Interview recorded on January 19, 2023. Cyrus was at the Taubman College Liberty Research Annex located next to the Ann Arbor Railroad, a partially revived freight line that once used to transport goods from Toledo, Ohio to Elberta, Michigan. Ersela and Stephen were at the Texas Tech University College of Architecture located within El Paso Union Depot, an active train station served by Amtrak’s Texas Eagle and Sunset Limited lines.

- Cyrus Peñarroyo (CP)

-

Hi, Ersela and Stephen! I'm excited to speak with you today. I'd like to start by asking you to reflect on the place in which you currently live and work. Your firm AGENCY is based in the border metropolis of El Paso-Ciudad Juárez, and much of your research and design investigations have focused on the environmental and political challenges that span across this borderland region. You've also worked on a range of projects in other parts of the world—for example, Italy, Albania, and Hong Kong, to name a few. What drew you to this part of North America?

- Ersela Kripa (EK)

-

It's sort of serendipitous. We were finishing the research for our book, Fronts: Military Urbanisms and the Developing World, and traveling through the American Southwest with graduate students from Washington University in St. Louis to look at extraction sites, military training environments, and other issues of specific scarcity as they intersected with the border condition. We gathered so much information during this seven-day trip and felt that this context would help us to “groundtruth” our research, and that our work would become grittier if we lived within the context we were researching.

Luckily, Texas Tech University was also growing their site in El Paso. We were both able to relocate through that hiring process and have been here now for seven and a half years. Since then, the research for the book became much sharper since we could visit all the sites that we wanted to include in the publication. Simultaneously, we produced journalistic photo essays for The Architect’s Newspaper that stemmed from our experiences living here and being within walking distance to the border. We were able to read national news, then walk over to locations mentioned and document for ourselves what was truly happening.

- CP

-

And how would you describe the role that infrastructure plays in your own understanding of the US-Mexico border? Or, to rephrase that question, what has “thinking infrastructurally” allowed you to notice about this specific region that other perspectives have maybe overlooked? I think about, for instance, the persistent narrative around “national security” at the border, but when I look at your work you seem to deliberately resist this narrative.

- Stephen Mueller (SM)

-

The region could really be defined infrastructurally in so many ways beyond just the border wall. We’re at a crossroads, especially if you look at transcontinental rail travel north-to-south through all of Mexico and east-to-west through all of the US. People think that El Paso is in the middle of nowhere but it’s sort of in the middle of everywhere—it’s literally at the intersection of huge logistics networks, with the rail being just one example. We’re a lot more interested in the infrastructures crossing, spanning, or blurring the international boundary because these are the ones that really sustain the economy and culture particular to this region and will, therefore, need to receive more design energy in the future. The borderland is super dynamic and changing all the time, which not only puts a lot of stress on existing networks but opens up opportunities to reconceive or rewire some of these systems so that they’re more equitable, just, or forward-thinking in how they confront the problems of the region in the coming years. Maybe this is tying back to your first question but we’re drawn to this place not only for the challenges it presents but also because there’s a substantial legacy of connection that can be built on.

[Fig. 1] A moment along the Rio Grande River where the Great American Dam meets the border wall © AGENCY

- EK

-

There’s an amazing location where we always take people from out of town and where we sometimes situate our studio courses. I’m referring to where the Great American Dam was built in 1935 as part of the 1906 treaty between the US and Mexico to calculate water distribution of the Rio Grande, imposing infrastructure on an otherwise wild river with its own natural flows [Fig. 1]. Today, this particular location has factories on both sides of the border producing bricks from local materials, and these bricks make their way through the NAFTA logistical network. Also crossing this area is the railroad, which takes objects that have been assembled in Juárez, in the free economic zone (FEZ), and moves them into the US where they are distributed to ports along the East and West Coasts and globally. All this to say that there are scales and layers of physical infrastructure that have shaped and reshaped this territory in fundamental ways over time—these infrastructures are felt, we see them everyday when we drive to work, and they’re just unavoidable.

With regards to the border wall, it’s not really an issue here because local communities on both sides continue to cross everyday for work, including some of our own students who cross to study. The El Paso-Ciudad Juárez Metroplex is connected through its own “frequent traveler” cards, making this daily commute much easier. There are even binational deals on tuition, which means that students who live within a certain mileage of the border don’t pay international fees. Despite this region being incredibly fluid, the conversation about the border wall becomes ossified nationally at the centers of political governance, which affects people who are on the move from Central and Latin America. Further south or north is where the wall is this “thing,” an imaginary but also real obstacle, but the situation is not really different here on the ground.

