniquely dusty environment—stepping foot in it is like putting on gray-tinted glasses because everything, from personal belongings to floors and buildings, becomes covered in this gray powder. To mediate this issue, companies provide showers and a cleaning service to ensure that workers do not bring cement dust home. But since the gray matter passes through a sieve that water cannot pass, cement dust not only travels home, but also invades the interiors of workers’ bodies. And it is the job of women, and most often women of color, to contain and manage the ill effects of dust.

[Fig. 3] Americans living near cement plants had to come up with clever ways of protecting their property from cement dust, including covering their cars with plastic tarp. Photograph published in Jacob H. Wolf, “Cement Dust Pollution Stirs Affton Area,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 6, 1969.

Phil Gheller interviewed by Vyta Pivo, 2021, Library of Congress

- Phil Gheller

-

Masks–and a lot of times a lot of us will wear masks, and especially in the Labor Department when we're air lancing or jackhammering stuff when there's a lot of dust in an area. Normally I suggest to the newer guys, put a mask on. You don't want to blow in, to suck all this dust in. It's no good.

- Vyta Pivo

-

Yeah, can you feel it after some time?

- PG

-

Oh, yeah. Yeah. Yeah, you feel it. And it's it's strange because you can tell– you can feel the difference in the– so, like, the stone dirt's not that bad. And then so the stone gets ground up into our– it's what we call raw dirt. That's not so bad, but then when it gets through the kiln then it's made to clinker. That dust hurts. Like, you can actually feel the difference.

- VP

-

How do you mean it hurts?

- PG

-

Well, it's kind of gross. It gets built up in your nose and, like, you feel it kind of in your lungs. You can feel a little bit of the…not really sure, I’d call it a burn, I guess. So I am always wearing a mask around clinker. I learned that pretty quick. And clinker dust, if it gets on your skin, especially in the summertime when you're sweating, it'll burn your skin a little bit. Irritates your skin. Yeah, we have stuff the company supplies creams to put on, and it does work. Like a skin shield. Foam that we can put on.

- VP

-

Before going out to the–? Oh wow, I had not heard of it.

- PG

-

Yep. Yeah, it works.

- VP

-

Do workers use it, or not so much?

- PG

-

I feel like some of us do. It's just a personal choice, I guess, if you don't. But I've noticed– if you're sweating and you get that on you, you're going to get some type of irritation.

Even though work at the cement plant is difficult and dangerous, men and women continue to labor in the industry because the strong union infrastructure ensures pay protections and good healthcare. Mike Sterner, a cement worker and union vice president, works long regular shifts at the plant and then takes on his service role to ensure that workers are treated fairly. As Amazon, FedEx, and other warehousing and distribution companies encroach upon the Valley for business, in turn increasing demand and competition for unskilled laborers, cement plants are confident that they will win out. Especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, good healthcare, even if it comes at a price, is worth the tradeoffs.

Mike Sterner interviewed by Vyta Pivo, 2021, Library of Congress

- Mike Sterner

-

Well the biggest one right now, and not really post-pandemic because it was before the pandemic also, is usually health insurance. Because that's a major cost for the employer.

So it's always—they’re trying to cut their costs because of– they don’t want to raise the price of their material. We don’t want to have to pay outrageous bills either. So I think that relates to every industry across the board the United States right now—health insurance, that is one of the huge ones. That, and I think also we’re going to be facing the right to work thing that’s going on.

Learning from the Lehigh Valley cement workers offers a perspective that is not rooted in design directly, but one that helps us to understand how design and construction shape the labor of materials manufacture. Through the case of cement workers, we can grasp the linkages between urban growth and quarry lakes, low costs of concrete and limited health protections for workers. Perhaps only when cement workers are labeled as emergency workers, we can ourselves emerge with a better sense of why we build, and with what.

For more information and the full set of interviews with Lehigh Valley cement workers, see “Cement Workers in Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley.”

The interviews were supported by the Archie Green Fellowship for Occupational History, Library of Congress.