- CP

-

It seems like such an exciting context to inhabit and work within. I’m really interested in how specificities of a place help you recast these expansive, almost universalizing infrastructures. For example, one might assume that water or electrical infrastructure functions in the same way regardless of location—simply put, these infrastructures supply water or electricity to people who need it—but really understanding how these systems are situated can reveal so many more issues that people are facing.

To get into this a bit more, how have the places in which you were raised—Ersela in Albania and Stephen in St. Louis, Missouri—influenced your work on borders, ecologies, and spaces of conflict? I ask because infrastructures certainly framed my own experiences in Kansas City: my family lived fifteen minutes away from an international airport, we took many road trips to Columbia or St. Louis via I-70, and I spent my teenage years hanging out in the Crossroads or West Bottoms amidst repurposed structures that once served the country’s railroad enterprise. As an adult, I even witnessed the first deployment of Google Fiber across the metropolitan area. I sometimes wonder if being more attuned to systems that connect people and places has contributed to current fascinations with internet infrastructure in my own research and creative practice. Stephen, I imagine that the presence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, the interstate highway system, and the history of social and spatial injustice throughout St. Louis may have shaped your worldview. Do either of you see links between your early experiences with infrastructure and your approach to infrastructure today?

- EK

-

Well, I grew up in a Communist dictatorship, and I was one of the refugees who crossed the border after the Communist system failed. So, the specific way my brother and I experienced the border in Gjirokaster, Albania was motivated by our own safety: we needed to cross it and we weren’t going to wait for someone to say it’s legal, allowed, or whatever. Maybe because I was also very young—I was a teenager, and when you’re a teenager you don’t really feel the weight of the world like you do as an adult—but this kind of infrastructure appeared to be an obstacle though it wasn’t really limiting our ability to have a safe life. So, we crossed it.

As I see it, infrastructures are generally constructed by people in power, and people in power, especially in this country, have historically reinforced systemic racism and exclusion, often through spatial practices of militarized control. We don’t engage the border wall, and we’re not interested in projects that say we have to live with it. Instead, we work tangentially, around much larger issues that this kind of infrastructure has impacted and enabled, like environmental pollution or ecological and spatial neglect. We are figuring out ways to “work around” infrastructure, and this approach may be informed by those early years spent crossing a border.

- SM

-

Yeah, I appreciate the question, and I don’t know that I’ve ever really thought about this. I do think that the impact of the Mississippi River, not only as a conduit but as a border, was very much part of my understanding of place growing up. I remember doing this geography project in fifth grade—around the time when the major floods of the early nineties were decimating the Mississippi River Valley—and learning that the management of the floodplain was largely in the hands of the US Military, specifically the US Army Corps of Engineers, and even considering alternatives like restorative wetlands as a grade schooler. [laughs] So, I guess some of these attitudes have been with me for a long time, where I consider how an inherited legacy that might have been built under some national security agenda could be appropriated or reimagined in some way.

The “bordering” of St. Louis was also very much a part of my understanding of place. You know from Kansas City, and the distinction between KCK and KCMO, how the state border establishes different social and economic realities. There’s a real geographic border between St. Louis and East St. Louis, but there’s also a north-south division with the infamous Delmar Divide and all the impacts of redlining that were made clear in Ferguson but have always been part of the city. I suppose that my awareness of how spaces are bordered, either physically or otherwise, and my attempt to work across these conditions have always been a part of my attitude towards space.

- CP

-

Shifting from past experience to current practice, I’d like to ask about your process. You often begin a project by documenting or mapping existing conditions in order to uncover or make visible otherwise invisible forces. I understand that these visualizations allow you to advocate for vulnerable urban populations and that critical cartographies can inform calls to action. As you shift into developing spatio-material propositions that respond to contexts that you’ve observed, how do you make the jump from looking to acting, or from observation to design? For instance, you created a shade structure in response to health risks associated with ultraviolet (UV) exposure in the borderland, and it seems important that the structure not only responds to data you’ve collected but also communicates that information to a wider public as part of the experience.

- EK

-

Yeah, that’s always the most exciting part of any project.

When we first moved here, we had a sense that comfort in the desert and along the border is unevenly distributed across zip codes and in relation to income levels. This means that there are some neighborhoods on the west side that have amazing parks with trees and shade but areas in south and south central El Paso, against the border, where there isn’t as much coverage. However, we noticed that there’s a real lack of spatial data that could ground our observation and that there wasn’t a way to translate and connect data across the border. We couldn’t even find a digital model that correlated the two cities because the two nations measure and prioritize things differently. So, we not only had to find information, we also produced and designed our own data in order to have a base layer that could be shared with a public that might understand this condition as a lived experience but have never seen it mapped.

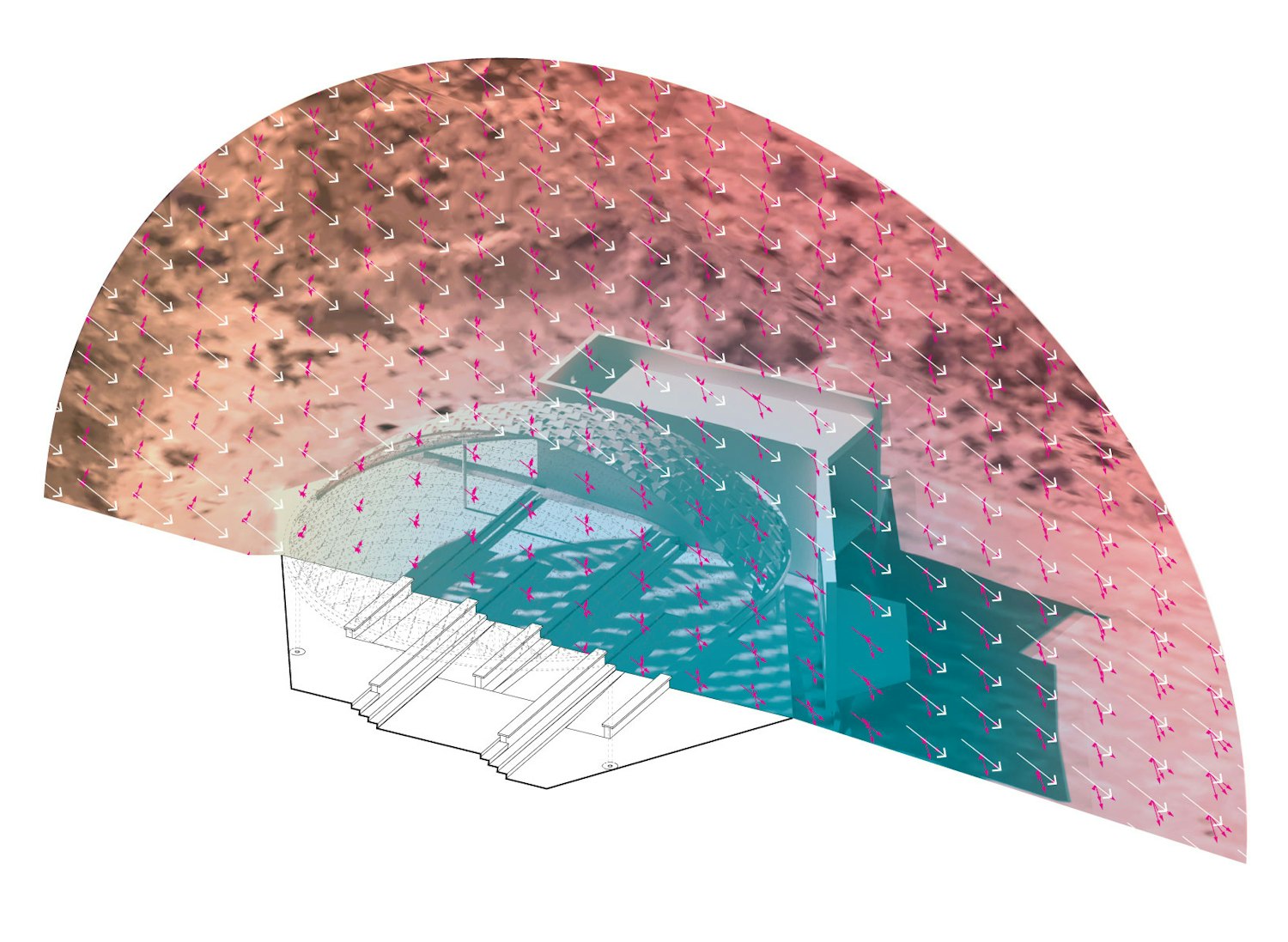

With all of our projects, there’s always that first moment where we say, “Okay, we feel this, and where do we find out how this really works?” So, we started developing our own workflows that began with a review of satellite data for UV exposure, ground temperature, and availability of shade. We then layered this information in ArcGIS and invented a Grasshopper definition that allowed for a block-level analysis of exposure [Fig. 2]. This allowed us to generate images showing the inequitable distribution of shade and protection against UV radiation that seems heightened around the border where migrants gather and where people wait for public transit. These diagrams also confirmed that conditions are a lot more comfortable as you move through more affluent neighborhoods.

[Fig. 2] Radiation Analysis for Safe Shade Classroom, El Paso, 2022 © POST–Project for Operative Spatial Technologies

- SM

-

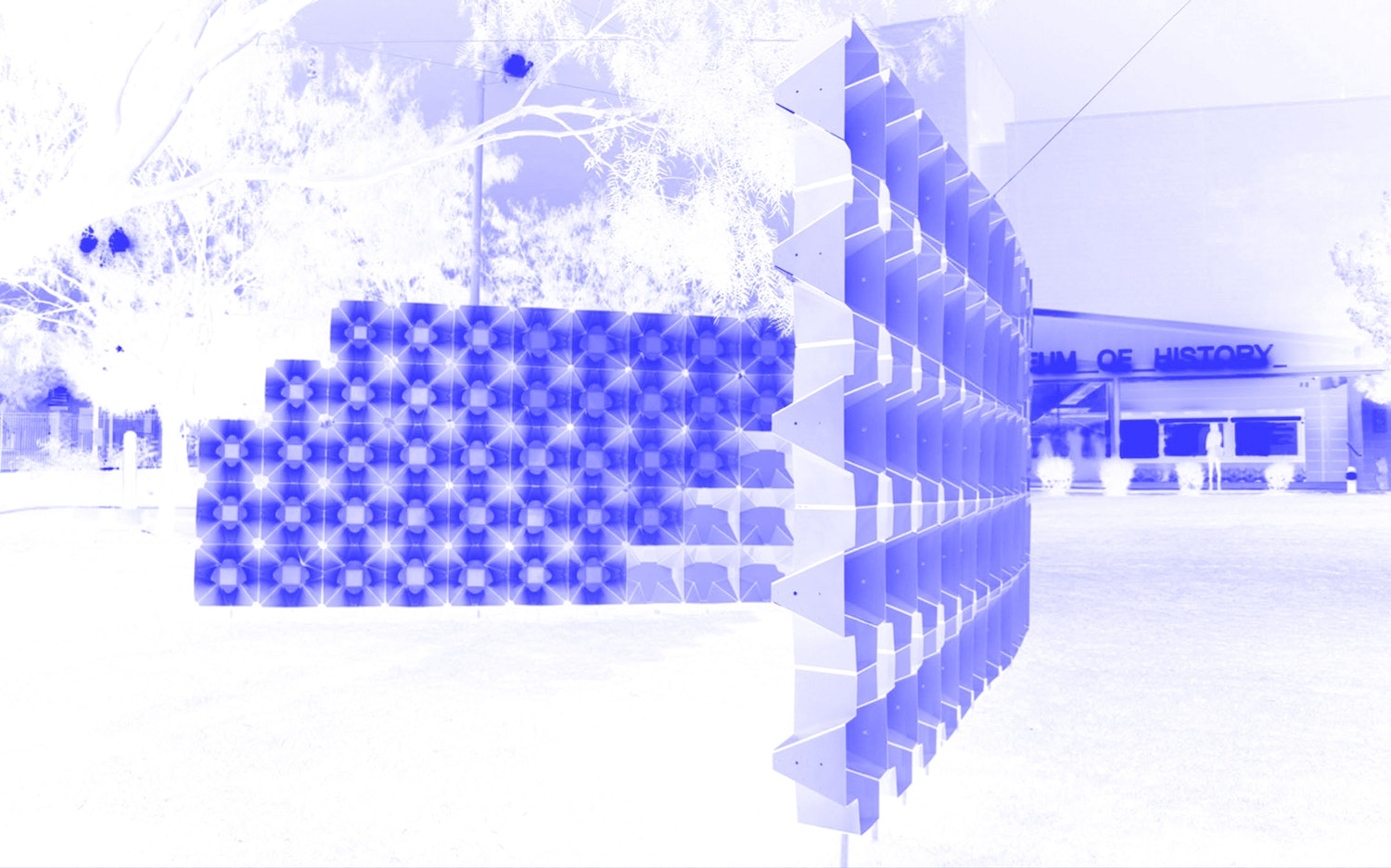

I think the engagement with data throughout our work is twofold: we can use data to help us design “informed objects,” and people can receive or inhabit data as part of the end result. In some ways, it’s very one-to-one, like the transmission of data in our project SELFIE WALL where an interactive display presents back to visitors their social media posts after they’ve had a chance to experience the installation [Fig. 3]. In the shade structure, we’re still working on what that form of engagement might be. Right now, it’s only at the level of encounter with the “informed object” and the spatialization of a new public that can gather and communicate certain things about the issues it embodies.

[Fig. 3] SELFIE WALL, El Paso, 2016 © AGENCY

- CP

-

Yeah, in projects like SELFIE WALL, or even your air quality monitors designed to track dust in the region [Fig. 4], access to data becomes a way for you to enroll participants in critical decision-making processes. So, for instance, asking oneself questions like, “Am I willing to share my facial data when I post a selfie online?” or “Is it safe to breathe the air around me?” seem central to the experience of the project. With respect to my own creative practice, I’m certainly inspired by your desire to challenge the “passive data consumer” to think differently about their surroundings. Could you say more about why building such critical awareness of infrastructure is important to your work? And is the somewhat immeasurable nature of “becoming aware” something you think about?

[Fig. 4] Custom air quality monitors housed inside of surveillance camera enclosures, El Paso, 2021 © AGENCY

- EK

-

With the dust monitoring project, we used really inexpensive DIY sensors that don’t necessarily present an accurate composition of particulate matter, but they do tell us the volume and size of particles. So, this data is by no means precise and citable for scientific papers but provides an impression of binational flows, areas of infrastructural or ecological neglect continuing to desertify and cause increased amounts of dust in the air, and origin sites. Using this data, we produced a drawing collaboratively, together with people on both sides of the border who agreed to host the sensors and share data, as a way to negate the conversation that happens here within local governments on both sides of the border. People in Juárez say, “All the dust is coming from El Paso, it’s not our problem, we can’t fix it,” and people in El Paso say, “All the dust is coming from Juárez because they’re not paving their roads.” So, we produced this swirl animation showing what the wind truly does, how dust is shared, and that we breathe it together regardless of which side of the border we live on. This is the conversation we want to have.

With SELFIE WALL, what’s really important for us is that…

[whistle from an incoming train interrupts the conversation]

…sorry, we’re in a train station.

- CP

-

[laughs] Coincidentally, I’m also next to a train line.

- EK

-

Awesome. [laughs] Our school and research center is in a functioning train station. So, a bit of hybrid infrastructure here…

But, for SELFIE WALL, it was important that people saw how quickly someone could catalog and geolocate them from digital data. We weren’t saying that that’s good or bad but that people should be aware of how their personal information can be used.

- SM

-

For projects where the impact is immeasurable, or where the impact is at the time scale of an event, conversation, or provocation that could have more longevity through publication, we know that the work is not as wide-reaching as we aspire for our practice. But by moving to El Paso and developing the slow work in tandem with quick deployments—in other words, working with local NGOs to do longer-term and maybe even permanent installations like the shade structure, or working with city governance and the planning community to develop projects that might last longer and reach larger audiences over time—there’s now more time for people to interact with our projects and experience the space of information, which also means there’s more time for us to evaluate, optimize, or improve the outcomes.

- CP

-

Yeah, it seems like your work thrives off of conflict or debate and that providing a venue for prolonged discussion is more fruitful than actually trying to change one’s digital habits. So, when you create these spaces where people have to decide for themselves and discuss with others their own attitudes around sharing facial data, or their cross-border impressions of who’s responsible for producing dust, perhaps the conversation is really the project.

- EK

-

Yeah, that sounds right.

- CP

-

Given the complexity of some of the issues you're taking on, how do you draw the line between your expertise as architects and the expertise of policymakers, planners, scientists, and others? And how would you articulate an approach to designing infrastructure—what does that entail?

- EK

-

That's a very good question, and it’s a question that directly relates to phases in one’s own career. We first had to gather and measure data, then produce data and try to understand how policy decisions around the desert might be shaped by our findings. Now as we propose design strategies, we’re actually talking to local city governance to find synergies and ways in which our expertise can really be part of their thinking. We’ve been meeting with the El Paso Office of Resilience and Sustainability, which is doing phenomenal work. They not only understand resilience on ecological terms but also financial and cultural, by which I mean they ensure that communities are still economically empowered and stable through their resilience-thinking. That’s just incredibly progressive and allows us to think on multiple scales of infrastructure design.

Returning to this idea of shade in the desert, shade is so important for health reasons, especially with children. Children usually play outside during the summer when they're off from school, but here that's not always possible because it's so hot, which has led to issues of obesity and early-onset diabetes in younger people because they just can't be outside. These are things that we, as architects, don’t necessarily think about, but there are domino effects that our work can engage through the specific steps of policy, which I think is really exciting. So, we’ve been collaborating with Insights El Paso, a nonprofit science organization committed to education, to design a shade structure that will make it possible for them to prolong their teaching and hold classes during the summer. Though this one-off outdoor space is a small-scale intervention, it becomes infrastructural if we couple it with large-scale analysis.

- SM

-

I think we see ourselves, and maybe architects in general, as having the ability to create a situated experience from complexity, or an experience that doesn’t try to reduce the messy entanglements of complex issues. Sometimes we create these situated experiences in the research by putting a finger on key locations or leverage points that could illustrate and potentially transform existing conditions—we identify the major concerns, locate areas where we can work on them, and work with people on the ground—and sometimes we create these experiences through design. I think we’re happiest when the thing that we make contains or alludes to the complexity but is also digestible. In other words, it shouldn’t take a 400-page book to explain what you confront as you’re inside the installation or space that we’ve designed.

Additionally, we often work with people from other disciplines, like geologists, environmental scientists, or urban planners, and it’s rewarding when they begin to see their own contributions in a new light after seeing how we interpret their work from our perspective.

- CP

-

This brings me to my next question. You often work between counter-mapping exercises that span vast territories and multimedia environments that distill larger issues into smaller inhabitable spaces or structures, and you seem to skip over the “building scale” in a way that seems advantageous to your practice. Could you talk about some of the opportunities and challenges that arise from moving across these two scales, from large territories to small installations?

- SM

-

It’s disorienting. [laughs]

- EK

-

We don’t really have a project that focuses on one scale. Maybe because when we started our practice after receiving the Rome Prize in 2010, we were simultaneously conducting research for a book and developing infrastructural ideas through design, so we aren’t avoiding the building scale intentionally but it just doesn’t seem to fit within the trajectory of our practice. We do have building projects in AGENCY that we’re currently working on, but the time scale of the academic calendar seems to favor research, writing, digital information, and quick installations.

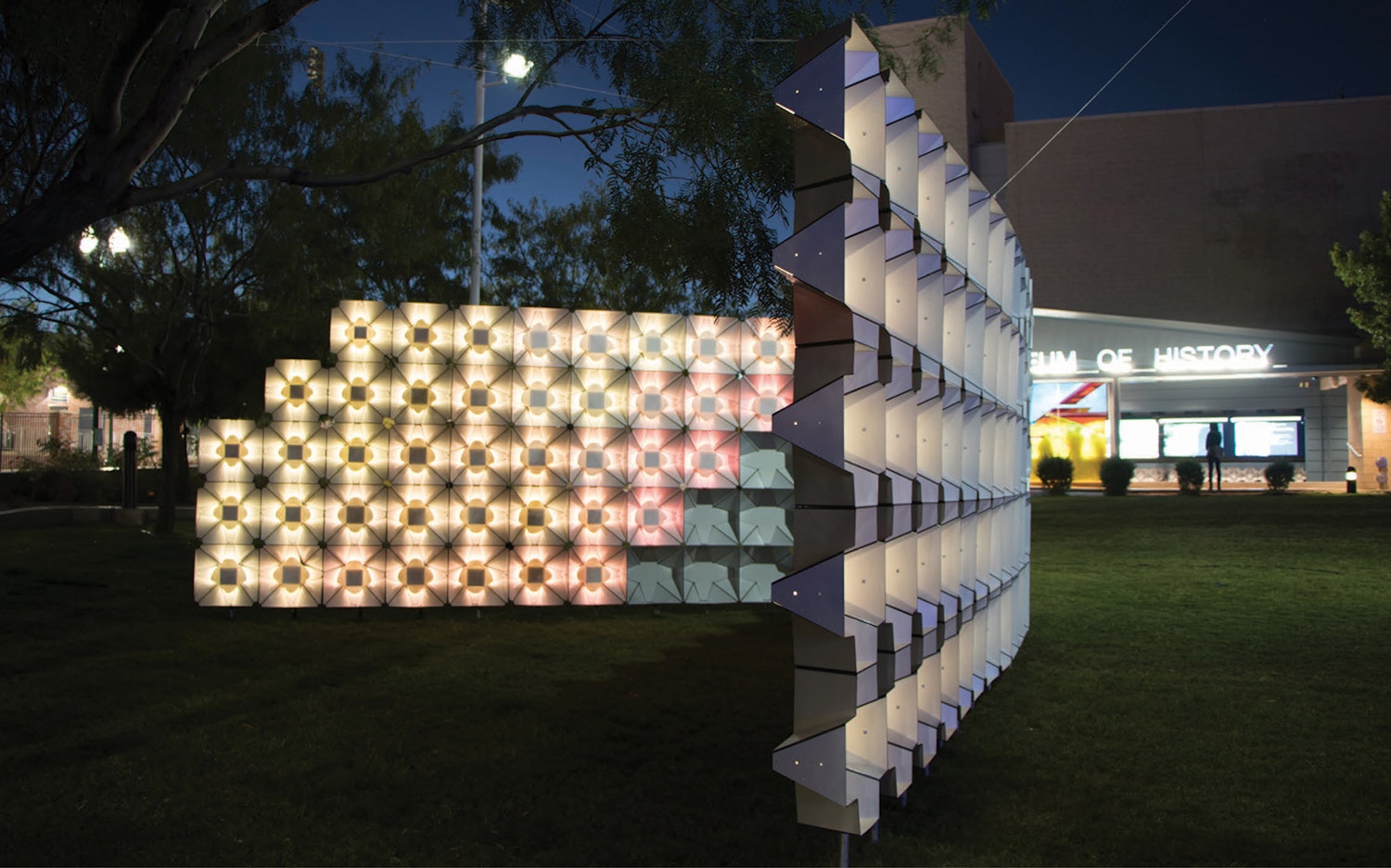

Related to this issue of scale, we design our installations, like SPECTRAL for Exhibit Columbus [Fig. 5], so that the two of us can install them ourselves if we can’t find others to help us. We do the work on the machining end in a way that’s foolproof for construction, and it’s rewarding to know that our unskilled labor can put something together that needs absolute precision. I don’t think we could do this at the scale of a building, you know? We like being able to fully understand the steps and scales of our projects, whereas buildings require thinking for contractual and multi-team execution that might not necessarily be in service of the research.

[Fig. 5] SPECTRAL, Columbus, 2021 © AGENCY

- SM

-

Maybe just to add to that, I think one of the advantages on both the research side and building side is that there’s an attitude to make things radically public, open, or accessible. It’s not that we’re turning down building commissions, but I think interventions within public space allow for more direct engagement with the kinds of publics that we want to encounter, inform, and learn from in the work. And that gets more and more difficult when you enclose a project in a cloak of private ownership. The scale of public building really excites us and is where part of the practice is devoting some energy. I think you hit on something there, that the desire for the work to reach a certain audience might not be met in a singular envelope.

- CP

-

Yeah, I’m struck by your earlier use of the word “disorienting” because I can imagine that when it comes to designing infrastructures, creating a smaller scale intervention is a way to better understand specific relations of power in one moment instead of trying to address the entire system. I get the sense that these installations allow you to bracket infrastructures in particular ways so you can work on them in a manner that’s less disorienting.

- EK

-

Yeah, that’s right, it’s almost like a proof-of-concept model.

- CP

-

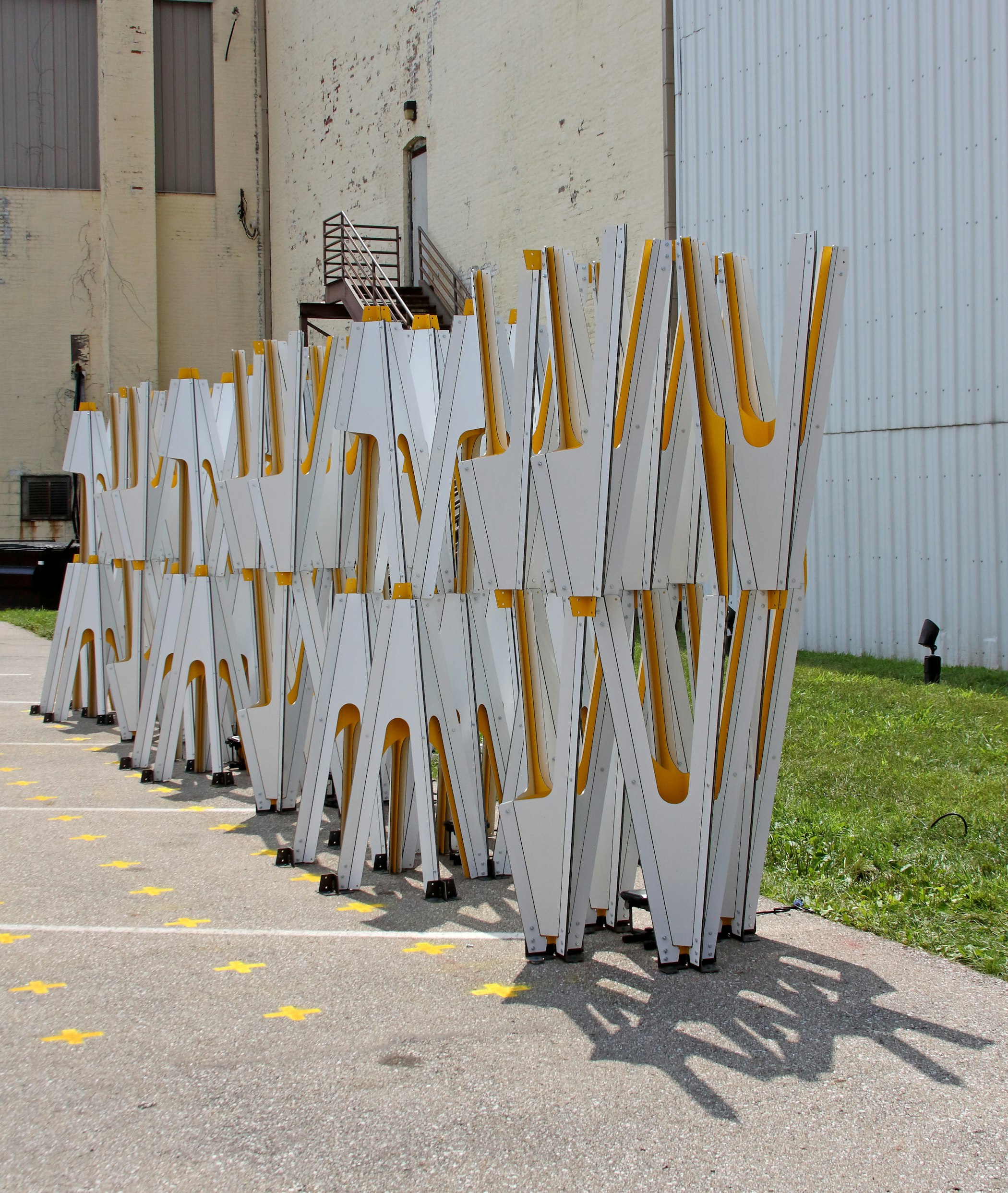

Shifting to another aspect of your work…In our editorial introduction for this issue of Gradient, we raise the question “whose infrastructures?” Related to this, you seem to be “hacking” infrastructures in many of your projects, in an effort to support marginalized communities impacted by these systems. In a way, hacking becomes a way of re-socializing infrastructure so it functions differently than intended. I think about your canopy installation that temporarily decommissioned orange traffic barrels typically rented by the Department of Transportation for border patrol purposes; your rebranding of dumpsters in Albania to encourage safer access to recyclables; and your reuse of surveillance camera enclosures to house dust-monitoring sensors, which we discussed earlier, just to name a few examples. Could you talk about the significance of hacking to your practice?

[Fig. 6] Remix, Tirana, 2012 © AGENCY

- EK

-

Yeah, I think infrastructure should be multi-functional and multi-scalar so it can open itself up to specific and increasing climate disasters, resource scarcity, and human migration as a result of climate change. It seems that thinking of infrastructure in a very modernist way—that it serves one purpose—no longer makes sense, and maybe never really made sense. So, hacking for us was a way to think about what constituencies are not served by specific infrastructures and how they could become part of a support system that was inherently not designed for them.

The rebranding of the waste receptacles in Albania, where we spend our summers, really started with us seeing that there’s an entire population (specifically the Roma population) who uses their hands to recycle, rummaging through organic matter and waste in order to find bottles and other recyclables. This is the informal economy around recycling in Albania. We asked ourselves, “How can we make their workday easier so that they’re not unhygienically using their hands to touch other people’s waste?” There are many renditions of this project, but in one version we decided that if we can make it fun and color-coded, people may alter their behaviors and self-sort waste before it’s sifted through by recyclers [Fig. 6]. For us, the question is always, “Who does this infrastructure exclude?” and we then try to identify the tiny valve or button you can press to greatly impact how a specific community makes a living or deals with larger ecological consequences.

I think that’s the philosophy for all our projects, that there’s an enormous topic we’re thinking through and then the design project is always a tiny object we can guerilla-install somewhere, and that object might have a much larger application.

- SM

-

Yeah, I think there’s maybe two moments of the “hack” that we think about. One moment considers legacy infrastructure that might already be in place and how to transition it to a new use; or how to help people reach new kinds of understandings, like with the sensors embedded within surveillance camera casings. Another moment preemptively hacks by looking at the ways in which infrastructure is being invested in so we can promote next generation infrastructures. We think about how to build certain capacities into these systems, like having multiple uses or serving under-advantaged communities. In our practice, we think design can serve both roles: we can transform the existing and we can transform future attitudes towards infrastructure.

- CP

-

This is a great note to end on, this notion of hacking both the present and the future, because it reminds us that infrastructures are situated in place and time. Infrastructural design certainly involves responding to numerous social, political, and economic factors, but its transformative potential lies in its ability to offer another way forward, or alternative ways to be in relation with one another. Thanks, Ersela and Stephen, for sharing your work and process with Gradient!